Our stories serve as a record of what we did on a given day and often describe what we felt at the time. They help us trace the intersecting lines that have brought us to the present. Our stories are the vivid presentation of our history, but all good stories connect us to another. When someone tells us his story, we walk with him through his landscapes and with him see all those people he captures with his voice. What follows are stories about Alma and Earle Vogels, my in-laws, survivors of the Depression and World War II, husband and wife of 64 years.

Alma attended junior high school during WW II in the Pennsauken schools. She remembers one winter when coal, diverted primarily toward the war effort, was so scarce that the schools were closed from late December to the beginning of February. She and her mother and brother came out of New Jersey and up to Green Lane to an unheated, rural summer cottage. She ice-skated on the Unami Creek, read, played games and sledded down the hill to Wetzel’s bridge.

Unami Creek in Green Lane

They kept a kerosene heater in the kitchen. Ice formed on the inside of the bedroom windows. They walked outside to use the outhouse and to pump their water.

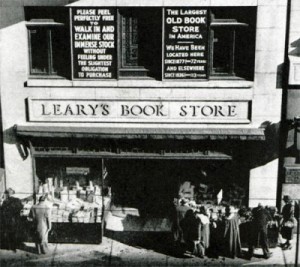

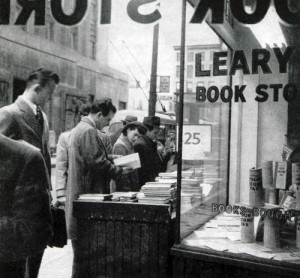

Her father, Newlin Hoagland Harter, drove up every weekend. Alma remembers watching him pull cartons of books out of the backseat, shouldering them and walking toward the house while they watched, thrilled at what might be inside those boxes. He bought them for .50 cents a box at Leary’s, behind the old Gimbals’ Store, three stories filled with old books.

Her father, Newlin Hoagland Harter, drove up every weekend. Alma remembers watching him pull cartons of books out of the backseat, shouldering them and walking toward the house while they watched, thrilled at what might be inside those boxes. He bought them for .50 cents a box at Leary’s, behind the old Gimbals’ Store, three stories filled with old books.

Together, she and her mother would scatter the books on the table and separate them according to topic and their interest. She grew to love Dickens then and still fondly remembers reading A Tale of Two Cities for the first time.

During this same time, Earle was called up in the draft. When he appeared in front of the Board, he could have chosen the Army, Navy or Marines. He  chose the Navy. He thought the Navy would be cleaner. He did not want to “roll around in the mud.” He knew what the Marines were doing in the South Pacific. He did not want any part of that. Instead he was trained to repair portable and desk set radios.

chose the Navy. He thought the Navy would be cleaner. He did not want to “roll around in the mud.” He knew what the Marines were doing in the South Pacific. He did not want any part of that. Instead he was trained to repair portable and desk set radios.

He was the only one of one of his classes not to earn a high enough grade to go to a specific school. The ones who passed that school went to Little Creek, VA. There they were to be trained in using/repairing a radio under combat conditions. One Navy radio man went ashore with each LST of Marines when they landed on Pacific Islands to retake them from the Japanese. If Earle had passed that class, he might have been at Peleliu, Iwo Jima or Okinawa — on the front lines and under fire.

He and a buddy were delayed from going out to the Pacific by teeth that needed filling (each one had one tooth that needed attention). Then the Navy seemed to forget about them. Both were worried that they would not “see any action.” Both went to Naval headquarters in Oakland and requested immediate assignment. His buddy left before Earle.

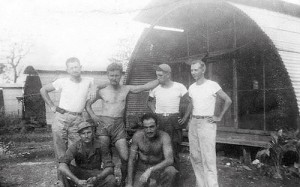

Earle was given sealed orders and told to report for a flight. He never knew where he was going. No one would tell him anything until many hours later he landed in Guam and was told that this was his stop. He spent over a year inside a relatively small base. Every afternoon everyone lined up for his two beers, the highlight of the day. The men assigned to this base became a “ragged bunch.” Discipline was loose. They cut off the sleeves on their t-shirts. They cut their boots into sandals. They swam in a lagoon that was waist deep. He never swam in the open ocean the whole time he was there.

He wrote his mother and a “couple of girls from school.” He rarely received mail. He never wrote Uncle Craig who served as an MP in Manila.

There was no library on base. Bob Hope never came to Guam. One second rate big band showed up one time. That was it. They played cards and talked and swam and worked and drank their two beers.

There was no library on base. Bob Hope never came to Guam. One second rate big band showed up one time. That was it. They played cards and talked and swam and worked and drank their two beers.

1940’s photo of American servicemen on Guam

They went to the movies every night, but the B-29’s taking off for Japan flew at tree-top level right over the Quonset hut where they were being shown. They could not hear the dialogue. He often watched them returning from their missions. He saw a few planes coming back with engines knocked out of commission. He never saw any crash.

He performed several jobs at Guam. For a time he worked twelve on-twelve off shifts. He worked upstairs in a large bunker running errands and typing up logistical reports. He hated that job. It was hot and the work was boring.

He spent most of his time on Guam writing down transmissions of code. Each line had room for ten characters. For example: XCTKO_FAQUP. He did this for each transmission which was then given to a code breaker who translated the message into English. Earle was not a code breaker.

A WW II Naval radio transmitter

The big brass came to Guam after the sinking of the Indianapolis to conduct an investigation. Earle and all the other radio men were asked if they had received any kind of message from the USS Indianapolis around the date that she was sunk by a Japanese torpedo (the Indianapolis carried Little Boy to Tinian). No one had received any messages.

Japanese soldiers would come out of the jungle all the time to surrender. They walked out with their hands raised saying “I surrender. I surrender. No Marines. No Marines.” They were terrified of the Marines. They were put to work breaking up coral or as Earle said, “Making little pieces out of big pieces.”

Earle took a short cut at night through the jungle one time. The path was a mile or so in length. Halfway along the path he heard a rustling in the brush. He remembers saying to himself, “Earle, this was not a good idea.” He never did it again.

At the end of the War, he was the last radioman to leave Guam — last in, last out. He came home in a cargo ship — from Guam to San Francisco. He has not been in contact with any of the men with whom he served on Guam. He does not have a list of their names. He does remember the ‘Chief’, presumably Chief Petty Officer, his immediate superior, fondly. He would like to return to Guam, to see how it has changed, but he knows that that will not happen now.

He was happy to come home.

His neighbor in Merchantville, a high school friend, had been a LT. Commander in the Navy and had brought a hammock home which he slung up between their back yards. Someone in the neighborhood was raising free-range chickens.

One hot summer night his mother suggested he sleep on the hammock. He did so, but said to her the next morning, “I couldn’t sleep. Those f****ing chickens kept me up all night.” Earle said this to me with a smile. His buddies on Guam had talked about using that word one time with their families just to get a jolt out of them. He did not use it again.

Earle and Alma met in the fall of 1946. Earle was 21, newly returned from the War. Alma was 17. He was part of a contingent of 12 to 15 vets who had returned to Merchantville HS in New Jersey to take college entrance courses. Alma had been dating a boy stationed in Korea whose mother was the school nurse. Then Earle showed up.

How it unfolded, in their own words:

Alma: “Magic did not strike. He was a pain in the neck. He was everywhere I was – at my locker, in some of my classes, always looking at me.”

Earle: “I was a pursuer. She was a flee-er. I was a ‘bad boy’.”

He had graduated from high school before being called into the Navy, but he needed a few courses to fulfill requirements for entry to college. Sometimes he left campus at lunch for Camden where he drank a beer and had a sandwich and then returned to afternoon classes. “This did not go over well with the principal.”

Alma: “I was 17 and not ready for a 21 year old guy. He gave me a compact for Christmas and I never used [make-up] powder. He bought a china bird, some .25 cent junk store purchase. I got tired of pushing him away.”

Earle: “I used to wear my cigarettes rolled in my sleeve. I had no money, no clothes. I wore old jeans and sweatshirts. When I got home from the War, I found that my record collection and bicycle were gone. My mother had had to sell them to make ends meet. I belonged to the 52-20 club. Because I was a vet, I received $20 a week for 52 weeks. That $20 kept my head above water.”

Alma: “Senior year was a disturbing year. I thought I would be on my own. Finally I told him that I would not see him until after Valentine’s Day (of 1947). After that, he’d sit in Spanish class and look like the world had killed him off.

I was writing letters to colleges. I had been accepted at Centre College in Kansas, at Trenton State, at the Women’s College of Rutgers, but my parents had also said to me, ‘Why do you want to go to college?’ All the cost would be on me. I was a scared chicken.”

Valentine’s Day passed.

Finally Alma agreed to a date with Earle. On Easter Sunday, April 6, 1947, they drove to Washington D.C. in a borrowed car, an old Chevy with a rumble seat. Earle wore a suit, Alma wore heels. They spent the whole day until early the next morning exploring the city. They visited Mt. Vernon and the White House and very late that night they sat on the steps of the Capitol and watched the city, its lights glittering over a peaceful vista. This date “swung things around,” Alma said.

Finally Alma agreed to a date with Earle. On Easter Sunday, April 6, 1947, they drove to Washington D.C. in a borrowed car, an old Chevy with a rumble seat. Earle wore a suit, Alma wore heels. They spent the whole day until early the next morning exploring the city. They visited Mt. Vernon and the White House and very late that night they sat on the steps of the Capitol and watched the city, its lights glittering over a peaceful vista. This date “swung things around,” Alma said.

A postcard of the Capitol Building, 1948

Earle presented her with a ring on Christmas day. They married on June 18, 1948.

After their marriage ceremony they spent the first week of their honeymoon in Green Lane (Montgomery County) at her parent’s summer home; for good measure they took in a Phillies doubleheader at Shibe Park and saw the Phillies split with either the Pirates or the Cubs.

Then they left for a week in Maine and Earle’s cousin’s cottage facing Capitol Island in Pig Cove on the Southport Peninsula down

Then they left for a week in Maine and Earle’s cousin’s cottage facing Capitol Island in Pig Cove on the Southport Peninsula down east of Wiscasset. Earle told Alma of his boyhood summers spent there. He worked at the Newwagen Inn as a busboy. At 12 or 13 years of age his mother let him row out to Squirrel Island deep in Linekin bay. He never wore a life-jacket. He roamed the woods playing Robin Hood, and and said that “we used to come flying down the hills with our swords.”

east of Wiscasset. Earle told Alma of his boyhood summers spent there. He worked at the Newwagen Inn as a busboy. At 12 or 13 years of age his mother let him row out to Squirrel Island deep in Linekin bay. He never wore a life-jacket. He roamed the woods playing Robin Hood, and and said that “we used to come flying down the hills with our swords.”

Earle in Maine

One day Earle rowed Alma around Capitol Island. She was “amazed at how strong he was, at his big shoulders and arms, and at  how well he rowed.” Earle sat facing her, his back to the bow. Alma said that “time did not matter. We stopped often to get out and walk. At the end of the ride we drifted over water that was so clear we could see the bottom and shells and starfish.”

how well he rowed.” Earle sat facing her, his back to the bow. Alma said that “time did not matter. We stopped often to get out and walk. At the end of the ride we drifted over water that was so clear we could see the bottom and shells and starfish.”

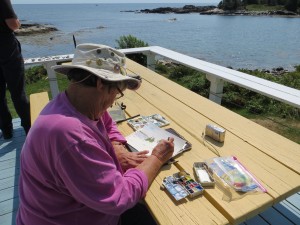

Now, at 87 and 84, Earle and Alma again sat on the deck overlooking islands and the sea, looking at birds and the dogs, happy to have returned to Maine.

Earle and Alma and Patti close to Pig Cove and the route Earle took with the rowboat on his honeymoon.

Earle and Alma and Patti close to Pig Cove and the route Earle took with the rowboat on his honeymoon.