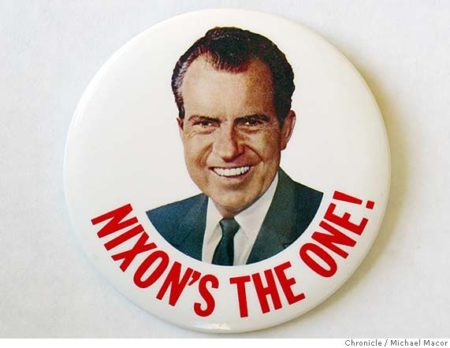

When Nixon was running in ‘68 and then elected, I watched him with fascination, a stingy respect and a deep wariness. This was a very smart guy, very tough, resourceful, resilient, and a true rags to power story. No one had handed him a thing — he was not raised in wealth, he worked hard at everything, he received no million dollar loans, he did not evade service during WWII and he gave off a kind of clunky awkwardness with others that reminded me of my own gawky floundering. He was also the same politician who cultivated Wallace’s supporters and brought them fully into the GOP. He gave orders that killed hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese even when he knew the War could not be won. Thirty thousand more American soldiers died during his first term in office. Ultimately, in service to his desire to win at all costs, he lied again and again and again about Watergate.

When Nixon was running in ‘68 and then elected, I watched him with fascination, a stingy respect and a deep wariness. This was a very smart guy, very tough, resourceful, resilient, and a true rags to power story. No one had handed him a thing — he was not raised in wealth, he worked hard at everything, he received no million dollar loans, he did not evade service during WWII and he gave off a kind of clunky awkwardness with others that reminded me of my own gawky floundering. He was also the same politician who cultivated Wallace’s supporters and brought them fully into the GOP. He gave orders that killed hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese even when he knew the War could not be won. Thirty thousand more American soldiers died during his first term in office. Ultimately, in service to his desire to win at all costs, he lied again and again and again about Watergate.

In retrospect, he seems that most contradictory of modern Presidents, someone who at points in his career evinced virtues we want in a leader — thoughtfulness, a subtle understanding of historical and political complexity, an initial decency as a human being in his youth, but who lost everything to his ambition and the ruthlessness that he believed had to accompany it.

In looking back, I see a chance that he might have altered all this history to come. Perhaps, in late October of 1960, if he had made that phone call to the Georgia governor about securing Martin Luther King’s safety in a rural country jail, he might have taken enough of the black vote to beat Kennedy — the assassination in Dallas never happens and the Republican Party does not become the party of voter suppression and white resentment. His gifts supersede his flaws and the great nationwide unraveling we are now witnessing is avoided.

Or must we go back to Goldwater who might have changed racial dynamics for the better if he had understood and embraced the civil rights movement instead of rejecting Brown vs Board of Education and voting against the 1964 Civil Rights Bill.

Or perhaps all such possibilities are futile. Perhaps we will always have “corners of the country [that] put their hands in their pockets, whistle and quietly shuffle off, as if [such] history was never theirs.”*

Instead, Nixon (and his amanuensis, Kissinger) lie about Laos and Cambodia. Nixon creates enemies lists. He tries to subvert the FBI and the Justice Department to serve his needs and not the rule of law. In the Watergate episode, he covers up a subversion of the ‘72 election and fails and goes down. Perhaps it is here that the cynicism about politics that has always coursed through the American bloodstream becomes supercharged.

In the pendulum swing of the reaction to Nixon and Ford’s pardon, Carter, an evangelical Baptist, defeats Ford and inherits an economy that is being eaten from within by the effects of inflation and recession. He is never able to recover. Iran came due and erupted in revolution. The US had been covertly active there since WWII, helping to overthrow a democratically elected Prime Minister and install a king who employed thugs trained to torture in the US. The Iranians took our diplomats as hostages, their hostility to the US a factor in Middle East geopolitics down to this day. At the end of every newscast, Walter Cronkite signed off by telling his viewers how many days the American hostages had been held captive. Ellen Goodman noted that “this sentence [had] become the most powerful subliminal editorial in America.” She described “the feelings of the country [running] red.” I remember a time of belligerence, industrial rot, deep uncertainty about daily life, about jobs, a continuous low level hum of fear — all of this producing a kind of abiding anger combined with nostalgia for an impervious American power. In response, Reagan finds his moment. Former governor of California, a strong contender for the Republican nomination in ’76, he was an actor who knew how to keep to his script, work the camera and deliver both charm and a line.

Maybe we have always been a hurtling mess, barely hanging together as a nation, barely rescued in moments of extraordinary crisis by extraordinary leaders — Washington, Lincoln, FDR. Maybe we have always lived in the present, ignorant of history, unconcerned by cause and effect, dismissive of warnings. After all, we are Americans, the exceptional people, the chosen nation, collectively good and innocent, always avoiding the terrible stumble off the cliff … except when we are not, except when we do not.

*“In Trump’s Remarks, Black Churches See a Nation Backsliding”. The New York Times, January 15, 2018