It will take a generation of able historians to decipher the patterns and describe how all of this went so wrong, how in 2018 Americans found themselves so disoriented, alienated, furious, and feeling as if they have been seized by forces over which they have no control. It did not begin with Trump. I cannot tell where it began but only describe the events I have lived through that seem pieces of a larger, still inscrutable American and global narrative.

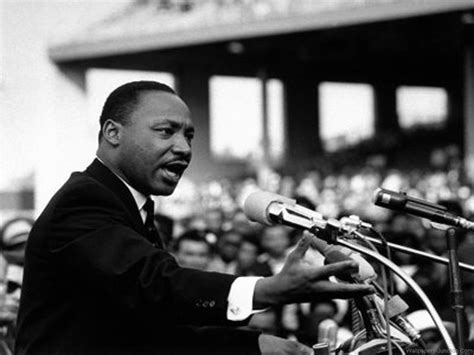

A white boy brought up in white towns and schools in what felt like a white land, I remember watching black children and men in white shirts and women in Sunday dresses being blown against storefronts by high pressure water hoses, attacked by snarling police officers wielding snarling German Shepherds. What is going on? These are the first images of a American political and social dynamic that came into me — only gradually did I begin to understand the history and the enduring hatred that governed those actions. In the midst of that tumult Martin Luther King emerges, a small man in a dark suit on a platform under a broiling sun speaking to a great multitude gathered on the Mall in DC. He was filled with a controlled fire. And then, in memories so sudden they feel like explosions, the TV screens were filled with helicopters landing in clearings next to jungles or in rice paddies and Marines were leaping out of them or being carried back to them, slung on the shoulders of other Marines. Then bomb patterns creating long lines of fire and smoke and concussive waves across trees and villages while a voice recites sentences referencing body counts and guerillas and communists.

A white boy brought up in white towns and schools in what felt like a white land, I remember watching black children and men in white shirts and women in Sunday dresses being blown against storefronts by high pressure water hoses, attacked by snarling police officers wielding snarling German Shepherds. What is going on? These are the first images of a American political and social dynamic that came into me — only gradually did I begin to understand the history and the enduring hatred that governed those actions. In the midst of that tumult Martin Luther King emerges, a small man in a dark suit on a platform under a broiling sun speaking to a great multitude gathered on the Mall in DC. He was filled with a controlled fire. And then, in memories so sudden they feel like explosions, the TV screens were filled with helicopters landing in clearings next to jungles or in rice paddies and Marines were leaping out of them or being carried back to them, slung on the shoulders of other Marines. Then bomb patterns creating long lines of fire and smoke and concussive waves across trees and villages while a voice recites sentences referencing body counts and guerillas and communists.

For me, these two sets of pictures joined and made a framework my adolescent self tried to put together. Now, in 2018, that framework looks skeletal, like the ruin of building battered by murder, by cruelty and stupidity and lies, by neglect and narcissism, by the implacable destructive force of 21st century capitol, and by the whirr of gadgets and noise we cannot escape.

In March of 1968, My Lai takes place and is covered-up until the story breaks over 1 year later. Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat, defeated by Vietnam’s insoluble problems and by the blindness and lies of his Administration, announces he will not run for reelection. The inflationary pressures that would ravage the country in the 70’s begin to exert their influence. In April, King is murdered, in June, Robert Kennedy. In city after city, black rage combusts. In August, the Republicans nominate Nixon in Miami at a well-organized Convention.* In August, the Democrats tear themselves apart in Chicago. Clumps of police and protesters fight each other outside; on the floor of the Convention, a kind of 3 day surging chaos. Nixon wins by a hair in November. George Wallace takes five southern states and over 9 million votes and the Republican Party from that moment forward to the present day aligns itself with those revanchist forces.

In March of 1968, My Lai takes place and is covered-up until the story breaks over 1 year later. Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat, defeated by Vietnam’s insoluble problems and by the blindness and lies of his Administration, announces he will not run for reelection. The inflationary pressures that would ravage the country in the 70’s begin to exert their influence. In April, King is murdered, in June, Robert Kennedy. In city after city, black rage combusts. In August, the Republicans nominate Nixon in Miami at a well-organized Convention.* In August, the Democrats tear themselves apart in Chicago. Clumps of police and protesters fight each other outside; on the floor of the Convention, a kind of 3 day surging chaos. Nixon wins by a hair in November. George Wallace takes five southern states and over 9 million votes and the Republican Party from that moment forward to the present day aligns itself with those revanchist forces.

When I think of Lyndon Johnson now, I think in Shakespearean terms, of a good man man caught within what he believed to be the zero-sum demands of the Cold War, that every US recalibration or withdrawal was a win for the Russians or Chinese; caught within the nebulous idea of American might, that psychological projection of machismo; caught within the will to believe in the mission when the facts of the mission subverted its raison d’etre on a daily basis. I think he might have been a great President, perhaps the best since FDR, but Vietnam broke him.

I was 16 in ‘68, often untethered from everything except my own narrow concerns, my sense of adolescent time so simultaneously slow and fast, but the roar of that year’s detonations broke through. Still, I never remember thinking that we were coming apart, that nothing could repair the damage. Perhaps at 16 I could not imagine such calamities becoming the norm or perhaps because we lived apart from everlasting noise, apart from a 24 hour news cycle of thought-devouring media, everlasting connectivity, faux outrage shouting at us all day, all night, real outrages vanishing from our attention after a day.

In Ken Burns’ series on Vietnam a former Marine speculates that the whole experience of that war “drove a stake through the heart of America, and we have never recovered.” All these years later, that seems about right. Perhaps it, together with all the other awful events of ‘68, injected into our body-politic a paralyzing fear of disorder, an instinctive distrust of government, and in Wallace, that first willingness of tens of millions to give consideration to a fanatic and demagogue as a potential champion.

*Since then, it has emerged that Nixon may very well have conspired to hinder peace talks between the United States and North Vietnam.