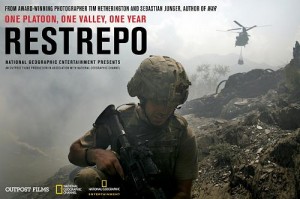

In late November of 2007 I was looking forward to time off for Thanksgiving and to a big family dinner. I did not have to worry about my car being blown off its wheels as I traveled back and forth from school. I did not have to examine every person on the road for some hint of trouble — a cell phone taken out as I drove past, or a blank stare, utterly inscrutable, on the face of all the men in the cars next to me at the light. I did not have to carry 60 pounds of combat gear on my body when I walked quickly up the steps to the main door of the high school. I did not have to wear a sixth sense for danger like a second skin. I did not have to carry the memory of friends’ sudden, impossible deaths. A few men and women on the other side of the world, in Iraq and Afghanistan, did have to be alert to all of those possibilities, and specifically, so did the men of Battle Company of the 503rd Infantry Regiment and the subjects of Sebastion Junger and Tim Heatherington’s documentary Restrepo, named after one of the Company members killed in action. They held an isolated outpost deep in eastern Afghanistan. They pushed out in patrols into dangerous country.

In late November of 2007 I was looking forward to time off for Thanksgiving and to a big family dinner. I did not have to worry about my car being blown off its wheels as I traveled back and forth from school. I did not have to examine every person on the road for some hint of trouble — a cell phone taken out as I drove past, or a blank stare, utterly inscrutable, on the face of all the men in the cars next to me at the light. I did not have to carry 60 pounds of combat gear on my body when I walked quickly up the steps to the main door of the high school. I did not have to wear a sixth sense for danger like a second skin. I did not have to carry the memory of friends’ sudden, impossible deaths. A few men and women on the other side of the world, in Iraq and Afghanistan, did have to be alert to all of those possibilities, and specifically, so did the men of Battle Company of the 503rd Infantry Regiment and the subjects of Sebastion Junger and Tim Heatherington’s documentary Restrepo, named after one of the Company members killed in action. They held an isolated outpost deep in eastern Afghanistan. They pushed out in patrols into dangerous country.

The movie shows these patrols, their dealings with local villagers, their playfulness together, their camaraderie, their grief and devastation, their firefights. Separated by language and culture from the country in which they are fighting, they live as perpetual strangers in a chaotic environment where they can never be sure what is real. They must deal with an ongoing disorientation, and they do so by turning inward to their mates.

Close up head-shot interviews are interspersed throughout the movie. These are after-action interviews. The men have had time to reflect upon their deployment. None of them any longer seem like boys. All of them carry a burden of seriousness in their expressions that is at odds with their youth. You can see the older men behind the unlined faces. Maybe that is the point. Men and women like them, like some of the kids I taught, gave some part of their youth to us. Whatever their motivations for entering the Corp or the Army — a desire to break up a boring life, an authentic belief in duty, a curiosity to see how they measure up — they stepped forward and ended up in Khan Nesin or Fallajuh or Marjah or some hole in a valley that never received a western name.

Actions create moral standards. Their sacrifices and those of their families may be the only safe area left in the blood feud between Republicans and Democrats. Both sides honor vets. Both sides believe in offering them thanks. I think most Americans would be joyous if President Obama and Governor Romney called a press conference tomorrow and offered those vets and their families as the essence of a new American ethic, one based on sacrifice and the good of the whole, one based on what we owe rather than what we can claim, one that rejects both greed and entitlement.

Ten minutes after finishing the movie, I walked down an empty lane at dusk. The road behind me was a blank. A dense, scrubby wooded tree line stretched out on my left for 200 yards. Even, thick rows of shiny green corn stalks, corkscrewing in the heat, most as high as my waist, lay at my right hand. I tried to read this terrain as if my life depended upon my skill. Fifty men intent on killing me could have been watching me, and I would not have known. I can imagine this — the feeling of bone deep fear settled inside a strongbox created by training — but that is a metaphor. I can imagine a metaphor, but I cannot touch any part of the breathing, hurrying, focused momentum of a man or woman trying to do a job while expecting to be fired upon. I cannot. Nor can anyone else who was not with them or who did not share a similar experience.

I saw a few crows hurrying to roost. Some small animal moved in the brush. That’s all. I walked home to air conditioning and to a bed and to a safe place.