When I hit him, I felt nothing at first except the shock to my arm and chest. He went down as if he had fallen into another dimension, not the one we had been inhabiting seconds before. I was standing at a great height above him. The others were gathered in a semi-circle on the edges of something far away. I was roaring words; I don’t know what. I sensed a furnace heat inside me, and that it was pouring out of my eyes and mouth; it was in my roaring voice. In my adrenaline powered delusion, I would have fought anyone, all comers, and won. My God, it felt good. And then, that quick, came the remorse and fear (Thank God), and a friend my age came into focus, moaning and holding his hands over his face, blood on his hands and on the ground.

When I hit him, I felt nothing at first except the shock to my arm and chest. He went down as if he had fallen into another dimension, not the one we had been inhabiting seconds before. I was standing at a great height above him. The others were gathered in a semi-circle on the edges of something far away. I was roaring words; I don’t know what. I sensed a furnace heat inside me, and that it was pouring out of my eyes and mouth; it was in my roaring voice. In my adrenaline powered delusion, I would have fought anyone, all comers, and won. My God, it felt good. And then, that quick, came the remorse and fear (Thank God), and a friend my age came into focus, moaning and holding his hands over his face, blood on his hands and on the ground.

I was 16 when this happened, my last aggressively violent moment, a callow boy caught up in a flaring of tempers, and even though I broke up dozens of fights as a HS teacher, and skirted the spiky edges of more serious violence as a younger man, I have not struck another with such force since this fight, but I remember this moment in as clear a set of images as I do the faces of the people I have loved. I don’t know what that means.

I was 16 when this happened, my last aggressively violent moment, a callow boy caught up in a flaring of tempers, and even though I broke up dozens of fights as a HS teacher, and skirted the spiky edges of more serious violence as a younger man, I have not struck another with such force since this fight, but I remember this moment in as clear a set of images as I do the faces of the people I have loved. I don’t know what that means.

Fistfight from a Russian woodcut

Two provocations drove this memory’s return — the apprehensive wait to see what more happens in Syria, the most recent crucible of agony and horror in the Arab lands, and in one of those flash effects that obey a certain moment of incitement, a voice telling me a story.

I was listening to Will Patton’s narration of Creole Bell, a Louisiana thriller about a Homicide officer and his good friend, a massive brawler who in the sequence that had set off the memory had just wrecked a sadist in hand to hand combat. I could feel the pulse in my hands and fingers rising against the hard surface of the steering wheel. I was rooting for the brawler to hammer him; vicariously, I wanted justice extracted through blood. In my real world, traveling in a car at 45 mph, my body was invested in this fictional moment of vengeance for terrible wrongs done to the weak and undeserving.

I could never have kept count of the number of revenge movies and TV shows I’ve seen and score-settling sequences in novels I’ve read, but they all tap into something atavistic in me, in most males too I suspect. Violence is a primal response.

I could never have kept count of the number of revenge movies and TV shows I’ve seen and score-settling sequences in novels I’ve read, but they all tap into something atavistic in me, in most males too I suspect. Violence is a primal response.

Photo by Arthur (Weegee) Fellig. Man shining light on body of Carlo Tresca, New York.1943. Museum of the City of New York

In my fortunate experience, it has been muted. Good parents, peaceful communities, good schools and luck have held it away from me and most people I know, but I have taught students who later murdered. A neighbor I had often spoken with murdered his wife and killed himself. On a personal level, it has leaned against my door.

On a personal level, where individuals kill individuals, cities and whole regions can crackle with violence as if geography were to blame. Central America seems aflame with murder with desperate Guatamala and El Salvador, ruined by oppression and civil war, staggering through blood, and Caracas in Venezuela looking like the opening location of our species’ collective nightmare.

The tribal inventory of violence is older than recorded history; this is its litany — my blood and my people, our freedom, our land, my power, my vengeance. Then nation states took up the same litany, and without respite, the new millennium has seen a continuation of massive violence by and within those states: in Afghanistan, Iraq, Darfur, the Congo where as many as four million may have died, Chechnya, and in the Mexican Drug Wars; in Syria over 100,000 have been killed. Violence begets violence and gives birth to cycles of hatred and ruin. Auden understood. In September 1, 1939 he wrote, “I and the public know/What all schoolchildren learn,/Those to whom evil is done/Do evil in return.”

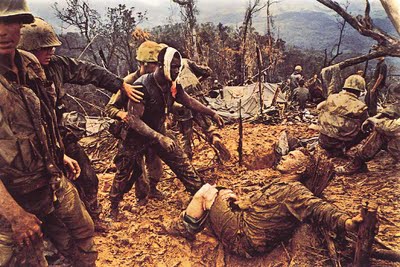

A Harry Burrows photo, Vietnam, 1966

And yet violence is also sometimes obligatory. Power mad men wield violence to gather more power. They will not listen to reason. They roll over pacifists with tanks. Sometimes they must be opposed with violence because no other option is possible except death or enslavement. How else to deal with men like this:

“If your kids are disloyal to Bashar, the Army will f… your women, and we will raise children who are loyal to him.”*

For him, and men of his ilk, the screaming of victims is a momentary inconvenience, nothing more.

And yet violence is also always barbarous and creates victims and fiends. It brutalizes all who come near its compelling, charismatic flame. It can break apart those who wield it:

“What …is going on in my mind? Last night I was sitting in bed and looked across the room to a chair … and there was a young girl covered in blood. What happened after that… a full scale panic attack. This is not the first time I have seen dead bodies. For a while I used to find dead Iraqis floating in my bathtub? Why they were in the bathtub I will never know. I FEEL SO F’ING VIOLENT RIGHT NOW.”**

Iraq

Violence might leave an unreal impression that shows itself in detachment. Once a former student who had become a Marine, returned from Fallujah with his computer filled with photos of bodies, whole and dismembered, burned, smashed, shot, blown up, thrown down by roads, on roofs, lying in sewage, in bare rooms, on barren ground. I asked why he had taken those shots and why he kept them now. He told me that he had trouble believing what he had seen. The images in his head began to seem merely like a movie. These reminded him that he had been in the middle of it.

He had been inside History at its most violent. All of us are enmeshed in History, but he had seen those who were hooked inside its more merciless and savage mechanisms every_day; their questions and subsequent decisions so extreme as to be unimaginable to those of us who live in relative peace and under the rule of law – where do I next eat? how will I survive this night? who must I bribe to stay in the shadows? do I kill or do I run? how do I protect my family from daily threats? and his own questions — is that flapping piece of garbage just garbage or an IED? are my friends safe? should I cross the street here or there? where are their snipers? who is enemy, who friend? and therefore, who do I shoot, who do I spare?

Two ‘devils’ — Himmler and Heydrich

We alternate between taking on the form of a creature beyond the animal, the word devil still best describes it, who can perform appalling deeds while the eyes remain calm and calculating — then we can reverse course and show ourselves as animals with souls who use violence altruistically to stop harm being done to others, especially children and the defenseless. I have weapons in my home, and I know in my marrow that I would use them to defend my family, friends, children. I also know that I must never become careless and casually mock-heroic about such statements. If I pick up a gun and point it at another, everything changes. With a few ounces of pressure, I can destroy whole worlds. Rage and fear can add those few ounces. I am no angel. History tells us that none of us are.

On a summer day when I was 12 or 13, I was chasing a boy behind the neighborhood school. Faster than me, he juked in and out of the swing sets, mocking me, shouting ugly things I no longer remember. On the run I reached down and picked up a cast iron drain lid from the gravel. One side of it was broken and very sharp and jagged.

I threw it as some movie-warrior might spin out a throwing star. My reaction was instantaneous: I thought it was going to rip his head apart. It skimmed past his left ear by a few inches. I stopped. I could not catch my breath. All my fury drained out. I was sick with fear and relief. What had I almost done?

The two stories I tell of my own experience here contain shocks of recognition – of the capacity of an ordinary person to commit violence out of rage, and in one of them, an object lesson in violence exercised, as I thought of it at the time, as a right, as a righteous response. The urge to violence arose in me like a fever that had been lying dormant all along, just under the skin, ready to break through. In both instances an abrupt awakening of conscience followed. The importance of conscience is a good place to end.

After the Occupation of France and the full disclosure of the War’s horrors, Camus also pondered how decent human beings should act in moral landscapes made desolate by depravity. He said that we can be neither victims nor executioners. No pacifist, he fought against the Nazis, but found what might be the only middle way through the complexities that violence creates.

One of the 5 of 6 novels or plays that have most profoundly shaped me is For Whom the Bell Tolls by Hemingway. At the end, the hero, Robert Jordan, an American fighting against Franco, his leg smashed, waits in ambush for the Fascist cavalry. He will give up his life to protect the retreat of his friends and his lover. Lying prone behind a Lewis gun, he thinks about what he is doing: “Each one does what he can. You can do nothing for yourself but perhaps you can do something for another (466).” Later, when he is desperate to keep from passing out: “And if you wait and hold them up even a little while or just get the officer that may make all the difference. One thing well done can make-–(470).”^ Jordan will kill as many of the enemy as he can before he dies. Others who are also set against fascism will live because of his sacrifice. He employs violence against a great evil, and arguably, kills and dies while affirming the value of life.

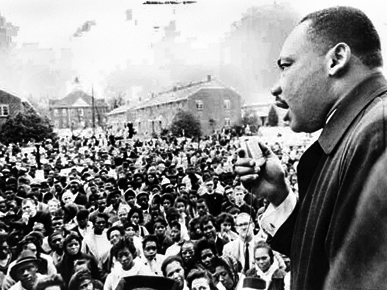

We do have examples where “the better angels of our nature“^^ found tactics whereby racist violence was turned back on itself, and by a kind of exemplary judo awakened a collective American conscience that repudiated this kind of brutality. The bodies of marchers were offered up to the violence of the State.

Martin Luther King, speaking after the First March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama (the first ended in police mayhem, bloodshed, cracked skulls): “We must let  them know that if they beat one Negro they are going to have to beat a hundred, and if they beat a hundred, then they are going to have to beat a thousand (64).”^* Even more explicitly, Ralph Abernathy offered this prayer while preparing for the Second March: “We come to present our bodies as a living sacrifice…. (76).”^^* My experience has shown me that sacrificial love as illustrated by Hemingway and exercised by Abernathy and King is every bit a part of our natures as is our potential for violence.

them know that if they beat one Negro they are going to have to beat a hundred, and if they beat a hundred, then they are going to have to beat a thousand (64).”^* Even more explicitly, Ralph Abernathy offered this prayer while preparing for the Second March: “We come to present our bodies as a living sacrifice…. (76).”^^* My experience has shown me that sacrificial love as illustrated by Hemingway and exercised by Abernathy and King is every bit a part of our natures as is our potential for violence.

MLK in Selma

I wish I could argue that we are more peaceable than bellicose, but that would be a wish and not the truth. It is as if the blood that keeps us alive is a brew of hormones and chemicals that are both demonic and saintly, cruel and benevolent, capable of fueling enduring love and enduring hatreds, toxins and cures. Our hearts serve as weapons and as catalysts for peace. Around and around and around we go. Once more Auden got it right when he wrote that “The desires of our hearts are as crooked as corkscrews.”^^**

*attritubed to Atef Najib, Security Services Director in Dara Province, Syria (a cousin of Bashar al Assad); from “City of the Lost” by David Remnick: The New Yorker, August 26, 2013

**from “The Return” by David Finkel: The New Yorker, September 9, 2013

^Hemingway gets the terrifying moral complexity of the scene exactly right. The man Jordan will almost certainly kill is Lt. Berrendo, a good man caught, like Jordan, in circumstances that he would not have chosen.

^^from Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address

^* and^^*from At Canaan’s Edge by Taylor Branch

^^** from Death’s Echo by W. H. Auden

Cover Painting: That 2000 Yard Stare by Tom Lea

Excellent, Mike.

My thoughts turned to Thomas Hardy’s poem

The Man He Killed. He speaks about war and our

individual love for man.