More than twenty years ago we sat across from each other in students’ chairs. She had come directly from work to Parent Conferences, driving through darkness and a storm that rain-lashed the windows of my classroom. Her son was now a junior; I had also taught him in ninth grade. He was a young black man, 17 and a remarkable athlete, very smart, a good writer, handsome, cocky, but with a shy, grand smile that was so purely charming it made teachers smile in return.

More than twenty years ago we sat across from each other in students’ chairs. She had come directly from work to Parent Conferences, driving through darkness and a storm that rain-lashed the windows of my classroom. Her son was now a junior; I had also taught him in ninth grade. He was a young black man, 17 and a remarkable athlete, very smart, a good writer, handsome, cocky, but with a shy, grand smile that was so purely charming it made teachers smile in return.

His mother could be a hard woman, but she had softened with me over the course of almost two years. Tonight she was tired, her body sagging, her eyes watery behind her thick glasses. I do not remember how the subject came up; our conversation had been branching out, flowing back and forth from the personal to the educational. She was worried about her son. She thought he might be growing conceited, too confident, too sure of his place in the world. She was worried that he might let go of a smart-ass remark at the worst time. Somehow she began to tell me about the Instructions, the list of do’s and don’ts that he should observe if stopped by a police officer. I remember most of them: If walking, do not run. Stop. If driving, keep both hands on the wheel. Answer questions with yes sir and no sir. Never raise his voice. Do not argue. Follow the officer’s orders. Keep his voice steady, his face expressionless. Ask for permission to reach into his pocket or into the car’s glove box.

She feared for his life.

I knew about this list. Maybe I had glanced at a story about the Instructions in the Times at some point, but here was a weary mother who had tracked her son all his life, her coat dripping water onto the floor, leaning towards me and looking into my eyes.

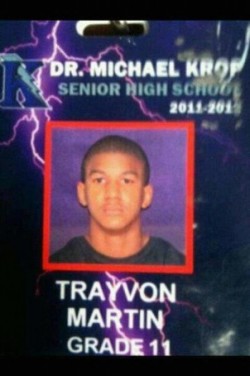

I’ve been thinking about that conversation since Trayvon Martin was shot to death. The acquittal of George Zimmerman in that shooting caused me to go back and try to recapture that moment when she leaned in more closely.

I’ve been thinking about that conversation since Trayvon Martin was shot to death. The acquittal of George Zimmerman in that shooting caused me to go back and try to recapture that moment when she leaned in more closely.

I’ve been trying to see again all the young men I’ve ever taught who smoked some weed and were over-confident about their physical prowess and judgment and how quick many of them were to rise up and assert their masculinity when challenged. I’ve taught many kids like Trayvon Martin. He is real to me — not an icon of any kind, not a cartoonish threat, not an angel.

George Zimmerman left his car to pursue Martin carrying a Kel-Tec PF-9 9mm pistol in a holster under his coat. Would he have left his vehicle if he had not been carrying a pistol? He had seen an intruder. His blood was up. The recorded dialogue with the dispatcher indicated that to be true. Did he feel his moment approaching, a good guy confronting bad guy movie playing out before him?

Trayvon Martin did not run as his girlfriend testified that she told him to do. What was playing out in him? What fears? What perceived insult to his honor as a man? What threat did he see following him in the shadows?

The police never went door to door in his father’s gated community that night* to see if the dead young man lived in any of those homes. His body lay face up on the lawn. The police assumed that he did not belong there. They could not see him.

No one besides Zimmerman knows what happened. He is not talking.

Trayvon Martin is in a grave, his life gone in a brief, cloaked struggle in the rain. Zimmerman said that Martin’s death was “God’s plan.” He would do nothing different.**

Consider this: God’s plan at work in Sanford, Florida, George Zimmerman as His emissary, as His sword.

The President said that if he had a son, he would look like Trayvon. I can cast my memory back to faces in rows and see Trayvon in those faces. They are not symbols. They sit before me, slouched and focused, alert and tired, all of them in some measure impatient to move on, to get on with their lives.

I wish, Mike that there had been more people like you in the juror. Somehow the juror missed so much. Was the lawyer for Trayvon not good enough? Did they miss the obvious facts and go to the spectacular that didn’t mean as much? I don’t understand and I have lost confidence in this process.

Mike, your essay has made me cry, mostly because as a mother to a boy approaching those very precarious teenage years, I am terrified of losing him to drugs, to violence, to stupid decisions. I cannot process Trayvon Martin’s death and George Zimmerman’s acquittal from any other perspective than as a mother to a son, and, again, I am terrified. Thank you for the moving words.

Mike, Great piece. I’m with you 100%.

Thanks for writing, Mr. Wall. It’s a difficult time to process all of these realities, and to know how to respond or how to be a part of the positive change that needs to happen. It’s obvious we can’t continue this way.

Great post, Mike. Your insights and personal perspective are moving.

Spot on, as always, Mr. Wall. Keep writing!