In Belfast, Northern Ireland in late December of 1972 as many as eight men shoved their way into the apartment of Jean McConville, a 37-year-old widow and mother who had just stepped out of her bath. They ordered her to dress and come with them. All but two of the men were masked. Jean’s oldest son recognized the unmasked men as neighbors. One man carried a handgun. All 10 of her children were present. Downstairs more masked men waited. Jean was bundled into a van. A man put the muzzle of a gun next to her son’s face and told him to leave.

Two nights before she disappeared, McConville left her apartment to cradle the head of a wounded British soldier and spoke words of comfort to him. The next morning, “they found … graffiti across their door: BRIT LOVER (53).”*

She was abducted the night before her murder, a hood thrown over her head, “taken to a derelict building, … tied to a chair, beaten and interrogated (55).”*

Her body was discovered in 2003. A blue diaper pin she kept clipped to her blouse helped identify her. No one had been prosecuted for her murder.

Using the murder of Jean McConville as the lodestar, Keefe tells the story of The Troubles, the internecine violence and open warfare that has taken the lives of more than 3500 people since 1969. Brokered by the United States, The Troubles ended with The Good Friday Agreement of April 1998.

This book (Say Nothing)* records the aftereffects of this conflict, how the participants, years later, “nursed old grudges and endlessly replayed their worst abominations”, and how “they never stopped devouring themselves (322).”

We learn what happened to Jean McConville. Her name joins her to a face, a family, a history, a life, a legacy. Her name gives her a chance to be remembered outside of the politics that murdered her. Her name gives her a place outside of statistics.

We learn what happened to Jean McConville. Her name joins her to a face, a family, a history, a life, a legacy. Her name gives her a chance to be remembered outside of the politics that murdered her. Her name gives her a place outside of statistics.

In his poem “Six Lectures in Verse”, Czeslaw Milosz writes about “Miss Jadwiga,/ a little hunchback, librarian by profession” who died in the collapse of her apartment building during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Years later, her remains were uncovered: “The little skeleton of Miss Jadwiga, the spot/where her heart was pulsating./This only/ I set against necessity, law, theory.”**

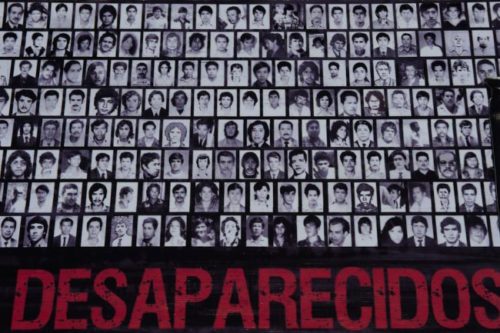

I have been thinking about names recently, about friends, and about the long passed and recently gone from life, and how their obituaries give a precis of their lives. Their names mean they matter. Disappear the name, disappear the person.

I have been thinking about all the names of the Central American children disappeared into the cages and prisons of ICE, of the Uighurs disappeared in Chinese re-education Camps, of the North Korean disappeared, of whole peoples lost to individual memory within the monstrous apparatus of State Oppression.

It makes me double my resolve to see any person before me in as free a way as possible — separate from ideological, ethnic and racial doctrines, free from corporate talk-show opinions, free from cult-worship or approbation. To call them by name. To remember them. To oppose the instruments of erasure and murder employed by all governments to keep their power. “To set against necessity, law, theory” names, faces, histories, the architecture of one life.

*from Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland by Patrick Radden Keefe

**from Selected Poems: 1931-2004