Wednesday, December 16: I heard him before I could see him — the loud voice, vicious in tone — “fuck you, yeah yeah … who the fuck are you lookin’ at, you, fuck you”. I could not find the man. Then, as if the wind had caught them, those walking into and out of the store all turned in one direction. He was sitting in a black sedan parked closest to the entrance, the driver’s window down, his arm gesturing, waving, increasing its wild movements when someone looked at him. Mid-thirties, a hat, a mustache. I thought “gun”. His hand was empty. Inside the store I turned and watched him. He continued for another two or three minutes. He never opened the door. He only cursed and yelled, but I thought gun and tried to think clearly about what to do if he started toward the door, and if he came carrying something in his hand. Instead, the window rolled up, and he pulled away, and thirty seconds later turned into traffic and was gone.

These are days when we have to reckon on the potential for madness in all its forms, its appearance possible even here, a strip mall west of Reading.

In Macbeth, King Duncan, confronted by invasion and rebellion, depends upon his best fighter, Macbeth, to save Scotland. Macbeth wins two battles in one day. Scotland survives. A moment before he appears to receive Duncan’s gratitude for his efforts, Duncan, speaking of a traitor says,”There’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face: he was a gentleman on whom I built an absolute trust.” Macbeth enters, and Duncan welcomes his murderer into his presence.

In Macbeth, King Duncan, confronted by invasion and rebellion, depends upon his best fighter, Macbeth, to save Scotland. Macbeth wins two battles in one day. Scotland survives. A moment before he appears to receive Duncan’s gratitude for his efforts, Duncan, speaking of a traitor says,”There’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face: he was a gentleman on whom I built an absolute trust.” Macbeth enters, and Duncan welcomes his murderer into his presence.

Tens, dozens, hundreds of faces greet your long day. You cannot know their thoughts. You cannot know their “minds’ construction” because those faces might rearrange themselves for any purpose. As can our own. We are built for deception and for keeping secrets, but not well for understanding the treachery of others. Treachery is the shock that always shocks.

We have expectations that we will not be hunted. We have expectations that pity, that most essential human connection, is stronger than murder. We want to keep faith that when we look into another’s eyes we should be able to pick up a clue, a vibe, some trembling sensation in the air, that this man is not right, that he means me harm, that he will set off a primal, evolutionary, animal reaction to threat, some deep appreciation of the monstrous, and that this person I know or stranger I do not is vicious, that he is coming, and he means to do wrong.

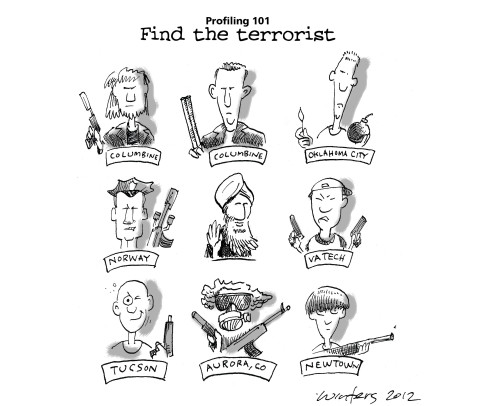

Now we worry that we may have no sense of anyone’s deeper urges or decisions, and that empathy and kindness and welcome purchase nothing, not even a grain of pity, no hesitation at all, and that ideology and a desire for vengeance, disguised by a blank look or a quiet demeanor, are more powerful than fellow feeling. Now we worry about the randomness of these horrors — murder might follow us anywhere — into our workplace or a theater, a church, a clinic, a school, a store. And who might come calling — the deep crazy, the jihadi, the racist, the anti-government goon? White man, brown man, black man? Now we worry that we may have to add women to that list.

Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife Tashfeen Malik walked into the familiar conference room of the Inland Regional Center and began firing AR-15’s from the hip into the bodies and faces of men and women Farook knew well: “Recently, they had thrown a baby shower for him.”* They murdered 14 human beings. They left 21 shattered by wounds. Who murders friends who helped you celebrate the birth of your child? How are we to make sense of this abuse of everything normal and good?

Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife Tashfeen Malik walked into the familiar conference room of the Inland Regional Center and began firing AR-15’s from the hip into the bodies and faces of men and women Farook knew well: “Recently, they had thrown a baby shower for him.”* They murdered 14 human beings. They left 21 shattered by wounds. Who murders friends who helped you celebrate the birth of your child? How are we to make sense of this abuse of everything normal and good?

These are days when we must again consider madness as prompted by ideas — the rational deranged, the reasoning berserk. The twentieth century produced the Nazis and the Communism of Lenin, Stalin, Pol Pot and Mao and this century a monstrous version of Islam as practiced by ISIS, the Taliban, Ansar Blanga** in Bangladesh, Boko Haram in Nigeria.

Primo Levi understood. He both fought the Nazis and survived Auschwitz. He witnessed the poison of ideology in the most personal way possible: “What most clearly stands out … is the experience of violence in service of the absolute—absolute racial purity, for example, or absolute security and freedom, or absolute control over people through force …. For Levi, then, the twentieth century was so violent because societies strove for the absolute and infinite ….”#

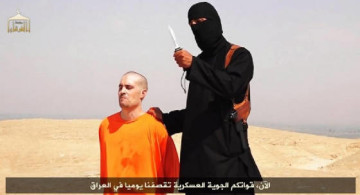

Terrorists in this century are no different. They practice the madness of allegiance without doubt, belief without pause. They choose a clear, immaculate idea over the messy imperfections of each person. For example, ISIS cannot forgive but must treat unbelievers with an impersonal god-like vengeance, a deliberate, practiced indifference to the suffering they inflict, as if their hearts had been removed.

They make the most terrible choice — they will not recognize a common humanity in the vast world of others unlike themselves. They can machine gun children, strap vests on and blow up a market, joyfully ride to their deaths in cars brimful with C-4, behead men on their knees while they play to the camera. They are not insane. They have given up their individuality to a unifying cause, to the perfection of a vision — a world ruled by their people alone, all others to bow before their shining righteousness and truth.

They make the most terrible choice — they will not recognize a common humanity in the vast world of others unlike themselves. They can machine gun children, strap vests on and blow up a market, joyfully ride to their deaths in cars brimful with C-4, behead men on their knees while they play to the camera. They are not insane. They have given up their individuality to a unifying cause, to the perfection of a vision — a world ruled by their people alone, all others to bow before their shining righteousness and truth.

the murder of the journalist James Foley

What are we to do with this fear as we live each day? How are we to combat the possibility of these threats here?

Buy a gun, carry it everywhere we go — to school, the store, the theater, to church? I have thought of this, but even commandos with years of training sometimes shoot the wrong person, the innocent cowering in the corner, the child who suddenly moves. Suppose I am not sure if the one in the beard or the rumpled black jacket is wrong, is doing something suspicious, but I think maybe, maybe. Do I call him out? When do I draw? When do I shoot? Am I to imagine that I would do as well or better than Seals or Marines or SWAT Teams? A late middle-aged man in tri-focals sighting on a swirling glimpse of someone who might be the bad guy and then firing and firing a clip of 17 from a Glock while my hands weave in the air as I duck and cover?

What then? Believe that we can track only the ones who mean us harm, that we can know what lies in their secret hearts, that we possess the clairvoyant power to see the thoughts in their heads, and thus we must build camps here in the US, Pennsylvania Guantanamos, homeland Abu Ghraibs, and shut up those who have done nothing but oh so crafty will, they will do so in time? Or give in to the calls to be afraid that cascaded off the stage at the Republican debate^ as if the candidates were Puritan preachers warning us to look for Muslim devils everywhere, for jihadi witches riding the air and to beware, oh beware.

Fear makes us jittery, irrational, the opposite of calm. It calls forth impulsiveness, hatred, cries for reprisals, the old temptation of an eye for an eye and its twin, a craving to be brutal. Grow fearful enough, and anything is possible — some of us might become the killers we seek to resist and declare all Muslims are the enemy, all brown skinned people, all those we hear speaking a language we cannot understand, anyone in a turban or hijab, any Halal grocery store, any mid-east restaurant, any mosque.

Fear makes us jittery, irrational, the opposite of calm. It calls forth impulsiveness, hatred, cries for reprisals, the old temptation of an eye for an eye and its twin, a craving to be brutal. Grow fearful enough, and anything is possible — some of us might become the killers we seek to resist and declare all Muslims are the enemy, all brown skinned people, all those we hear speaking a language we cannot understand, anyone in a turban or hijab, any Halal grocery store, any mid-east restaurant, any mosque.

And what of those who do not hail from the mid-east and who open fire on the innocent because they are mentally ill, hate women, hate the government, bear a grudge against a boss, a teacher, a classmate, or have been inspired by the venom drifting across the spectrum of American talk shows or web-sites? Their bullets rend the flesh as much as another.

No one person, President, candidate, magician, priest or warrior can keep us safe. Anyone who promises he or she can do so is a fraud. No one possesses certainty on this. However, our lived experience tells us that those we elect should stay cool, examine the problem rationally, seek advice from many, plan a steady, logical course, make prudent policy choices, be flexible, be alert, and take swift action when necessary. Unless you are poor, you are more likely to die in a bed or strapped into your car than by gunfire.

I cannot tell you what I would have done if the man in the car had climbed out and walked toward the store with a gun. I know what I hope I would have done, what I hope I would do. That is all I can say. I do know that we cannot be afraid, that we cannot give killers power over us. Our fear gives them joy. It robs us of peace of mind and threatens our own decency and goodness. This too — we cannot allow politicians to make us into cowards. We are a strong people. We can reckon on our own capacity for courage in all its beautiful forms.

*“Guns And Terror”, The New Yorker, “The Talk Of The Town”. Amy Davidson. December 14, 2015. Page 23.

#“Primo Levi, Mountain Rebel”, The New Republic. Gavin Jacobson. December 15, 2015