Most of you who read this lead comfortable lives. You have never been hunted through an unforgiving wilderness by others who mean to kill you. Almost certainly, you have never had to face another in a struggle which will end in your death or his. I doubt that, through no choice of your own, you have ever been grievously hungry. Then as a senior in high school or a college freshman or just as a person with limited time to read something, why read King Lear, and any tragedy for that matter, where we swing into ferocious contact with horrors, and where we watch characters we care about being hurt and defeated? Why travel to see the play performed?

Most of you who read this lead comfortable lives. You have never been hunted through an unforgiving wilderness by others who mean to kill you. Almost certainly, you have never had to face another in a struggle which will end in your death or his. I doubt that, through no choice of your own, you have ever been grievously hungry. Then as a senior in high school or a college freshman or just as a person with limited time to read something, why read King Lear, and any tragedy for that matter, where we swing into ferocious contact with horrors, and where we watch characters we care about being hurt and defeated? Why travel to see the play performed?

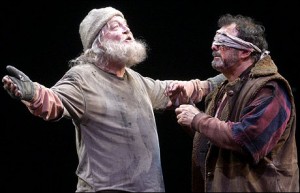

Ian McKellen as Lear

First, we want to witness something thrilling happen in the same room, in real time. I saw Ralph Fiennes perform Hamlet on Broadway years ago. He was such a fiery, immediate presence that I felt as if he were living a part of a real man’s life right_there in front of hundreds of us.

Another reason — we do like to safely watch others in extreme situations, especially if they are cartoon figures or imagined characters. We should never underestimate our appetite for the vicarious enjoyment of fictional conflict. We want the dramatic. We love delicious stories of intimate fighting. In King Lear, even though we know what happens, we want to see how it happens this time, on this night.

In the presence of staged chaos maybe we also like being reminded of our own well-being, of our safe havens and lawfully secure communities.

King Lear has been in performance for 406 years this Christmas; we keep attending a play where, a few yards away from us on stage, we watch old men tortured, blood spilled,  madness blossom. We pay to do this. Why?

madness blossom. We pay to do this. Why?

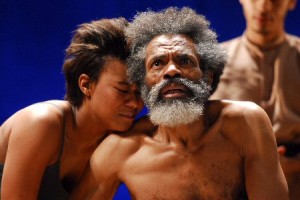

James Earl Jones as Lear

We watch the action of the stage as part of a communal ceremony; we are one member of an audience, but we may not speak during the performance. Thus we are also one person taking it all in and thinking and connecting as a solitary intelligence.

That solitary intelligence wants to be challenged. This play asks us to confront all those secret anxieties we do not speak of among friends over dinner – how might I act if threatened? Can I really trust my family members not to betray me? If deprived of shelter, warmth and food, what would I do? Could I hold on? Do my friends love me enough to risk themselves for me? Would I step into danger for them? What is my worst fear? Could I endure its reality? Under pressure will I be honorable? Am I a coward?

And if you have time only to read it? Such reading demands quiet and solitude. The noise of our other life is set aside for a while. Then characters rise up inside our imaginations. In the separateness of our reading, our self meets theirs. Something paradoxical occurs. We both escape into their realm and match ourselves against it. Both give light, and both give our days a richer texture.

Read lines and speeches aloud. Catch the rhythm of the language, and you will begin to catch the reality of the character. Your understanding of the language will improve. The play will open up to you even more.

King Lear is meant to be disturbing, funny, thought provoking, alive, truthful. Aren’t you sick of the falseness of advertising, of politicians, of an empty media culture filled with shouting and monstrous displays of conceit? Shakespeare tried to tell the truth, and if we are in the right place, great actors and actresses might bring the whole experience to us in images so stark with power that we will never forget them.

In Posts 130 and 129 I have both led you through an entire Act and focused on close readings of two soliloquies. For Acts IV and V I want to focus on Lear in actions I have found most memorable. Once again, you, with the assistance of your teacher, must enter the play. Use your intelligence, intuition and life experience to give it meaning. Ultimately, that meaning must be personal. We only care about books that we connect to in ways beyond the purely academic. For example, what stories that you have lived or been told connect you to King Lear?

One story: On a visit to a wintry New York in the 70’s my friend and I were walking past Bloomingdale’s, happy to be in excited crowds. Passing the main entrance of the store we saw a large black man standing on a thick piece of cardboard. A big dog lay between his feet, head on its paws, eyes closed. The man wore sunglasses, a knit cap, a long heavy coat, and solid, thick-soled boots. He was playing the harmonica — straight backed, head upright, water vapor coming off him like a cloud. His face was clean shaven, his neck laced with muscle.

We slid next to a wall and watched him; he did not speak to the crowds. He only played one bluesy melody after another. He was very good. The basket next to the dog was heavy with change and bills. He kept to the dignity of silence. No beggar, he was earning his living. The crowds surged around him as if he were a rock in a stream.

I see his face and his bearing on that cold day when I think of the kind of man Lear would have been before old age took its toll.

In Acts IV and V you will witness an invasion meant to rescue and restore order, the aftermath of a battle, jealousies burning so hot they become murderous, reconciliations, a disappearance, sword fights, killings, a nation regained at a terrible cost, and a shocking entrance that suggests that the laws we believe should govern all moral lives have been broken.

These moments from the final Acts remain with me more than most:

In Act IV, scene vi, Lear “fantastically dressed with wild flowers” encounters a wounded Gloucester and a still disguised Edgar in “fields near Dover.” Lear, antic and energetic holds them in thrall. His conversation with Gloucester ranges over the subjects of mice, the common deceit practiced upon a king by sycophants, the damages produced by lust, the nature of babies, and the practice of power.

That last matter of power shows a man removed from authority who now understands how authority might tap into the human capacity for corruption and bring it to the surface:

See how yond justice rails upon yond simple thief … change places; and handy dandy which is the justice, which the thief (154-156)?

This ragged man who once held sway over a great nation now believes this about rulers:

Thou hast seen a farmer’s dog bark at a beggar? And the creature run from the cur? There thou mighst behold the great image of authority; a dog’s obeyed in office (158-163).

He understands that individual corruption, inescapable in all of us, might produce a rancid hypocrisy when we are granted the right to punish another:

Thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody hand! Why dost thou lash that whore? Strip thy own back: thou hotly lusts to use her in that kind for which thou whipp’st her (164-167).

In another example:

The usurer hangs the cozener (167-168).

He can now articulate the truth about the bond that links wealth to injustice:

Through tatter’d clothes great vices do appear; robes and furr’d gowns hide all. Plate sin with gold, and the strong lance of justice hurtles breaks; arm it in rags, a pigmy’s straw does pierce it (169-172).

He sees the playacting at wisdom that rotten politicians practice:

… a scurvy politician seem(s) to see the things thou dost not (175-176).

Only now, upon being reduced in status to a mad man wandering the road, bereft of his kingdom, and stripped of all authority, can he see that the mechanisms of power can be warped by arrogance and lies.

Later in Act IV, having been rescued by Cordelia’s men, he meets her for the first time since he cursed her in the first scene of the play. He would choose to die to make up for the misery he caused her:

misery he caused her:

Lear: Be your tears wet? Yes, in faith. I pray, weep not. If you have poison for me, I will drink it. I know you do not love me; for your sisters have, as I do remember, done me wrong. You have some cause, they have not. Cordelia: No cause, no cause (IV, vii, 71-76).”

Before everything cracked apart, Lear had thought to have spent his last years with her. Now, his willingness to accept sacrificial death at her hands, and Cordelia’s tearful answer, restores their love.

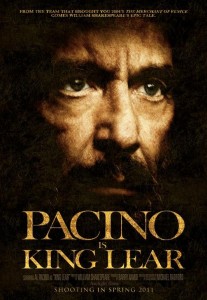

Christopher Plummer as Lear

Lear and Cordelia are soon captured by Edmund and his forces. Cordelia struggles to remain composed. She understands that Edmund means to kill them. I think Laurence Olivier’s line readings of this speech are just right — lucid, aware of the danger, he embraces her:

Come, let’s away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage.

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live

And pray and sing and tell old tales and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too —

Who loses and who wins, who’s in, who’s out —

And take upon’s the mystery of things

As if we were God’s spies. And we’ll wear out

In a walled prison packs and sects of great ones

That ebb and flow by the moon (V, iii, 8-19).

In this speech I think we see the persona of the man who had been the King before his abdication, the man who had provoked such depths of loyalty and love in Cordelia, Kent and the Fool. He spins out a scenario he cannot believe in, one filled with tenderness and laughter. Both the slyness of Olivier’s expressions and the sweet tones of his voice show that he hopes to create a boundary of protection for Cordelia, even if all he has as a weapon are his words and presence.

In this speech I think we see the persona of the man who had been the King before his abdication, the man who had provoked such depths of loyalty and love in Cordelia, Kent and the Fool. He spins out a scenario he cannot believe in, one filled with tenderness and laughter. Both the slyness of Olivier’s expressions and the sweet tones of his voice show that he hopes to create a boundary of protection for Cordelia, even if all he has as a weapon are his words and presence.

I will not take you through the last 300 lines of this play. You must confront those on your own or with your teacher. You must set aside lines and images that resonate for you. You must work towards your own meanings. My summation would ruin their effect upon you. They have the potential to change your life. Truly.

This is my final word on King Lear and other books that I read again and again: I am a believer in books as agents of alchemy — the magic comes not in gold but in their endless domains filled with other mortal spirits like us. Our transformation might come in the wisdom we find there to apply to our own attempts to make a good life.

Pacino as King Lear may be slated for release in 2013.