Driving south from the Little Big Horn Battlefield into Wyoming, through Ranchester and Sheridan, skating past the Tongue River and Dayton, we began to climb through the Big Horn Mountains. We cut up through switchbacks, through escarpments, past synclines opened to our view by road cuts, higher and higher to a view of hundreds of miles of gold land and maroon shadows and ribbons of green where streams moved past small towns.

Postmarked along the roadside were markers that described each geological era we passed. We rose through the Pennsylvanian, 280 million years ago, through the Devonian, 360 million, through the Ordovician, 450 million. At 7000 feet we saw a flock of migrating robins hurrying south. Up through the Precambrian, 2.5 Billion years ago, and at 9000 feet we pulled into Sibley Dam and Lake, a 1937 CCC project built by Company 653 of Texas men. Three or four young women were painting the observation decks in preparation for the winter. Their exuberant laughter mixed with the calls of a resident osprey and kingfisher, and coming together their laughter and those pure Osprey screams and Kingfisher cracklings seemed to fit. Maybe all of us were giddy with altitude. We walked the circumference of the lake and up the mountain trail smiling, just shod animals for a little while. The sound of the wind in the pines, that inimitable swishing push of air, swept up all around us as we walked.

Frank Bergon* once spoke of mountain fever, by which he meant the ardor that pushed one to climb higher, to see the world unrolled like a vast document, one that you are happily desperate to read, and then to rejoice in the hot-blooded physicality of standing above clouds. On our last night as a class, full and pleasantly exhausted after a long hike with heavy packs, knowing that all of us were flying out and away from high peaks in the next day or so, he said that we would always know that the mountains were waiting for us. No matter how long we stayed away, no matter the quality of the lowlands where most of us lived, we would remember walking among and climbing these mountains, under this blue sky like no other, and in surprising ways, those memories would sustain us. He was right. Thirty years before, and more, I had walked and climbed through the Rockies in Montana, Wyoming and Colorado. I was full of young-man-spit and grit, and I had reveled in a landscape I had never seen. I had been back only once and only for only four days at Estes Park in Colorado on my honeymoon.

But I was 59 now, not 29 and walking in the the mountains on this trip brought another effect besides an astonished sense of well being and vigor. I could not move as I had moved then. I remembered a skylarking, smooth, greased-rail kind of glide up trails and scree slopes and on traverses across avalanche tracks. Now I walked slowly and was sometimes short of breath. A voice inside, which I tried to ignore, whispered cautious advice; “Stop. Sit. Drink more water. Rest against this rock.” Age creeps along. When I had once thought of mountains outlasting me, I merely paid it intellectual lip-service: “Ah yes, they are very old. Geology is interesting. I remember my terrific undergrad course.” My immortality had been in full bloom. Now I can feel what is coming and thus the mountains provoke a more meditative response and perhaps one tinged with envy.

This is one way in which mountains have changed for me. Perhaps they have become a mute sign of the limits of time for me, an empheral, transitory creature.

When I walked out of the Relocation Museum, I looked up at the massive block of Heart Mountain, 355 million years old and composed of limestone and dolomite. It has such a distinctive shape that it fits easily into the memory. The Relocation Camp held about 11,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry who arrived beginning in 1942. FDR ordered them detained after Pearl Harbor. They remained there until late 1945. When they finally scattered across the United States upon their release, they received a bus ticket and $25. Their jobs, businesses and homes had vanished from their lives. Very few recouped their losses.

The politics of that detention are complicated. They still have the power to inflame, particularly in light of our national struggle over Islam, Muslims, Mexicans, immigrants as a whole. For a moment, forget all of the politics and think of them as human beings who were powerless to leave but able to look out and up at this figure that remained a constant mark of their place and time.

They left the camp as they arrived, with a suitcase or two each. Some of them packed stunning calligraphies of Heart Mountain, the icon of their confinement. In the best of these images the Mountain seems often to have been composed of two or three precisely right strokes of ink. It hovers over the camp, light as snowfall, reflecting sunlight, catching moonlight, seen in first light and then back-lit by sunset, always there.

Heart Mountain, outside of Cody, rising above the site of the Relocation center for Japanese-American detainees in WW II

The Mountain becomes a memorial in these pictures, a marker retained within their memories of a cold and terribly hot, sun-swept, closely watched period of their lives. In November of ’45 when they climbed onto those busses, they took this image of the Mountain with them. At our final campfire Bergon said that the mountains would stay with us. In our high spirits and in the glaze of our 20’s, in the impatience and speed of our sensibilities, we thought only of ecstatic moments high above timberline looking out at a landscape as endless as our youth seemed to be. The images created by the Nisei of Heart Mountain acknowledge an older kind of appreciation — they grew to know this Mountain in all its shape-shifting lights. They acknowledged a beauty that was both ancient and mutable and yet as captives, working against this peace, a part of them had to have been filled with uncertainty and a sense that their time behind barbed wire and watchtowers would only go on and on, and that their lives were rushing past them somewhere outside the gate. Maybe their images also capture this perspective, for in many of them, the rows of barracks and the wire stretches out to the edge of the paper.

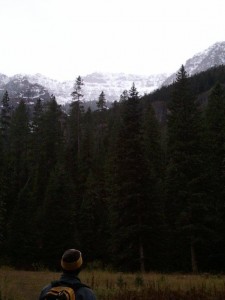

On a gray, rainy day in Bozeman we drove to the beginning of the Hyalite Trail, one that I had last seen 34 years before. Then I had been with my grad class from Montana State University. We had crossed the pass and camped at the foot of Hyalite Mountain and early the next morning, alone, I had climbed to the saddle and then to the peak. I remember sitting on the top and being filled with a profound quiet, a sense of peace, the consolation of high places.

Now we climbed to Grotto Falls through stands of Douglas Fir. It grew increasingly cold as we switchbacked up. The snow cover on the peaks shining through the pass far above us grew clearer. Snow showers blew over the pass. It was not possible to go on. We lacked the gear and clothing, and it was too late in the day. No one else was on the trail. I wanted to go on. I wanted to cross the pass and climb to the saddle and glide patiently up those last 300 feet or so to the peak … but not out of nostalgia. Moments can never be inhabited again. No, I wanted to walk up through that light because we were present in the moment, and I wanted that happiness to also go on and on.

*a writer and professor who I was fortunate enough to have caught as a teacher for one of my wilderness literature courses — this one in the San Juan Mountains outside of Durango in southwestern Colorado