Four more carted home yesterday afternoon, their silent promise the oldest continuous expectation of happiness in my life, and I had to stop and pick up one more reserved for me at the library, and then merrily away with a biography of Mozart and Jerusalem, two novels about desperate times in the South and one piece of reporting about returning veterans and the lives they struggle to restore. Meanwhile, I’m ninety pages into my second reading of Ulysses, midway through a collection of Heaney, the order for two more Roth novels has been placed, and another half-dozen titles have nestled into my anticipation. I must catch up. In fifty years I will catch up. I know that I will never catch up.

Four more carted home yesterday afternoon, their silent promise the oldest continuous expectation of happiness in my life, and I had to stop and pick up one more reserved for me at the library, and then merrily away with a biography of Mozart and Jerusalem, two novels about desperate times in the South and one piece of reporting about returning veterans and the lives they struggle to restore. Meanwhile, I’m ninety pages into my second reading of Ulysses, midway through a collection of Heaney, the order for two more Roth novels has been placed, and another half-dozen titles have nestled into my anticipation. I must catch up. In fifty years I will catch up. I know that I will never catch up.

One of my earliest memories is of a book. I have no idea of its title or who held it – an adult hand, that’s all I can see of the person. I don’t know how old I was or the place where I saw it. The book was thick, hardcover, and when the hands opened it, bright images of men on horses, battle scenes I think, filled up my gaze.

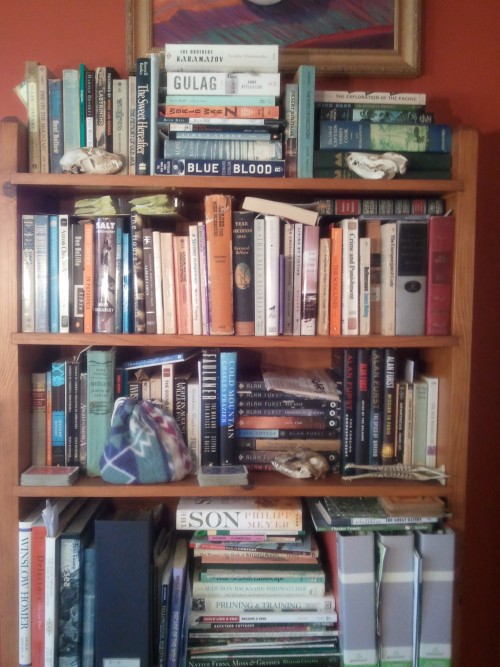

Women read to me – aunts, nuns, my mother, but I was also reading by 4 or 5, and I have had books near me ever since. I’ve owned thousands and thousands of them, and have sent them off and restocked them in a kind of comic addiction, sometimes donating a title I thought I had been finished with only to have another run of curiosity about it cause me to later put more dollars down to take it home again.

Women read to me – aunts, nuns, my mother, but I was also reading by 4 or 5, and I have had books near me ever since. I’ve owned thousands and thousands of them, and have sent them off and restocked them in a kind of comic addiction, sometimes donating a title I thought I had been finished with only to have another run of curiosity about it cause me to later put more dollars down to take it home again.

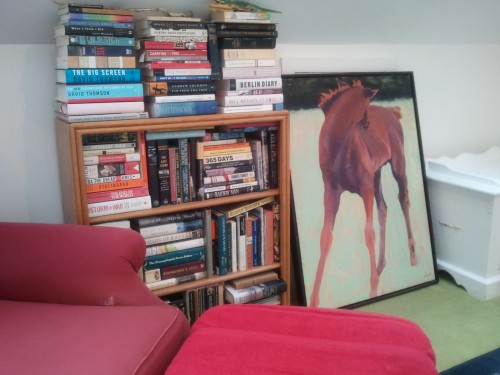

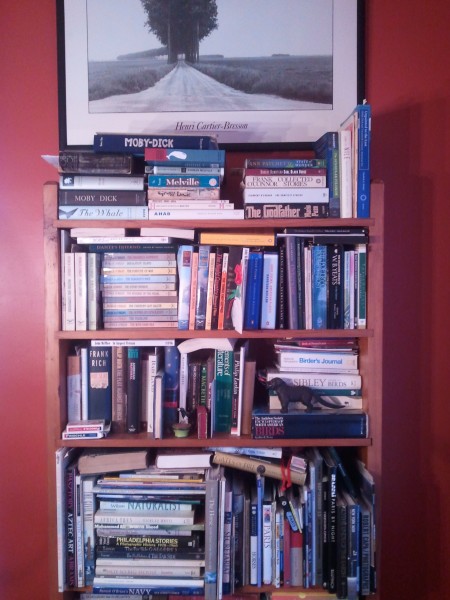

I like the bulk and texture of books, their fusty smells and the sight of print on white pages, their practicality and ease of use, their splendid covers, which are gestures in themselves, and their titles arrayed in every type of font. Before I read I look and lift, and the pre-language properties of those actions also delights.

Two book cases, each seven and a half feet tall and made of good hardwood, sanded and varnished a dark auburn color by my father and brother-in-law, rest on either side of our kitchen table. I look at them dozens of times a day, and on their shelves, at hundreds of titles whose positions I know by heart, tumbled now but periodically sifted and made to look straight and trim. My father inhabits those shelves; he made them for me.

Memory makes us who we are, and in my kingdom of books I remember buying Gravity’s Rainbow in a tiny book store in Kutztown in 1974, putting aside all my other course work, and reading all 700+ pages in a few days. I remember sitting in the rounded, windowed tower of a Reading apartment late at night and reading Bruce Catton and Shelby Foote’s trilogies on the Civil War. I remember shoving paperbacks into my pack for my trip to the British Isles and being amused that one of them was a biography of Babe Ruth. I remember leaning over a desk in a back room of an old home late, very late; snow had been falling all night. My desk lamp alone was lit. I kept poring over one of Hamlet’s soliloquies, trying to understand it, playing and rewinding a Caedmon audio tape of the play, listening to Paul Scofield say it again and again while I read the text, and then a line opened up and like beautiful horses slowly passing me, all of the lines came together as if alive and made sense, and I remember turning off the light and looking at the snow and being very happy.

If my life has had two imperatives, they are these: I must move, and I must read. I cannot be still for very long. I cannot be without a book. So — I work, I walk, I lift and set down, I sweat. Then I read. I must labor, and then I may rest, pick up a book and dream in other lives. If they could, my wonderful aunts and the good nuns who taught me would shake their heads and smile in acknowledgment of their powerful lessons.

If my life has had two imperatives, they are these: I must move, and I must read. I cannot be still for very long. I cannot be without a book. So — I work, I walk, I lift and set down, I sweat. Then I read. I must labor, and then I may rest, pick up a book and dream in other lives. If they could, my wonderful aunts and the good nuns who taught me would shake their heads and smile in acknowledgment of their powerful lessons.

Whenever I visit someone’s home for the first time, nothing interests me more than their collection of books. Especially if they’re all crammed and heaped together like this. It’s a good look.