When Samuel, the Amish boy in the movie Witness, entranced, wanders over to the Angel of Mercy statue in Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, the music rises. You know that a motif has been established. The music announces: here it is – pay attention to those who protect the wounded, who reach to assist those unable to help themselves. Ghostlike, the idea suggested by the statue appears in several images in the movie.

When Samuel, the Amish boy in the movie Witness, entranced, wanders over to the Angel of Mercy statue in Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, the music rises. You know that a motif has been established. The music announces: here it is – pay attention to those who protect the wounded, who reach to assist those unable to help themselves. Ghostlike, the idea suggested by the statue appears in several images in the movie.

The statue is a memorial to all those who had once worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad and had given their lives in WW II. All four sides of its base are covered in names, so many that you believe the inscribers may have run out of room.

Thirtieth Street Station occupies a huge space, the length of a football field and topped by 95 foot high ceilings. Perfect for echoes and for hearing the murmurs of conversations of passersby, it is so large that you can look at and listen to others without giving offense. On this Thursday morning, it fills up with people of all colors and dress, all styles of walking and standing; languages other than English drift on the air currents.

This is an obvious space of movement, that life-blood of cities, but also a place for letting go, for being watched. The great echoing chamber is more of a public amphitheater where no one appears to be acting.

Unlike the atriums of malls or office buildings, the emphasis here is on an active waiting – waiting for the sign board to begin flipping its arrivals and departures, waiting for tickets, waiting for coffee, waiting for a friend or business associate to walk into sight. Here you can watch men and women walking in tight circles as they speak on their phones, tapping their feet, glancing at the

stairways that lead to the trains. Everything here says “Move Now. Now!”

Now you move down the escalator and into the car and then into the light, through and under massive steel, stone and cement structures and into North Philadelphia, past Joe Frazier’s gym and narrow 2 story row houses, past abandoned factories, past the block encompassing Deliverance Evangelical Church, the former site of Connie Mack Stadium. Hundreds of feet of ruined buildings rip past, scrolled with graffiti in pastels of pink and yellow, in purple with black outlines – some of the names are suspended above deep drops, and you have to imagine kids somehow floating, perched on dime-thin footholds, one hand holding on and the spray paint can in the other, carefully leaving evidence of their existence.

Miles of truck parks skim along on either side, so many that you wonder that the world is not made of trucks. Parallel to the single beautiful arch of the Tacony Palmyra Bridge, the Rama Tibet advertises its services.

We roll into the kingdom of warehouses now and single story factories. The train is speeding along and the eye cannot keep up. It jumps ahead continually. You register shapes – rectangles and squares, columns and the thin lines of wires of all types, the film of trees, ribbons of canals and streams and rivers. Wetlands spread out over more space along the tracks than you expect. Electric power stanchions bristle with transformers and wires and surround themselves with sliver-edged barbed-wire.

Interstate highways cut swathes hundreds of yards wide through any landscape, but trains barrel through a strip 30 yards wide. Unlike the deadening monotony of the Interstate, a train’s compression of perspective creates a stream of consciousness – image and question bind themselves together almost simultaneously – what was that? What happened there? Who lives here? How did they build that? What lives in that stream, who lives in those homes, what did they make there? Images flash by so fast. Shapes pop up and are gone, are replaced and replaced again, disappear and then are reshaped. If you place your head on the window and look along its line into the land, it feels as if you are moving at light speed through dozens of worlds.

The Futurist painters were wrong about everything except speed. They understood how speed would change every part of civilization – speed liberates stimulation from any ordinary context; it replicates, intensifies, and infinitely varies its effects. Inside the train our bodies hurtle forward at 60 or 70 mph; we do not have to control that speeding machine. We can look and be filled up again and again by the hurtling landscape. Speed is brutal in its destruction of memory. Speed values only a continuous process. It thrusts us forward only into sensation.

Developments appear on the outskirts of cities, gridded-out, their individual homes at this speed seeming precarious, ephemeral, subject to the same forces that laid waste to all those dead factories that circle the urban lands – the Globe Dye Co., the Crane Co., Morey Machines. This is a pitiless landscape, empty of its manufacturing energy and now forming whole eco-systems of decay. This is the realm of black-hole energy.

The factories again – most are 3 or 4 stories tall, their windows knocked out, weeds everywhere and some so wrecked that cement floors and support pillars alone remain. Sunlight shines unobstructed between the floors. I lost count of how many factories– I had numbered something over 50.

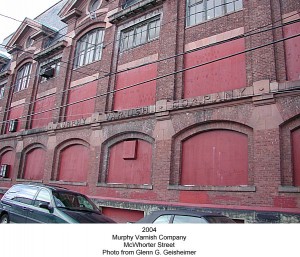

Just south of the Newark, NJ station a monumental ruin stood out over a neighborhood. One formidable smokestack ascended from a brick building whose decorative effects, even from hundreds of yards away, suggested another lifetime of craftsmanship. Triangle arches framed massive windows. Everything around it was of the commonplace world. The structure belonged in a myth.

Just south of the Newark, NJ station a monumental ruin stood out over a neighborhood. One formidable smokestack ascended from a brick building whose decorative effects, even from hundreds of yards away, suggested another lifetime of craftsmanship. Triangle arches framed massive windows. Everything around it was of the commonplace world. The structure belonged in a myth.

I looked and looked and found it – the Murphy Varnish Company, long shuttered, rotting, its long term fate unknown. I do not believe in ghosts, but these places of lost work seem filled with such rage and sadness that they must be haunted.

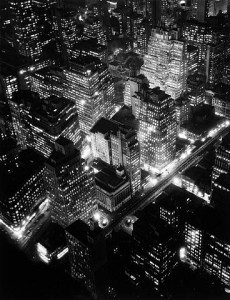

Into Penn Station and then up escalators and into the bright city, whose indifferent, heart-accelerating energy attaches itself to everything, and where nothing could be haunted, at least, not yet.