I spent my first nine years in rural Pennsylvania in the 1950’s. My earliest outdoor memories are of big apple and apricot trees, hay and corn fields, a narrow lane leading to a stream and woods. Those modest settings were the first landscapes of a myriad number that made nature a haven-life saved next to the one where I work; I was able to lose my self by degrees in both, to be freed in their consolations. Teaching encouraged dramatic, engaged conversations with human beings, individually, in classes and in the voices that rose to me from their essays. It demanded a fully present response, by genetics or good fortune the only kind I could give. Nature’s draw has been more mysterious, its pleasures harder to describe. Now its presence grows stronger, its polymorphic voices more tenacious, the light coming through the big windows of my home a constant reminder that I might be missing something grand out there. How has this come to pass, that an intrinsic part of my happiness has been seized by what lies ‘out there’? Of Nature, Emerson writes, “Let us interrogate the great apparition” so as to see what effects its “floods of life [passing] around and through us must have.”*

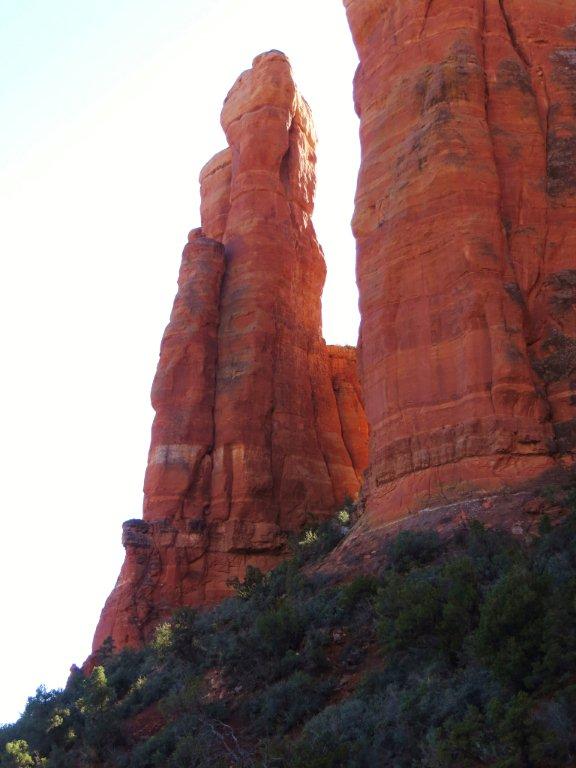

The saddle lay between these two towers.

The saddle lay between these two towers.

That “apparition” arrives in infinite embodiments — one could never come to the end of the list — a single line of wolves in a snow squall moving into a plain, a quintet of crows along a fence rail, a storm-wind bending trees almost double, a dozen radiant-white sycamores in a creek bottom, a grizzly running up a slope and stopping to look back over his shoulder, the first green buds on the trees lighting up gray Paris boulevards in April.

This time, a red tree.

Between two towers of Cathedral Rock lies a narrow saddle maybe 20 feet wide; scrub cactus and sage have anchored themselves in thin soil. Angling out from a cleft below an overhang, a thin tree, about eight feet tall, fed by seepages from above, exposed to direct sunlight for maybe one hour a day. Through a series of random events, its seed blown in or dropped by a bird, it survives. In its brief history I arrive, and when the sun strikes it today, it glows a dusky red and an almost neon yellow. Its presence is transfixing. I must look at it. Doing so causes me to suddenly feel different, but ‘different’ will not do. I am changed, simultaneously calmer and exhilarated. The  alchemy of endorphins activated by the long climb partially explain this elation. Other hikers pass by; a couple sits near us — solitude plays no part in this, but nevertheless an absence of ‘noise’ settles in — I feel zero turbulence, no dissonance inside me at all, only a passage into a euphoric state — Emerson calls this an awareness of the “unity” of the world, that at such moments we have “access to the entire mind of the Creator,”* but sitting here weeks later my skeptical, scientific head rejects this. I do not think I sensed God there. How would I know? That is too reductive, too simple. But that stubborn tree in the rock, in that sudden light, this living thing separate from my bio-chemistry, this surprise, in some way this is a cause of my delight.

alchemy of endorphins activated by the long climb partially explain this elation. Other hikers pass by; a couple sits near us — solitude plays no part in this, but nevertheless an absence of ‘noise’ settles in — I feel zero turbulence, no dissonance inside me at all, only a passage into a euphoric state — Emerson calls this an awareness of the “unity” of the world, that at such moments we have “access to the entire mind of the Creator,”* but sitting here weeks later my skeptical, scientific head rejects this. I do not think I sensed God there. How would I know? That is too reductive, too simple. But that stubborn tree in the rock, in that sudden light, this living thing separate from my bio-chemistry, this surprise, in some way this is a cause of my delight.

My experience of these varied ‘delights’ links me with most other human beings, past and present: “The tradesman, the attorney comes out of the din and craft of the street, and sees the sky and woods, and is a man again. In their eternal calm, he finds himself,”* but Emerson never explained the connection to being and self. How does one become a man again? How does nature provoke him to discover a true self, separate from some less true essence? I recognize Emerson’s references — “sky and woods” do often communicate a “calm.” Something falls away. A tremendous simplicity appears before me (is that the “unity” Emerson senses?), and inside, a motionless space, an equilibrium, a silence where before there had been anxiety. Wendell Berry tries to describe this spellbound state in “The Peace of Wild Things”:

When despair for the world grows in me/and I wake in the night at the least sound/in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,/I go and lie down where the wood drake/rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds./I come into the peace of wild things/who do not tax their lives with forethought/of grief. I come into the presence of still water./And I feel above me the day-blind stars/waiting with their light. For a time/I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Perhaps Berry brings us as close as we can come. I cannot define “the grace of the world,” but I know it when it passes into me. Emerson believed that the “world is emblematic,”* that we make our way towards nature through symbols, through language and images, but a symbolic understanding cannot bridge the gaps between the red tree in one sunlit moment, its strike upon my consciousness, causing it to resound like one long piano chord, and my attempts to communicate it here.

Late Saturday I took the dogs out in the snow. A three-quarters moon cast trees into shadows and made the snow a powder blue. No wind. Very, very cold. Nothing moved but us and when we paused, the world seemed locked into absolute zero. No raptures, no bliss, nothing but a few minutes of silence and the light on the snow. A mystery opens to us at the core of each encounter, and they all add up. Each moment saved couples a little more beauty to a life. That is a sweet and abiding gift.

*from the essay “Nature” By Ralph Waldo Emerson

A note: I have not retouched the photo of the tree. That is it as I saw it and photographed it.

Some of my favorite memories are growing up in rural Myerstown. In the summer, I would get up in the morning, mom would pack me a lunch in a brown paper bag, put water in a glass jar and my friends and I would go “down the lane” on our bikes for the whole day. We would play by and in that stream for hours. Our parents never worried–it was a different time back then, and we would always be back by supper. What a wonderful childhood we have had!!

I was not there. I did not see the tree. but I do believe it is God. Each and every God is personal. As I grow older I respect each and every person’s God. Thanks for sharing!!