Love appears, like some kind of Genesis event, out of nothing. We do not choose those with whom we fall in love. I do not know precisely how it begins to happen, but there is always some style in the catalyst – the sympathy of another’s eyes, the saunter or stride of a walk, a pleasing laugh, an insightful remark. Then we cartwheel into our affection for them, our chemistry goes boom-de-boom, and the irrevocable mark has been made upon us.

Love appears, like some kind of Genesis event, out of nothing. We do not choose those with whom we fall in love. I do not know precisely how it begins to happen, but there is always some style in the catalyst – the sympathy of another’s eyes, the saunter or stride of a walk, a pleasing laugh, an insightful remark. Then we cartwheel into our affection for them, our chemistry goes boom-de-boom, and the irrevocable mark has been made upon us.

We fall in love with men and women, but we never stop there. We fall in love with dogs and horses, with houses and cities, with  paintings and trees and oceans and boats and cars and mountains. I can’t speak to the intensity of such connections; that is too singular a relationship to measure. I can say that we don’t divorce these paramours; they stay with us to the end, there’s or ours, and we never forget the first time we saw them.

paintings and trees and oceans and boats and cars and mountains. I can’t speak to the intensity of such connections; that is too singular a relationship to measure. I can say that we don’t divorce these paramours; they stay with us to the end, there’s or ours, and we never forget the first time we saw them.

I fell in love with books and stories and did so because my family loved them with me and my father and mother loved them before me. Everyone read in our house. We read at the breakfast table, we read before going to sleep, we read on rainy days — we built stacks of books in our bedrooms where they balanced on nightstands and shelves.

When I was 12, my older sister walked with me to the local high school on a fall night. Its library had been opened to the community. The stacks stretched on and on and were much taller than me. I had already fallen for books, for everything about them – their crackle and scent, their weight, how they cradled in my hands, the look of print on the page – ordered, progressive, one page giving itself up to another and another. When I found a book that held me, I would sweep the pages I had not read, catching them and flicking my thumb along their edges, delighted that there was still so much left to be revealed.

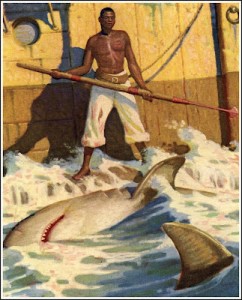

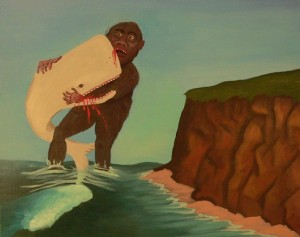

Queequeeg Killing the Sharks: Mead Schaeffer

Queequeeg Killing the Sharks: Mead Schaeffer

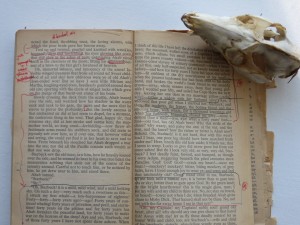

On this night I trailed behind Annette, vacant, brushing the spines of books with my right hand, pausing before titles and designs that caught my eye, pulling them off, opening them at random, pushing them back in, and trying not to bother my older sister. I saw a large book with blue and gold colors on the spine. It took both my hands to bring it down. I opened it randomly to a full page illustration of a dark man with tattoos on his face standing on a thin board attached to a ship. He held a kind of spear in his hands. Below him a confused mass of sharks rose from the sea on each other’s backs, mouths open and filled with teeth. The tattooed man was thrusting his spear into the sharks. I looked at the blood on the blade and the swirling sharks inches from his feet. I sensed his calm in the middle of a nightmare. I remember thinking that the picture was moving; it was static but it was moving. I asked my sister to bring this book home.

my eye, pulling them off, opening them at random, pushing them back in, and trying not to bother my older sister. I saw a large book with blue and gold colors on the spine. It took both my hands to bring it down. I opened it randomly to a full page illustration of a dark man with tattoos on his face standing on a thin board attached to a ship. He held a kind of spear in his hands. Below him a confused mass of sharks rose from the sea on each other’s backs, mouths open and filled with teeth. The tattooed man was thrusting his spear into the sharks. I looked at the blood on the blade and the swirling sharks inches from his feet. I sensed his calm in the middle of a nightmare. I remember thinking that the picture was moving; it was static but it was moving. I asked my sister to bring this book home.

The Spirit Spout: George Klauba

That image of Queequeg killing the sharks introduced me to Moby Dick; I read the novel for the first time when I was twelve, and I read it as a boy’s adventure book. I skipped chapters, devoured the illustrations, and stayed with the chase. I loved the gothic eeriness of the Pequod and the madness showing in Ahab’s face — bone-thin, skull-showing, laced with that wonderful-awful white scar. I loved the pictures of the white whale, harpoons studding his back, his eye a red center in all that white, the sea filled with cracked, sharded boats and men desperate in the water. It was heaven. I was twelve and in love. I have lost count of how many times I have read the book since then. I taught it to eight or nine senior AP and College Prep classes, and in an act of hubris, one honors ninth grade class.

I have had students argue that Moby Dick is an antique, a relic, that it is dull, indigestible, endless, a skeleton uselessly moaning “Hast thou seen the White Whale” – that it should be removed from high school curriculums, that it proves that ‘best of’ lists are compiled by fusty old men in small rooms far away from contemporary life, that it has long passed its usefulness as a commentary on how we live.

A 1902 photograph of a Sperm Whale being rendered.

A 1902 photograph of a Sperm Whale being rendered.

I would argue that Moby Dick is a dispatch from what Griel Marcus called our “old, weird America”. It comes from a time when the continent was virtually empty (1850 census = 23 million), when most of the population labored on solitary farms which had to be wrenched out of woods and prairie, when wilderness was the norm, not the rarity it has become, when wild animals were subject to explanations based more on myth and story than on science, when religion and the Bible were fundamental influences in our cultural life, when the Origin of the Species was still eight years from publication, when we could not fly, send signals through the air, when genetics was not even a word, when 3 million human being were consigned to slavery, when we were inching toward a terrible civil war, when we were sending thousands of men in ships on long, secluded voyages to kill whales in intimate, dangerous, blood-drenched fights and then flay them and boil them down into a product. The only whalers we see today are pursued by Greenpeace in a reality television show, and they are portrayed as villains engaged in the killing of sentient creatures whose warm blood connects them to us. Moby Dick is our most defiantly archaic great novel; it is difficult, experimental, rambling and just … strange.

Melville seems so exhilarated in his composition that he throws everything at us – the minstrel show of Fleece preaching to the sharks; Queequeg performing a caesarean on a whale head and pulling Tashtego back into life; a whole chapter devoted to the sperm whale’s penis and the marvelous “cassock” that can be made from its skin; the goofy spookiness of Fedallah and the Asian “tigers” stashed in the hold by Ahab, his personal boat crew of devils to assist his vengeance on the white whale; the on again-off again narration of Ishmael — a character who begins authentically and then mutates into the author’s unmistakable voice; Queequeg selling shrunken heads on the streets of pious Nantucket; Melville’s interspersed use of soliloquys and stage settings and dialogue in a work of prose. The novel in its complexity and dizzying movement often disorients the reader.

You should read it because it is the essential American novel; no other American novel takes such intellectual risks, and that makes it rich beyond measure.

“The Flurry”: William Duke, 1848

Moby Dick tells our oldest story – of our hubris, of our innate compulsion to deny all limits, to violate all boundaries, of our consistent belief that we know better than both nature and any God. It describes our American pursuit of a total, annihilating freedom, one that proclaims itself unrestricted by all governance except that of the individual, alone and supreme, atomized and alienated.

No American novelist had (or has) a more capacious, restless mind than Melville. Moby Dick is the story of a chase, but it is also the best psychological study we have of lucid megalomania, of a peculiar American fanaticism skilled in conversion, and of our schizoid and violent affair with wild nature. In the chapters that seek to define and explain the whale and all that Melville knew about whaling, he makes himself into an essayist akin to Montaigne, one who uses the specifics about a whale’s head, bones, habits, eye, heart, etc. and the industry’s methods to give us his expansive notions about the human condition. The whale serves as the structural hub from which spokes of speculation and seeking extend. His goal seemed to be to create an encyclopedia of whaling in all its physical particulars, a metaphysical encyclopedia that confronted fundamental mysteries about evil, free will, and the nature of God, and a story Biblical and Shakespearean in its structures, subject, tone and character development. This is the great American philosophical novel, its only world rival being Tolstoy’s War and Peace. This is a beautiful, difficult book, filled with sentences that linger in the mind, with the inestimable portrait of Ahab, with unrivaled scenes of natural beauty and violence.

In a November, 1851 letter to Nathanial Hawthorne (to whom the book is dedicated), Melville declared that he “had written a wicked book.” He has, if wickedness means to  investigate Ahab’s assertion that we live in a universe ruled by nothing except chance, profane will and violence. The novel traces the arc of Ahab’s tragedy, but one can argue that even more so it describes a deeper, broader human tragedy, one that finds us at war with nature and with our more bloodthirsty selves. This book presages the great 20th century theme of human beings plagued by a universal anxiety, one that continually suggests that “the appalling ocean surrounds the verdant land [and] so in the soul of man there lies one insular Tahiti, full of peace and joy, but encompassed by all the horrors of the half known life (399, LVI).” *

investigate Ahab’s assertion that we live in a universe ruled by nothing except chance, profane will and violence. The novel traces the arc of Ahab’s tragedy, but one can argue that even more so it describes a deeper, broader human tragedy, one that finds us at war with nature and with our more bloodthirsty selves. This book presages the great 20th century theme of human beings plagued by a universal anxiety, one that continually suggests that “the appalling ocean surrounds the verdant land [and] so in the soul of man there lies one insular Tahiti, full of peace and joy, but encompassed by all the horrors of the half known life (399, LVI).” *

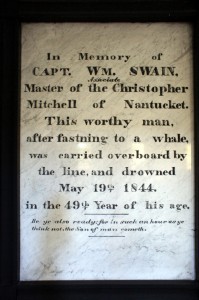

A Cenotaph from the New Bedford Whaling Chapel

Moby Dick is a wilderness novel and thus another story of men hunting outsized, powerful beasts in savage territories far from home. The whale of 1851 had been unseen by most — there were no photographs, no video images, nothing realistic for a landsman to hold in his head, but only artist’s renderings which by their very medium lean towards the mythic. Men hunted it far from land with fearsome weapons. They brought back bone and oil. It killed some of those men. The Sperm Whale took on its outsized life again in stories told by mariners. There is nothing in our time remotely like this experience.

In three more essays (posts) I hope to persuade you that the book is an astonishment, and that if you have not read it, you should, and if you have tried to read it and failed to do so, that you should try again. Winter is coming, the quietest and most intimate season and the perfect season for this book of great solitudes. Turn on the light, turn off everything else and take it up.

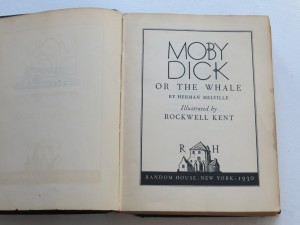

* Moby Dick Or The Whale by Herman Melville: Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. Random House: New York, 1930.

http://www.powermobydick.com/ : A very good annotated text of the entire novel

I do have a sense of humor about this love affair. Therefore, let me share this: http://vimeo.com/20367115. I get a kick out of its terrific loopiness. And I could not let you go without showing you this boy’s dream of a Japanese monster movie:  King Kong Vs. Moby Dick

King Kong Vs. Moby Dick

Providentially, I was in a Goodwill store a year ago and the Rockwell Kent fell into my lap. Since then I have tracked down the unabridged CD set (“Have ye seen the Frank Muller?”) While thus marveling at Melville, I have begun outlining a novel about the youth of The Whale. Can I count on you to scan the manuscript?