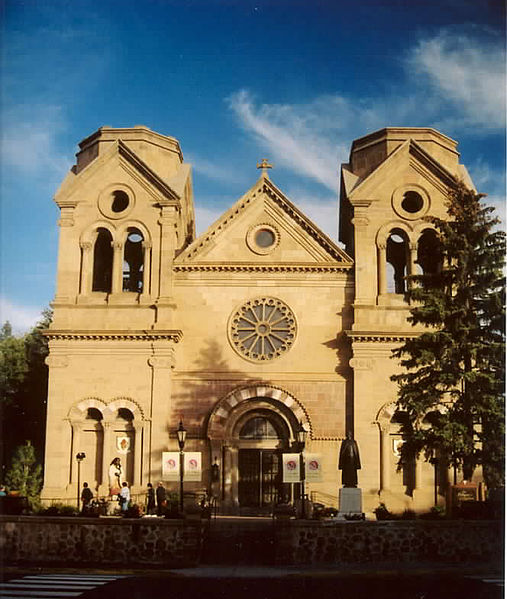

The twin towers of The Basilica of St. Francis are bounded by parks where, in this early spring, the cherry and cottonwood trees have begun to blossom. To the west, just behind the Church, sculptures of the Stations of the Cross form a circle in a small, pleasant, shaded oval. A garden wall separates it from the street. To enter, one must seek out the gate.

The twin towers of The Basilica of St. Francis are bounded by parks where, in this early spring, the cherry and cottonwood trees have begun to blossom. To the west, just behind the Church, sculptures of the Stations of the Cross form a circle in a small, pleasant, shaded oval. A garden wall separates it from the street. To enter, one must seek out the gate.

This is where a short priest in his collar and black shirt, keys resting against his hip, knelt before the statue of Christ on the Cross. He bent his head to its plinth and extended his right hand to cup Christ’s small, bronze foot. He paid no attention to me, not now and not at any of the other Stations whose route he was following. Flecks of sunlight fell on his back and legs.

He remained face down and still for more than a minute. Then … two minutes, a long time to remain publically immobile and silent in this frenetic age. I stood thirty feet away at another Station, acutely aware of the quiet and of this priest’s supplication in prayer.

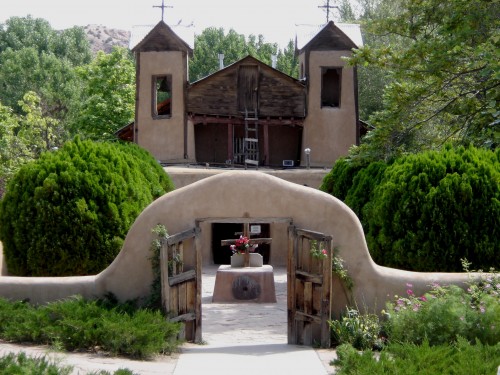

Two days later, on the High Road to Taos, we passed through the old Mission villages of Cordova, Nambe, Truchas and Las Trampas, where the original Mission Church has adobe walls four feet thick and one can run hands over straw from the first mixture laid down four hundred years ago. Each village held its own Church, all of them austere, humble structures that look as if they had arisen continuous and complete from the landscape. At Sancturio de Chimayo a specified mixture of dirt in a bowl in the floor near the altar is said to heal illness and broken bodies.

Miles before we arrived we passed bands of men, women and children walking the pilgrimage road to Chimayo, their red pennants carried above them to warn off cars. Some carried large crosses in both hands. We saw hundreds. The yearly pilgrimage reaches its zenith Easter weekend with Good Friday being especially crowded.

The path leading up to the plaza is paralleled by a fence on which hand-made crucifixes are tied by twine, by grape-vine, by rosary beads. They covered the length of the fence. The Del Ferraro family had made two. Another, constructed out of clothes pins held a small painting of two horses at its center. Below it a cross made of brass contained an engraved portrait, eyes closed, of a very young Virgin Mary adorned in robes.

Over the loud speaker, the tinny voice of the priest saying Mass in the Chapel said, “Pilgrimage is synonymous with sacrifice.” On the back wall of the Chapel, five panels, each 10’ long by 6’ high. Several thousand photographs — more young people than old, more Hispanic than white, more women than men, more smiling than not. The many faces of the beloved dead. On a few, names: Diego Gonzalez, a Marine in dress blues, 27; Gina Anne Marie Benevidez, 19, smiling; Donald “Boogie” Chavez, 43.

In the space across from the panels, an open garden with an altar at its center for the celebration of Mass in good weather. A few feet away, clear, fast-moving water coursed down a narrow channel next to bright green pastures where black cattle rested in the cleft of two high green hills. To the right of the altar, a statue of a man in a wide hat carrying a staff, a bag slung over his shoulders. This inscription in Spanish and English:

Come pilgrims from the four corners of the earth. The Lord has invited us to walk to his shrine of love in Chimayo. There we will find the “holy dirt” that strengthens us and purifies the faith that takes away our pain.”

In the plaza in front of the Church, penitents and tourists sit and stroll. A group of a dozen softly sing a hymn in Spanish in one corner. A man carrying a pit-bull puppy drinks water and ice. Bicyclists in big mustaches and yellow shirts bearing large, red crosses rest in the shade of the trees. When we leave, we pass large groups of pilgrims walking through the parking lot, nuns in sneakers among them.

We are following a road marked by churches through a high desert landscape marked by steep gorges, mesas and at the higher elevations, hills clothed in pine trees. How did priests find their way to these places and then endure in this wilderness with their certainties unbroken?

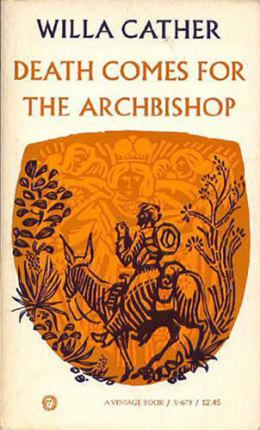

From an essential novel about New Mexico, Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather:

He had, indeed, for years, directed the thoughts of the young priests whom he instructed to the fortitude and devotion of those first missionaries, the Spanish friars; declaring that his own life, when he first came to New Mexico, was one of ease and comfort compared with theirs. If he had used to be abroad for weeks together on short rations, sleeping in the open, unable to keep his body clean, at least he had the sense of being in a friendly world, where by every man’s fireside a welcome awaited him.

But the Spanish Fathers who came up to Zuñi, then went north to the Navajos, west to the Hopis, east to all the pueblos scattered between Albuquerque and Taos, they came into a hostile country, carrying little provisionment but their breviary and crucifix. When their mules were stolen by Indians, as often happened, they proceeded on foot, without a change of raiment, without food or water. A European could scarcely imagine such hardships. The old countries were worn to the shape of human life, made into an investiture, a sort of second body, for man. There the wild herbs and the wild fruits and the forest fungi were edible. The streams were sweet water, the trees afforded shade and shelter. But in the alkali deserts the water holes were poisonous, and the vegetation offered nothing to a starving man. Everything was dry, prickly, sharp; Spanish bayonet, juniper, greasewood, cactus; the lizard, the rattlesnake,–and man made cruel by a cruel life. Those early missionaries threw themselves naked upon the hard heart of a country that was calculated to try the endurance of giants. They thirsted in its deserts, starved among its rocks, climbed up and down its terrible canyons on stone-bruised feet, broke long fasts by unclean and repugnant food. Surely these endured Hunger, Thirst, Cold, Nakedness, of a kind beyond any conception St. Paul and his brethren could have had. Whatever the early Christians suffered, it all happened in that safe little Mediterranean world, amid the old manners, the old landmarks. If they endured martyrdom, they died among their brethren, their relics were piously preserved, their names lived in the mouths of holy men (275-276).

But the Spanish Fathers who came up to Zuñi, then went north to the Navajos, west to the Hopis, east to all the pueblos scattered between Albuquerque and Taos, they came into a hostile country, carrying little provisionment but their breviary and crucifix. When their mules were stolen by Indians, as often happened, they proceeded on foot, without a change of raiment, without food or water. A European could scarcely imagine such hardships. The old countries were worn to the shape of human life, made into an investiture, a sort of second body, for man. There the wild herbs and the wild fruits and the forest fungi were edible. The streams were sweet water, the trees afforded shade and shelter. But in the alkali deserts the water holes were poisonous, and the vegetation offered nothing to a starving man. Everything was dry, prickly, sharp; Spanish bayonet, juniper, greasewood, cactus; the lizard, the rattlesnake,–and man made cruel by a cruel life. Those early missionaries threw themselves naked upon the hard heart of a country that was calculated to try the endurance of giants. They thirsted in its deserts, starved among its rocks, climbed up and down its terrible canyons on stone-bruised feet, broke long fasts by unclean and repugnant food. Surely these endured Hunger, Thirst, Cold, Nakedness, of a kind beyond any conception St. Paul and his brethren could have had. Whatever the early Christians suffered, it all happened in that safe little Mediterranean world, amid the old manners, the old landmarks. If they endured martyrdom, they died among their brethren, their relics were piously preserved, their names lived in the mouths of holy men (275-276).

Faith here feels more physical than doctrinal – bodies at work hauling mud in baskets up ladders to thicken adobe walls; priests on donkeys traveling hundreds of miles in cold, snow and heat to perform marriages, baptize children, say Mass in Churches with newly whitewashed walls, heated by pinyon wood. And now, sweating walkers on long stretches of sun-drenched highways; men with big shoulders and arms and old women on their knees in gravel, heads bowed, lips moving.

We always attended school on Good Friday. Two by two we filed to Mass in the morning. I remember walking thus under one mythic spring sky, turning over and over with dark clouds and light. Our fifth grade teacher, Sister Francis Marian, told us that at the moment of Christ’s death, at 3:00 P.M. precisely, enormous black clouds raced across the sky above Golgotha, a wind blew hard and the curtain in the Temple ripped apart down the center as if torn by invisible hands.

On the High Road to Taos I kept returning to that memory and to the image of the young priest, deep inside his devotions among the Stations of the Cross at St. Francis. These thoughts about the spirit, about Christ on that desert hill, about the essential nature of belief, come so easily at this dry meridian and under this imperial sky, the deepest blue I have ever seen.

Lovely depiction of impressions of the landscape and what it evokes in those who visit for the first time.