Can you caper? Can you bop? How many shimmies and shakes does your body have?

Can you caper? Can you bop? How many shimmies and shakes does your body have?

Stand up. Begin with your neck, the first synovial joint, one that moves in more than one direction. Rotate it. Nod up and down. Nod east to west and west to east. Bounce it, heavy metal style. Tilt it. Shake it up and down while moving it from side to side. Those moves alone add up to six.

Add your shoulder joints and all they can show of arm movements — now add the elbow joints, the wrist joints, the fingers, the sliding muscles of your palms, the slick tendons of your hands.

You can twist and bow from the waist. The ways you can shake your be-hind are legion. Go down. Lean back. The hip bones are connected to the knee bones, the knee bones to the ankle bones. How many rotations in your feet and toes?

In how many rhythms and tempos, cadences and measures, pulses and beats can you shake that whole mo-bile thang?

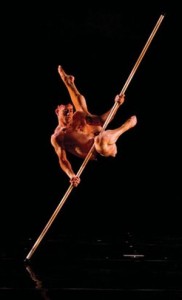

We saw the dance Botanica performed by the Momix Company at the Joyce Theater by 11 dancers, 5 men and 6 women. I think they used every joint and every muscle, all 650 plus, to describe landscapes and seasons, flowers and animals. For 90 minutes without pause, each scene succeeded the next. I think there were over 20 but I couldn’t keep track; I was mesmerized by the energy, grace and shape-shifting power of the dancers. I have never seen such strong, agile bodies.

A quotation from Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Intelligence of Flowers served as the organizing method of the evening: The plant strains its whole being in one single plan: to escape above ground from the fatality below; to elude and transgress the dark and weighty law, to free itself, to break the narrow sphere, to invent or invoke wings, to escape as far as possible, to conquer the space wherein fate encloses it, to approach another kingdom, to enter a moving animated world.

A quotation from Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Intelligence of Flowers served as the organizing method of the evening: The plant strains its whole being in one single plan: to escape above ground from the fatality below; to elude and transgress the dark and weighty law, to free itself, to break the narrow sphere, to invent or invoke wings, to escape as far as possible, to conquer the space wherein fate encloses it, to approach another kingdom, to enter a moving animated world.

The company used a mutating series of stage techniques to add context to its dances — strobe lights, long swathes of nylon, a stage illuminated only with a black light, images projected against scrims and music that changed with each dance. We watched waves course back and forth across the stage and then mutate into mountains and then into the faces and bodies of creatures who rose and then disappeared back into the waves.

One dancer became Narcissus, literally mirror-imaged, entranced by her own beauty. Images rose up: insects, a chrysalis, sunflowers, trees, a forest, a whirling dervish. Dancers skittered across the wood, pranced and rolled, legs extended and feet curling and slowly revolving. They leaped and spun, wiggled, marched and then suddenly balanced, unmoving, the sum of their previous movements flitting past them in my mind’s eye even as they remained still. They stretched and pounced; drumming their legs as if muscle and bone could become pistons, they circled the stage barefoot, pounding their feet in an ecstatic rhythm, their faces lit with joy.

One dancer became Narcissus, literally mirror-imaged, entranced by her own beauty. Images rose up: insects, a chrysalis, sunflowers, trees, a forest, a whirling dervish. Dancers skittered across the wood, pranced and rolled, legs extended and feet curling and slowly revolving. They leaped and spun, wiggled, marched and then suddenly balanced, unmoving, the sum of their previous movements flitting past them in my mind’s eye even as they remained still. They stretched and pounced; drumming their legs as if muscle and bone could become pistons, they circled the stage barefoot, pounding their feet in an ecstatic rhythm, their faces lit with joy.

Spellbinding seems like a misleading word. To be bound by an enchantment — in the unyielding rock of this life, how can that be? But create a 90 minute sprint without a break in one’s submersion in dance and spellbinding is exactly the right word to use. This was as close to a dream-like experience that I have had in a theater. Because no one on stage speaks,the audience must rely upon light, music and the images made by shimmering materials and bodies to make meaning. There is no narrative strand, no story based upon the logic of human events. Instead, we were treated to a interlocking series of visions that all evolve from flowers. When I glanced at others in the audience, I saw so many smiling, leaning forward, their faces alight; these moments were joyful and the dancers’ skills made that joy contagious. Botanica