When power is at stake, purity and fear are natural allies. Bear with me please in my recitation of quotations. I want to build a case.

Anne Applebaum’s history of the Soviet Union’s prison system, Gulag, contains a chapter on “the years 1937 and 1938 – remembered as the years of the Great Terror (92)” … when “the Revolution devoured its children… (96).”

“The lowest numbers [of those who were murdered] credit Stalin with killing 20 million during the Great Terror alone.”*

These are numbers from one murder order dated July 30, 1937:

From Azerbaijan, 1,500 to be shot; from Armenia, 500; from Belorussia, 2000; from Georgia, 2000 (95). The list progresses in alphabetic order; all the numbers have been rounded to end in zero — many more such orders were processed during the Terror.

Think about those rounded numbers, about their organizational aspirations. These are quotas, not a list of actual targets by name. Shoot x amount of ‘enemies’ these lists decree. So what would have happened if an administrator had only shot 1422 or 301 or 1677 instead? Or if he had replied, “This is madness!”

The rounded numbers had to be met. ‘Enemies’ had to be discovered to fulfill the quota. The purity of the number demanded a purity of response. The chief administrators in each district of the USSR knew that their compatriots were being tortured and shot in the cellars of the Lubyanka. No one objected. This is what happened instead: “The NKVD administration in Moscow expected their provincial subordinates to show enthusiasm, and they eagerly complied.’ We ask permission to shoot an additional 700 people from Dashnak bands, and other anti-Soviet elements,’ the Armenian NKVD petitioned Moscow in September 1937 (95).”

“In Solovetsky, the selection of prisoners for murder appears to have been random (107).”

“Some scholars speculate that the NKVD assigned quotas to different parts of the country according to its perception of which regions had the greatest number of ‘enemies.’ On the other hand, there may have been no correlation at all (94).”

In describing the purge of the Gulag’s camp commanders and top administrators: “The records of their cases have a surreal quality … as if … frustrations had come to some kind of insane climax… (97).”

Again, describing the executions of some of the top administrators: “It was as if the system needed an explanation for why it worked so badly – as if it needed people to blame. Or perhaps ‘the system’ is a misleading expression: Perhaps it was Stalin himself who needed to explain … (97).”

In describing the end of the Terror in November of 1938: “Perhaps the purge had gone too far, even for Stalin’s taste. Perhaps it had simply achieved what it meant to achieve. Or perhaps it was causing too much damage to the still-fragile economy. Whatever the reason … (107).”

Anne Applebaum is a superb historian. She probably understands more about how the USSR operated in its prison camps and in its oppression of vassal states than any other American scholar. She had access to Soviet archives. She lives in Poland and thus dwells within the USSR’s old killing grounds.

And yet, even she cannot definitively account for the motivation behind the mass murders. Count the qualifiers she uses; I have highlighted them in red.

I know no better.

Perhaps we are so often creatures fortified by fear that we make ourselves long to be obedient. Combine that with a desire for protection, and we will agree with most ideas that come from an authority. Or perhaps I obey if I know that the percentage probability of my being arrested, tortured and shot becomes a very high number should I say ‘No’ to that authority. Or it may be that I am an honest believer, and that the pursuit of ideological, religious, or economic purity should be conducted without regard for the law or ambiguity or free expression.

Purity thus becomes a theological notion, a pursuit of an explanation — how does god relate to the world of men and women? By decree, which the faithful are to follow. By an exercise of will which is not to be opposed. Questions create doubt, and doubt breeds resistance — therefore, among fanatics, theology is the sworn enemy of doubt and forbearance.

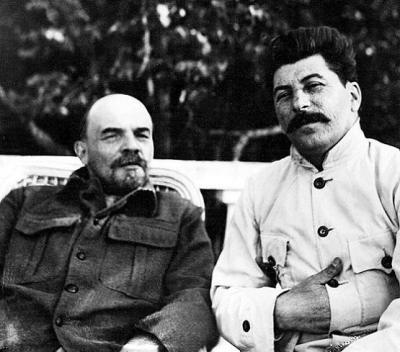

Whatever his form, in this case Stalin in the USSR from 1926 to 1953, god and his iron dogmas always retain precedence over the imperfect strivings of ordinary people for space to think their own thoughts and raise their children to be hopeful.

Tyrants may grant life and take it away. These secular gods demand purity and fear both. They must inspire belief and terror.

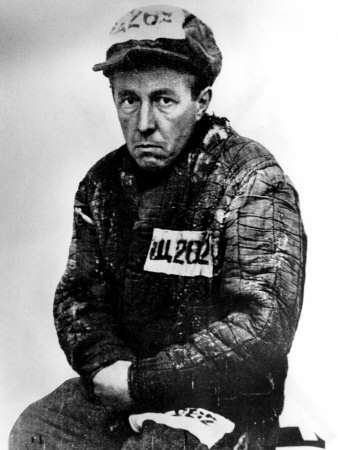

Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag photo

Very few oppose this overwhelming force, but those who have done so deserve to be remembered for their incomprehensible courage — Anna Akhmatova, Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Osip Mandelstam, Vladimir Bukovsky, Garry Kasparov, the collective Pussy Riot, Anna Politkovskaya and the 200 or more journalists murdered since 1989.

I am always surprised by how long this list could be. If I spent the time to do so, I could add tens of thousands of names. Perhaps such courage is the real mystery of evil — how inevitably, it calls forth its opposite.

*About.com: 20th Century History

Anna Politkovskaya, journalist, murdered on October 7, 2006, Putin’s 54th birthday

Anna Politkovskaya, journalist, murdered on October 7, 2006, Putin’s 54th birthday