I know a path covered by low trees. Dunes rise up on either side. Birds call and loop from thicket to thicket. The susurrus of the ocean. The trees thinning. Light. More light. The path is lower than the sea, and then it rises, and in winter suddenly, in one long sighing vision, the bluest water appears, the white empty beach, the cry of gulls, the bluest sky, the surf washing everything clean.

All that lies far away from me. Darkness covers my house. Trucks chuff past the windows. But when I put words to the memory, it comes back.

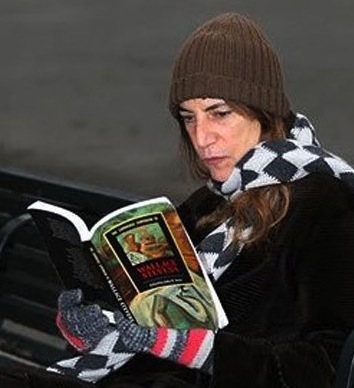

Stevens* tells us that “the poem refreshes life so that we share,/ For a moment, the first idea….” The first idea is always primal, the shock of first sight, the shock of the view that turns the mind around.

Our love of beauty is as primal as our capacity for carnage and much more a kin to our essential natures. We look, light strikes the eye, the brain pan constructs the image, we measure, we feel, and then if the image, the experience, the rush of this moment in life is vivid, we take what has been outside of us and convert it into words, and when we tell the story, the words expand into sentences. Poets shape the sentences into rhythms and beats and make beautiful things that stick in the memory and give the beauty of that blazing time a chance to go forward in time, to last, to be taken in by others and tied to their lives. Poetry expands the way a galaxy expands, star by system by star cluster by light year. We carry the exaltation of which poetry is capable within us because it also lies scattered in the world, awaiting us. Real or only dreamlike, the world may resolve itself in poetry.

Our love of beauty is as primal as our capacity for carnage and much more a kin to our essential natures. We look, light strikes the eye, the brain pan constructs the image, we measure, we feel, and then if the image, the experience, the rush of this moment in life is vivid, we take what has been outside of us and convert it into words, and when we tell the story, the words expand into sentences. Poets shape the sentences into rhythms and beats and make beautiful things that stick in the memory and give the beauty of that blazing time a chance to go forward in time, to last, to be taken in by others and tied to their lives. Poetry expands the way a galaxy expands, star by system by star cluster by light year. We carry the exaltation of which poetry is capable within us because it also lies scattered in the world, awaiting us. Real or only dreamlike, the world may resolve itself in poetry.

Patti Smith reading Wallace Stevens

In 1923 an ocean liner carrying Stevens and his wife passed the Yucatan. It never docked. Stevens tells us that poetry “made him see how much/of what he saw he never saw at all.”** The passage alone, and his imagined forest visions gave him this:

“In Yucatan, the Maya sonneteers

Of the Caribbean amphitheatre,

In spite of hawk and falcon, green toucan

And jay, still to the night-bird made their plea,

As if raspberry tanagers in palms,

High up in orange air, were barbarous.”***

The pleasure of the stanza lies in its colors and melody. It summons an ideal of beauty romantically conceived out of the sea air and the sounds of tropical birds — Stevens knew both of those by experience, but nothing of Mayan sonneteers and their choices of inspiration. His revelations clear away territory for beauty and for its connections too numerous to track. He knew how to make beautiful places using the alchemy of his poems.

Yet another vision in “Sunday Morning”:

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

Such beauty argues against nihilism. It lifts a day out of the routine expenditure of time. Beauty gives us reason to believe in the fundamental goodness of life. In its manifestations we find faith in something greater than ourselves — in a friend, a river, paintings, work, a dog, birds, books, a meal, one mountain, a child, children, songs, a symphony, poems.

A poem is not the thing itself, the experience we can touch, the vista, the face, the breeze on the skin. It is the repository that preserves those memories, and in preservation of that which is transitory, it achieves a limitless grace: Donald Hall, from “Names of Horses”:

“For a hundred and fifty years, in the Pasture of dead horses,

roots of pine trees pushed through the pale curves of your ribs,

yellow blossoms flourished above you in autumn, and in winter

frost heaved your bones in the ground – old toilers, soil makers:

O Roger, Mackerel, Riley, Ned, Nellie, Chester, Lady Ghost.”

Poetry will not save the world, but it will keep that which is best close to us. It quickens our appreciations, it can repair a bad hour, it consoles and it recovers, that more than anything, it recovers that which has been missed or strayed or even lost. Even home. Even love:

Dusk In My Backyard

The long black night

moves over my walls:

inside a candle is lighted

by one of my daughters.

Even from here I can see

the illuminated eyes, bright

face of the child before the flame.

It’s nearly time to go in.

The wind is cooler now,

pecans drop, rattle down-

the tin roof of our house

rivers to platinum in the early moon.

Dogs bark & in the house, wine, laughter. by Keith Wilson

*Wallace Stevens **from “Sunday Morning” ***from “The Comedian as the Letter C”

*Wallace Stevens **from “Sunday Morning” ***from “The Comedian as the Letter C”

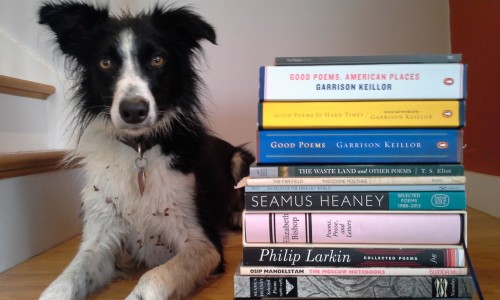

A personal note: I am reading more poetry now than ever before. I wish I had done so while I was teaching. It would have changed everything about how I approached it with kids. I can recommend some books, a short list, incomplete, but maybe one of them will be the book for you:

Elizabeth Bishop, Library of America edition.

Crow by Ted Hughes

All three anthologies by Garrison Keillor: Good Poems; Good Poems for Hard Times; Good Poems, American Places

The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen

Selected Poems of Anna Akhmatova, W. H. Auden, Seamus Heaney, Philip Larkin, Rilke, Wallace Stevens

Citizen by Claudia Rankine

Diving into the Wreck by Adrienne Rich

Here, Bullet by Brian Turner