All my adult life I’ve been trying to learn how to see.

One experience came as close to a type of consecration as I’m likely to ever feel — when I was 23, I took a summer graduate course at Montana State University, Literature and the Wilderness, that asked of its students that they read 8 books and write voluminously about what they had learned. We also were taught technical climbing skills, and we spent days in the mountains of the Beartooth Wilderness. One of our assigned readings drove those changes to my life deeper into me than might otherwise have been true.

One experience came as close to a type of consecration as I’m likely to ever feel — when I was 23, I took a summer graduate course at Montana State University, Literature and the Wilderness, that asked of its students that they read 8 books and write voluminously about what they had learned. We also were taught technical climbing skills, and we spent days in the mountains of the Beartooth Wilderness. One of our assigned readings drove those changes to my life deeper into me than might otherwise have been true.

In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek Annie Dillard devotes a chapter to the process of seeing. She means learning how to be “knowledgeable” about what fills our eyes and therefore becoming equipped to look at more than the surface of something — anything, really. She taught me how to be still and wait in the woods. She showed me how to see praying mantis cases; she taught me how to let go and be an “unscrupulous observer” of the natural world; in other words, to open the aperture to full and let everything riding on the light come in.

In Pilgrim at Tinker Creek Annie Dillard devotes a chapter to the process of seeing. She means learning how to be “knowledgeable” about what fills our eyes and therefore becoming equipped to look at more than the surface of something — anything, really. She taught me how to be still and wait in the woods. She showed me how to see praying mantis cases; she taught me how to let go and be an “unscrupulous observer” of the natural world; in other words, to open the aperture to full and let everything riding on the light come in.

Since Montana, since Pilgrim, I’ve been trying to see more clearly and deeply into woods, Moby Dick, birds, teaching, poetry, landscapes, Hamlet, students of every size and range and age, novels, family, King Lear, dogs, astronomy, friends, geology, faith, movies, the Plains, the West, mountains, wolves, history … and paintings (and I hope there’s time to make this paltry list longer).

Of all the painters whose work spurred a deep resonance in me – Caravaggio, Monet, Glackens, Hopper and others, it is Andrew Wyeth to whom I keep returning. I was introduced to his paintings by someone who loved them and who collected his books and prints. It was an immersive lesson.

Of all the painters whose work spurred a deep resonance in me – Caravaggio, Monet, Glackens, Hopper and others, it is Andrew Wyeth to whom I keep returning. I was introduced to his paintings by someone who loved them and who collected his books and prints. It was an immersive lesson.

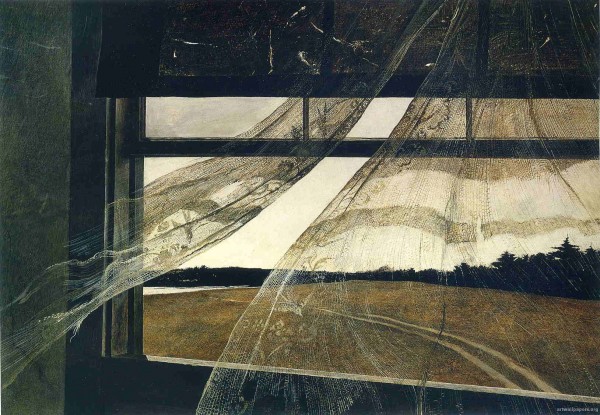

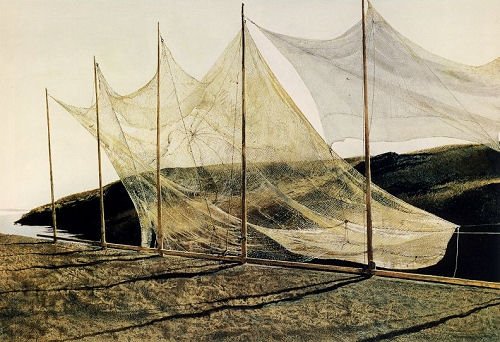

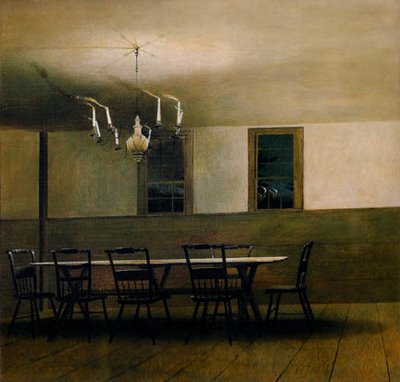

His Pennsylvania and Maine landscapes offer up a terrain that I know well, but it is not the comfort of the familiar that continues to draw me in. His eye for country is neither comforting nor sentimental; it is wide, wintry, mysterious, sentient, ancient. I know of no other painter who can make geographies and objects seem as if they possess a consciousness – logs, chains, coats, nets, wood on the side of a house, plates, beds, feathers, bells and windows, everywhere windows. The sentience comes from their possession of a story. Wyeth reminds us that every solid thing we see around us is both a ‘thing in itself’ possessing heft and gravity, and a mere translucent scrim through which we can sense the stories it contains. Look at the strength of the chairs and the glowing white plane of the table in The Witching Hour (3) or the luminous fishing nets and the fulsome wind in Pentecost (2) and then again, the evanescent curtains and the breeze made as real as your skin in Wind from the Sea (1). These scenes and objects are not illustrations attached to another story, they are something much rarer – they are indications of the soulfulness of the world, hints, because that is all even the best painter can capture, of an underlying pulse, a respiration, an awareness of something buzzing just on the other side of the solidity of the masks of all objects and places. The closer we look, the more is revealed. Their stories are in-dwelling; they wait on us to develop the prescience of sight necessary to show their deeper  natures as multifarious, perhaps even infinite. Do not the storm-coats in Squall (4), hung between the sea and the horizon, call forth pictures from you that you had not anticipated? Are not your pictures laden with portent, edged with meanings that grow clearer the longer you consider them? So that when I look at the ornate glaze of the costume-coat in Curtain Call (5), I sense the hovering presence of theaters and of great cities and other years right next to me, of cheerful crowds in narrow torch-lit streets.

natures as multifarious, perhaps even infinite. Do not the storm-coats in Squall (4), hung between the sea and the horizon, call forth pictures from you that you had not anticipated? Are not your pictures laden with portent, edged with meanings that grow clearer the longer you consider them? So that when I look at the ornate glaze of the costume-coat in Curtain Call (5), I sense the hovering presence of theaters and of great cities and other years right next to me, of cheerful crowds in narrow torch-lit streets.

As near as I can tell great painters paint both themselves and the world as they imagine both and as they physically see both. They find ways to see that let in the light. They find the patience to wait on the light, and then through trial and error they discover their talent in shaping the images as revealed by the light. One facet of Wyeth’s genius lies in his ability to assure us that the hard, old world contains fresh worlds beneath the hard, old surfaces.

It is our responsibility to be awake enough to let the light they shaped shape our seeing.

Mike, Love this post! Takes me a long way back!

DKB