I drive this shortcut road 10 or more times a week to the gym and grocery store and whenever I have to cross the Schuylkill River to the north, but it took me too long to pull my car to the side and walk to the marker.

I drive this shortcut road 10 or more times a week to the gym and grocery store and whenever I have to cross the Schuylkill River to the north, but it took me too long to pull my car to the side and walk to the marker.

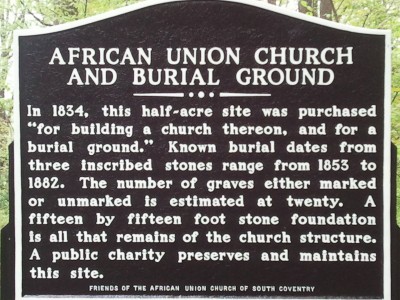

Twenty-six years before the beginning of the Civil War, black men and women, many free of bondage*, built a Church on a rise of what would then have been a lonely fifth of an acre on a dirt road. The African Union Church once rose here. The oldest tree now might be 60 years old. This would have been an open spot then. They would have had a view into the valley of the French Creek and of the succeeding ridge lines fading into the south.

Where did those men and women live? How did they come to this obscure section of Pennsylvania? Some may have walked to this Church from Pottstown. Eight households of free blacks are recorded as residing in the township in 1850.

Where did those men and women live? How did they come to this obscure section of Pennsylvania? Some may have walked to this Church from Pottstown. Eight households of free blacks are recorded as residing in the township in 1850.

According to the 1850 census, the men made their living as laborers. Where did they work? I know that some were employed by the Potts family at their Forge three miles from here, to the southwest and one valley over. I have been told that others may be buried under a big oak on the private land of that enormous estate.

What did they talk about?

What stories did they tell?

Three grave stones remain. One has been eroded almost into blankness, but in 1944 someone transcribed the engravings of all three, and that is how we know that Susan Williams, wife of Richard and daughter of George and Eliza Chester, died in April of 1853. She was only 40 year old.

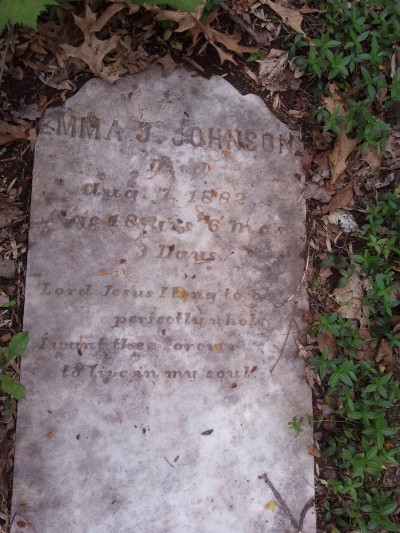

One made of white marble lies flat on the ground. Emma Johnson is buried here. She died on August 7, 1882, a young woman of 18 years, 6 months and 3 days, as if whoever chose these words believed her life, every moment of it, was beloved, and therefore to be counted to the day. Her inscription reads: “Lord Jesus I long to be/perfectly whole/ I want thee forever/to live in my soul.”

One made of white marble lies flat on the ground. Emma Johnson is buried here. She died on August 7, 1882, a young woman of 18 years, 6 months and 3 days, as if whoever chose these words believed her life, every moment of it, was beloved, and therefore to be counted to the day. Her inscription reads: “Lord Jesus I long to be/perfectly whole/ I want thee forever/to live in my soul.”

The second stone has been broken, its fracture line cutting off the first name. “[John] Thomas” is buried here, born in 1802, gone on October 1, 1874: His inscription: “Therefore be ye also ready/for such an hour as ye [think]/ [not] the Son of Man [cometh].”

Emma Johnson and John Thomas almost certainly would have known each other; they attended the same church. Perhaps he once held her in his arms when she was an infant. They would have looked out upon the same green landscape, dotted everywhere with farms. Some of the iron forges were still operating — the hills would have been bare, their trees taken for fuel.

A rough stone wall seems to delineate the back line of the property. A square foundation hole of an obscure purpose “is all that remains of the church structure.” Standing here, I feel a certain reverence, the kind one adopts in any place where the dead have been laid to rest, and so I am quiet in my movements and often still. A few cars pass by. I can turn and see homes all around me. A cardinal’s song cuts sharply through the woods. Then quiet returns.

I wonder if their descendants, if any, live nearby. I wonder if they had a bell that was rung to call to worship. Two more churches as old as this one lie within a mile. It would have been pleasant to listen to those bells roll out their chimes on early summer mornings. On clear days, with a breeze from the northwest, their conjoined voices raised in hymns would have been audible, each to the other.

*Please look at the timelines offered on the FAUSC site. Someone has done marvelous research.