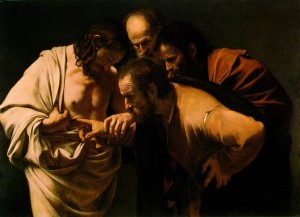

Thomas will not believe. He wants to place his hands inside the wounds. He wants the body, revivified, identified by wounds he presumably saw inflicted, to appear before him: “Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I will never believe (John: 20:25).”He wants Christ to come back to him. He obeys his own sense of what is possible. He believes in evidence.

Thomas will not believe. He wants to place his hands inside the wounds. He wants the body, revivified, identified by wounds he presumably saw inflicted, to appear before him: “Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I will never believe (John: 20:25).”He wants Christ to come back to him. He obeys his own sense of what is possible. He believes in evidence.

Carvaggio: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1601 (look at those faces!)

Two thousand years ago maybe I would have sat next to Thomas and agreed. We might have commiserated together over Christ’s death, grown furious at Judas, sworn silent revenge against Pilate.

No, I’m kidding myself; that’s not how it would have happened at all. To be honest, I probably would not have been within a mile of the Apostles. I don’t know if I would have bought the whole Messiah-come-to-us-in-the-flesh story. I would have held back, curious, watchful, but uncommitted.

Raised Catholic, under the tutelage of nuns and priests in the rigid 50’s and 60’s, I became rebellious, unhappy with the reams of legal requirements thought necessary for acceptance and salvation. I skipped Mass whenever possible; I was part of a guerrilla group of seniors who conspired to hide when Wednesday Mass called the student body to the gym.

Paradoxically, the best class I had in high school was my senior religion class with Mr. Dobrosky, a small, gentle man who tamed us with his honesty. We spent the year in a question and answer tension, exploring the nature of belief and unbelief, the existential response to life and the Christ who lived in the Gospels, not just the one whose maxims had become the dreary, expected backdrop to each day.

I was an atheist for about a week. I had a college course in the philosophy of religion taught by a superb teacher, a charismatic lecturer who also was a militant atheist. His logical assaults on faith, prayer, the afterlife, and the existence of God set me on fire. I had found the truth and it had made me free … to walk out of the classroom and into a purely material world — at which point my imagination conducted its own inquiry: no God equals to nothing beyond rocks and dirt, stars, the chair in which I sit, the glass I hold, and human beings fading slowly into that dirt before my eyes as I spoke to them — nothing but matter alone, atoms alone, just temporarily rearranged. I could not accept that idea. I had seen love and goodness in strangers, and patience and forgiveness. Where did those qualities originate if not in something beyond what I could see? I understood the logical problems with this response; I believed in a spiritual realm in spite of logic, but I also doubted the power of such a realm. I believed in the soul, but my mind and heart remained bound in tension.

For decades I steadfastly avoided churches and their strictures. I found them smothering. I lived my life.

The rise of Christian fundamentalism with its absurd admonitions on evolution, its resolute ignorance about science, its patronizing vision of women, and its embrace of a reactionary politics pushed me farther away from all religious communities.

Then something terrible happened that splintered me. I was put back together by a congregation who did not know me, and yet week after week, month after month, dinners arrived at my door, phone calls ushered me through the nights, Sundays in a light filled sanctuary buoyed me for the week to come.

I began to meet with a minister, a wonderful woman who accompanied me through my reading of the entire Bible and who never pulled back from all my fierce questions. All during this time, the congregation remained faithful to me, a quiet insurgent in their midst, and their kindnesses continued, genuine and offered without equivocation.

I came to love the Christ of Mark’s Gospel. I thought His parables marvelous stories, compressed vignettes full of subtleties that unfolded like complex origami sculptures. I loved the drama of his full epiphany regarding his divinity — standing with that wild man, John the Baptist, in the Jordan, the sky opening, the voice of God appearing suddenly: “You are my beloved son …. (Mark: 1:11).”

I was struck by the many reports of his healing. Among those, He cured a leper, restored a “withered hand,” raised the daughter of Jairus from the dead, mended the sight of blind Bartimaeus, a beggar, gave back motion to the paralytic lowered through the ceiling. He placed Himself among the sick, in the middle of their stench and pus and physical agony. He was able to still their terrible cries. My own experience prepared me to be fixed to His. I could not come away from those accounts without being changed.

His own agony gave His divinity its humanity — at Gethsemane He “began to be greatly distressed and troubled.” He cries out: My soul is very sorrowful, even to death.” Overcome by what is to come, He collapses “on the ground (Mark: 14: 33-35).” He asks that this cup pass from Him. Then, burning with pain on the cross, gasping for air, He has enough patience to listen to the thieves on either side and promise to take the one who defended him to Paradise that day (Luke 23:43). I cannot separate my love from my admiration for Him.

And yet … I have serious questions for Him: Explain progeria to me. Tell me about American slavery, where the slave-master’s cruelty so often walked arm-in-arm with a recitation of the Word? What of the Holocaust and the murder of millions of innocents — children lined up along ditches, crying, waiting for the bullet? What about those children I taught who never had a chance, whose lives were stunted by poverty and neglect or abuse before they could defend themselves? I cannot accept the answer that God has His own plan that we cannot understand. I understand well enough that the innocent should not be preyed upon.

And yet … I have serious questions for Him: Explain progeria to me. Tell me about American slavery, where the slave-master’s cruelty so often walked arm-in-arm with a recitation of the Word? What of the Holocaust and the murder of millions of innocents — children lined up along ditches, crying, waiting for the bullet? What about those children I taught who never had a chance, whose lives were stunted by poverty and neglect or abuse before they could defend themselves? I cannot accept the answer that God has His own plan that we cannot understand. I understand well enough that the innocent should not be preyed upon.

William Blake: God Answering Job from the Whilrwind

But if I have questions about the murder of the innocent, then I must also acknowledge those who are rescued, those who recover, those whom justice redeems.

There is no end to the ambiguity of all this. At the same time I wish to pose these questions I am reminded of a few of Yahweh’s answers delivered out of the whirlwind to Job’s questions: “Who can number the clouds by wisdom (Job: 38: 37); … Do you give the horse his might (39:19); … Is it by your understanding that the hawk soars and spreads his wings toward the south (39: 26)?” … Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth (38:4)?” I know so little, but I cannot make still my mind or my questions. However, I do understand the leap of faith. No logic will carry me to belief so instead each day I try to honor the agents of God whose kindnesses unlocked my unbelief. My attempts to do so are lined with armies of failures, but I think the struggle counts for something, maybe for everything. Therefore, I say, in spite of my doubts, I believe.