Walk 25 yards north from the house and you enter a pasture open to this Autumn’s wide blue sky. Pause now, back to the house, and close your eyes. Conjure your powers of

Walk 25 yards north from the house and you enter a pasture open to this Autumn’s wide blue sky. Pause now, back to the house, and close your eyes. Conjure your powers of  banishment. Imagine yourself an exile from 2012. Banish the lawnmowers and leaf-blowers shuddering close-by. Banish the streaming traffic from Holmes Road. Make it a dirt road. Now you can hear the wind. Now you can hear yourself think. In their Autumn of 1850, Herman Melville and his family had 10 straight days of blue skies and fiery leaves — a good omen.

banishment. Imagine yourself an exile from 2012. Banish the lawnmowers and leaf-blowers shuddering close-by. Banish the streaming traffic from Holmes Road. Make it a dirt road. Now you can hear the wind. Now you can hear yourself think. In their Autumn of 1850, Herman Melville and his family had 10 straight days of blue skies and fiery leaves — a good omen.

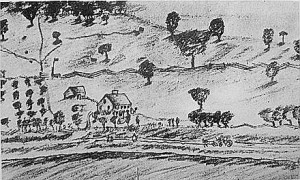

Melville’s drawing of Arrowhead from memory in 1861

Arrowhead is a large house; the extended wing off the back has plenty of bedrooms for all the people who lived there in the winter of 1850-1851  when Melville was writing Moby Dick: his wife, a child, two unmarried sisters, his mother and three servants. He had also hired an extra hand to help him farm about 30 of the 160 acres he owned. It looks as if his closest neighbor would have been about a mile away, but he wasn’t lonely. He had met Nathanial Hawthorne, old enough to serve as a surrogate father, and a writer who also explored dangerous places; Hawthorne’s friendship seems to have been one of the provocations that pushed Melville toward a deepening of Moby Dick. He admired him so much that he dedicated the novel to him. He must have believed that everything was coming together; that all his sails had now blossomed with a fair wind. He had escaped New York City, his books had made some money, his first born child, a son, was only three months old so a baby enlivened all their lives, and he and his wife, Lizzie, were “two such happy hearts (257).”@ He was 31, a young man passing into his prime, and he thought himself possessed of a story that he felt sure would make his name.

when Melville was writing Moby Dick: his wife, a child, two unmarried sisters, his mother and three servants. He had also hired an extra hand to help him farm about 30 of the 160 acres he owned. It looks as if his closest neighbor would have been about a mile away, but he wasn’t lonely. He had met Nathanial Hawthorne, old enough to serve as a surrogate father, and a writer who also explored dangerous places; Hawthorne’s friendship seems to have been one of the provocations that pushed Melville toward a deepening of Moby Dick. He admired him so much that he dedicated the novel to him. He must have believed that everything was coming together; that all his sails had now blossomed with a fair wind. He had escaped New York City, his books had made some money, his first born child, a son, was only three months old so a baby enlivened all their lives, and he and his wife, Lizzie, were “two such happy hearts (257).”@ He was 31, a young man passing into his prime, and he thought himself possessed of a story that he felt sure would make his name.

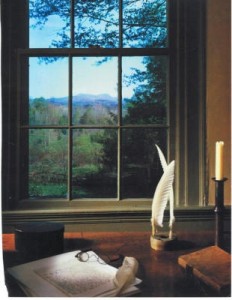

The part of the house facing Holmes Road had originally been a tavern; it housed a kitchen with an enormous fireplace, a dining room and a front parlor. These are dark spaces; they would have been cozy at night with a fire going. Climb the staircase though and light fills the front rooms. The bedroom is large and faces south and east; Melville could walk across the landing and into his study where he did his writing. He sat at a table in the middle of the room, positioned so that he could look through the north facing window to Mt. Greylock, the highest point in Massachusetts and dominated by double humps like the whale he was struggling to bring to life. He could shut the doors and write; the fireplace behind him would have kept off the chill. He would have heard the murmur of a busy household, a sound more comforting and more conducive to work than absolute silence I think.

The part of the house facing Holmes Road had originally been a tavern; it housed a kitchen with an enormous fireplace, a dining room and a front parlor. These are dark spaces; they would have been cozy at night with a fire going. Climb the staircase though and light fills the front rooms. The bedroom is large and faces south and east; Melville could walk across the landing and into his study where he did his writing. He sat at a table in the middle of the room, positioned so that he could look through the north facing window to Mt. Greylock, the highest point in Massachusetts and dominated by double humps like the whale he was struggling to bring to life. He could shut the doors and write; the fireplace behind him would have kept off the chill. He would have heard the murmur of a busy household, a sound more comforting and more conducive to work than absolute silence I think.

He wrote from about 9 to 2:30, responded to the knocking at his door, left his desk to attend to farm chores, and then rigged his horse Charlie  to the sleigh and with his mother and sisters# rode into Lenox to greet friends or go to the library.

to the sleigh and with his mother and sisters# rode into Lenox to greet friends or go to the library.

I have to believe that he probably cut his share of the wood needed to heat such a rambling house. It is hard not to imagine him doing so – his mind wandering through the rhythm of the ax-work, more ideas coming to him, more images appearing, his body coming to life again in the cold after hours hunched up and closed off.

His wife and sisters would recopy his day’s work and read it to him at night. In his “mesmeric state”# he would make changes to his sentences guided by his ear.

That winter his talent was as close to perfect as it would ever be in his life. His romance about the ‘whale fisheries’ had become something more profound and daring, and his creative powers were so intense that “at times Melville felt that no mortal pen could possibly transcribe the thoughts that were teeming through his brain (261).”@ He wrote that “a Polar wind blows through it, & birds of prey hover over it.”#*

That winter his talent was as close to perfect as it would ever be in his life. His romance about the ‘whale fisheries’ had become something more profound and daring, and his creative powers were so intense that “at times Melville felt that no mortal pen could possibly transcribe the thoughts that were teeming through his brain (261).”@ He wrote that “a Polar wind blows through it, & birds of prey hover over it.”#*

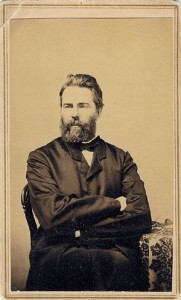

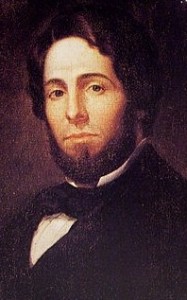

Melville in 1860

From 1839 to late 1844 he seems to have been in continual motion. He was only 19 when he went to sea on a merchantman bound for Liverpool. In the  next 5 years he came to know every kind of grand water – the North Atlantic, the Mississippi, the South Atlantic and the Pacific. He sailed on whalers and a US Navy Frigate. He lived with cannibals in the Marshall Islands, with ner’do wells on Tahiti, and with seamen of every nationality and language. He climbed the rigging in all weathers, traveled round Cape Horn, endured terrible storms, helped kill and process whales, visited islands so far removed geographically and culturally from his roots as to have been on a another planet circling another star. He seemed to have remembered everything.

next 5 years he came to know every kind of grand water – the North Atlantic, the Mississippi, the South Atlantic and the Pacific. He sailed on whalers and a US Navy Frigate. He lived with cannibals in the Marshall Islands, with ner’do wells on Tahiti, and with seamen of every nationality and language. He climbed the rigging in all weathers, traveled round Cape Horn, endured terrible storms, helped kill and process whales, visited islands so far removed geographically and culturally from his roots as to have been on a another planet circling another star. He seemed to have remembered everything.

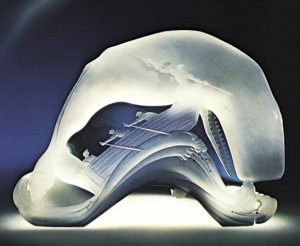

Moby Dick in Steuben Crystal by Donald Pollard, 1959

But all his hopes went sour. Moby Dick did not sell. The reviews were contemptuous. Unsold copies disappeared in a warehouse fire. Hawthorne turned away from him. Jobs he had hoped for never materialized. He sold Arrowhead in 1863 and returned to New York City. He turned increasingly silent and angry. Many thought him on the edge of insanity, as if he had come to inhabit Ahab himself, as if Ahab’s question of Perth had become his question to himself: “How can’st thou endure without being mad (699).”* His wife grew afraid of him. His two boys died. He broke down the door of a room in his own home and found his first born son dead of a gunshot. He finally secured a job as a customs inspector, a clerk often nailed to a desk. Perhaps he sometimes rowed from ship to ship in New York harbor, inspecting cargoes, applying tax stamps, his last years on the water a terrible caricature of his glorious years of adventure. When he died in 1891, the New York Times obituary offered that, “he [had] died an absolutely forgotten man.” ** Not quite. The first glimmerings of a resurrection arrived immediately after his death: “Certainly it is hard to find a more wonderful book than this Moby Dick, and it ought to be read by this generation, amid whose feeble mental food, furnished by the small realists and fantasts of the day, it would appear as Hercules among the pygmies, or as Moby Dick himself among a school of minnows.” *** He was rediscovered in the 1920’s; Moby Dick became among the most honored of books of world literature.

The acclaim and money came thirty years too late. That is the tragedy of well-earned praise arriving after all need for it is gone; the tragedy of a life at least partially blighted by having written something meant for the next century. There is too much sadness in his life, but it does not seem accurate to end on such a note. Better to remember men and women in their strength, eyes fully ablaze. Moby Dick now has its splendid immortality. One hundred and twelve years ago he had this winter of peace and happiness, and he made this haunted, sublime book.

The acclaim and money came thirty years too late. That is the tragedy of well-earned praise arriving after all need for it is gone; the tragedy of a life at least partially blighted by having written something meant for the next century. There is too much sadness in his life, but it does not seem accurate to end on such a note. Better to remember men and women in their strength, eyes fully ablaze. Moby Dick now has its splendid immortality. One hundred and twelve years ago he had this winter of peace and happiness, and he made this haunted, sublime book.

Melville as a young man: portrait by Asa Twitchell

I ended my time at Arrowhead eating almonds and an apple on a bench fifty feet away from where Melville had written the novel that I love so much. I suppose pilgrimages are meant to be suffused by piety and by a longing for mystic connections, a trance, maybe a revelation. I felt giddy and happy.

suppose pilgrimages are meant to be suffused by piety and by a longing for mystic connections, a trance, maybe a revelation. I felt giddy and happy.

A first edition of Moby Dick

I want to think of Melville in his “ship’s cabin”# of a study coming up out of his imagination, noticing the candles guttering in the draft, raising his head from his tight handwriting, and looking out through the frosted window north to Mount Greylock, white and yellow in the late sun. Even with “snow drifts piling up to the first floor windowsill (261),”@ his dream-state is so persistent that he can still sense the “air transparently pure and soft,” and the “all-pervading azure of air and sea (774).”* He can still hear Ahab’s long final lament to Starbuck. He can still see the White Whale rising in blue water under a warm sun.

#Letter to Evert Duyckinck, December 13, 1850

#Letter to Evert Duyckinck, December 13, 1850

@Melville: A Biography by Laurie Robertson-Lorant

#*Letter to Sarah Morewood, September ?, 1851

**The New York Times, October 2, 1891

***The Springfield Massachusetts Republican, October 2, 1891

* Moby Dick Or The Whale by Herman Melville: Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. Random House: New York, 1930.