I wonder about the mysteries of ruined men*, especially the contrast with those who have found ways to call a truce with their heartaches and ordeals.

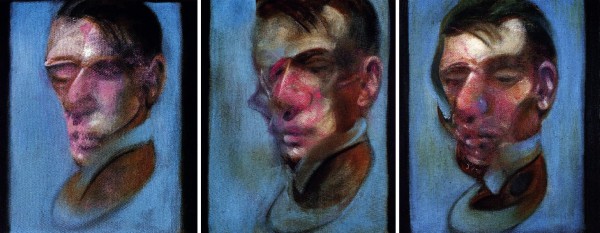

Self-Portrait by Francis Bacon

I have seen men who look haunted, whose eyes gaze at me and yet do not engage, who seem unnerved and twitchy. Fathers at school conferences who I knew had come to the end of something – a job, a marriage; whose grief went so deep that their disappointing children annihilated them when my sentences reported on their normal disorders and confusions. Men of a certain age who seem unmoored, as if their usefulness had run out. They watch so much television that living people seem too much trouble; they take too much effort, unlike the comforting ones on the screen who entertain without asking for anything in return.

I have seen men who look haunted, whose eyes gaze at me and yet do not engage, who seem unnerved and twitchy. Fathers at school conferences who I knew had come to the end of something – a job, a marriage; whose grief went so deep that their disappointing children annihilated them when my sentences reported on their normal disorders and confusions. Men of a certain age who seem unmoored, as if their usefulness had run out. They watch so much television that living people seem too much trouble; they take too much effort, unlike the comforting ones on the screen who entertain without asking for anything in return.

There are others whose expressions can be equally ghastly though their grim looks take many forms. We have all seen someone well-off, whose money concerns have evaporated, looking as bleak as a Dickens’ orphan.

I used to believe that character was fate, as Heraclitus charged; that we created our lives based on our choices and those choices were corkscrewed inextricably into our characters. They rose from our natures like water vapor off a lake. The lucky were the good. The ruined had simply obeyed the destiny implicit in their sorry selves.

Now, I think I was wrong.

What the Greeks believed was the handiwork of the invisible Gods, we know as circumstance, chance encounters with bad luck, genetic leanings, or simply opening the most profoundly wrong door at the worst possible moment.

Think of those who have been so struck … or better, just look at one’s own history – financial traumas, difficulties with a child, the strains that arise in sustaining a marriage, the potential calamities in the temptation of booze or weed or worse, the slow motion breakdown of the body, bad teeth, lost hair, lost dreams, and perhaps, most terribly, the malignant monthly worry about having enough money to keep a family in food, clothing and in a home, an anxiety that will often metastasize into other arenas of one’s life until each waking second is filled with unease.

The longer we are lucky enough to go on, the more this question becomes inappropriate: What happened to them, the ruined ones?

Instead, these are the right questions: What happens to us? How are we to respond? We are all in the process of becoming rubble.

The men I admire all had and have a sense of propulsion. They move forward, but never in straight lines. Those puffed up martinets always seem the most intolerant and narrow minded, as if they are certain that their successes have endowed them with a ruthless wisdom, but one that feels as impersonal as ice.

No, the men I admire have stumbled forward, twisting and lurching. They leave a track as random as someone trying to find shelter from a storm; this way and that, over that hill and then a doubling back to this protected hollow.

These men have found ways to accommodate themselves to agony. They do not give in to it so much as find a space for it and then trap it there for as long as they are able. They carry their scar tissue without granting it the right to define their story. The cancers they have survived, both physically real and metaphorical, have given them a persistent sympathy for others who have also suffered all manner of tempest and wreckage.

Maybe tenacity, that terrier’s extension of courage, is the indispensable virtue, the one that shakes us so that we take the next step instead of falling into a sedentary despair?

Maybe insouciance is the solution. Do we not universally like the man who can throw off the wounds inflicted by the world and laugh?

Maybe finding ways to be of use, to make a new ambition of each morning, maybe that is engine that keeps us moving?

Years ago I watched Dick Cavett interview Marlon Brando; Brando was a tough man with whom to talk, but later at dinner, away from cameras, he relaxed and became genial. At one point Brando said that he envied Cavett. Cavett was surprised. He asked why? “Because you act as if nothing is chasing you,” Brando said.

If true, Cavett was fortunate. I do not know one person my age who is not being pursued. Maybe everything comes down to whether we turn on our pursuer and say, “Yes mother******, what do you want?”

And then, take our chances.

*I have not written about women in this Post because, first, I believe there are profound differences in how men and women respond to life’s hardships, and second, I do not think I know enough to write about them yet.