It was there, just that fast, rising up from under the car in front of us, flailing and shredded. For a moment I thought it was something alive before it configured itself into a long, wide piece of tread from a tractor trailer. Hemmed into the middle lane of Interstate 95, rushing along at 65 mph, there was no place to escape.

Its strike came full across the left bumper and it thumped and boomed under us, but the car held steady; nothing immediately blinked yellow on the control panel. I could see nothing from the driver’s seat.

When we were able to stop, the front left bumper had popped and was humped up; an engine pan hung an inch from the road. If it had struck a foot higher, it would have entered the slipstream and cracked the windshield. That shock would have made it harder not to swerve. There were cars all around us. There would have been no margin for error.

Unlike us the seal’s luck had not held it aloof from the force of speed. Wolfie found it rolling in the incoming tide in a foot of water. It bore one mark of a propeller cut. It bore the teeth marks of a shark whose second strike had almost torn it in half. Grievously wounded, it had made it to the inlet for us to find.

Unlike us the seal’s luck had not held it aloof from the force of speed. Wolfie found it rolling in the incoming tide in a foot of water. It bore one mark of a propeller cut. It bore the teeth marks of a shark whose second strike had almost torn it in half. Grievously wounded, it had made it to the inlet for us to find.

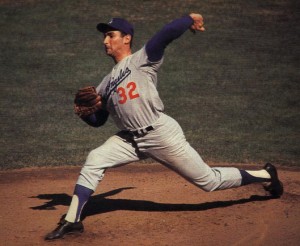

The logic of our experiences always surprises me, as if some unconscious faculty deep within the brain is forever furiously spinning narratives that yearn to be connected. I had been reading Jane Leavy’s book on Sandy Koufax, a remarkable athlete and human being who could throw a baseball at 100 mph, but whose work ethic, devotion to his team and the era’s dim understanding of bio-mechanics led him to regularly throw 300 innings in a season. His speed and his effort brought him traumatic rheumatism. At times “his arm was so swollen that it looked like if you poked it with your finger that the skin would burst (158).”

Leavy tells us that “the efficiency of Koufax’s motion generated greater than usual force. The anatomical advantages inherent in his impossibly long arms and fingers enhanced that efficiency. Maximized efficiency also meant maximized stress. Each pitch was an act of violence. Ironically, by making his body into the perfect catapult, he may have hastened the built-in obsolescence of his elbow (11-12).” His ability to throw strikes at great speed over time wrecked his arm. He knew it was happening. Years after his early retirement at age 30 he said, “I absolutely loved it. How could you do the things I did and not love it (266)?”

To serve that love he endured cortisone shots in the elbow joint. He dosed himself with codeine for pain every night and sometimes during the fifth inning of his games. He took Butazolidin, “an anti- inflammatory prescribed for broken down thoroughbreds so poisonous to living things it was taken off the market in the mid-1970’s (158).” He chose this.

What about that idea of choice governing all the strikes we see carried out around us? Mad Ahab believed in an invisible world replete with malignant agents hovering in the air around us, like seeds carried by wind currents, ones that we might invite in, or ones that might pay a visit, delivering a blow unannounced. Perhaps, instead, the price that we pay for the wrath or the daring of speed is only a function of blind chance, the dice rolling lucky seven or the strikes arriving so fast all that we can do is inhale and wait for the shock and maybe smile while we wait.

Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy by Jane Leavy