Hamlet is intoxicating. It may be the most disorienting of Shakespeare’s great plays for the Son is the most accomplished shapeshifter of all his great characters. He is so powerful that for one actor he came into real life outside of the lines: “Daniel Day Lewis withdrew from the part in mid-run in 1989 after he [said that he had begun to see] his recently deceased father on stage at the National Theater (5).”*

Hamlet is intimate. Who else shows so much of his inner life, his whirling mind, his devastation. Horatio is not his best friend. We are, the readers and watchers, just as we are his judges. He is so screwed up — circumstances demolish him. His father, a warrior King dies mysteriously while Hamlet is far from home. Hamlet, a scholar, not a warrior, returns to find his mother in love with his Uncle, a man who makes his entrance in full command of the Kingship, and before celebrating his wedding, gives patronizing, creepy advice to his nephew: “Think of me as a father.” Then his father’s ghost gives him a command to revenge his murder, but oh, Hamlet must not soil his conscience by doing so, and oh yes, he must leave his mother out of it. How would our lives be shredded if a dead father, mother, wife, child or lover returned to us while we were alone and in darkness, and there told us that we were “bound” to do his or her bidding?

Hamlet is intimate. Who else shows so much of his inner life, his whirling mind, his devastation. Horatio is not his best friend. We are, the readers and watchers, just as we are his judges. He is so screwed up — circumstances demolish him. His father, a warrior King dies mysteriously while Hamlet is far from home. Hamlet, a scholar, not a warrior, returns to find his mother in love with his Uncle, a man who makes his entrance in full command of the Kingship, and before celebrating his wedding, gives patronizing, creepy advice to his nephew: “Think of me as a father.” Then his father’s ghost gives him a command to revenge his murder, but oh, Hamlet must not soil his conscience by doing so, and oh yes, he must leave his mother out of it. How would our lives be shredded if a dead father, mother, wife, child or lover returned to us while we were alone and in darkness, and there told us that we were “bound” to do his or her bidding?

In Hamlet’s first scene he shows himself to possess a supremely quick mind, the most fluent ability with language of any of Shakespeare’s characters#. But he is neither measured, calm nor wise. He is exhausted. Only in the final scene of the play does his glassine, sharded mind stop its splintering.

Hamlet is not a hero. Ophelia describes him as a scholar, a courtier and a soldier. We witness his skill with a sword, but he has never fought in combat. His first inclination is never for action but always for thought.

When his father commands him to revenge, Hamlet’s instinct towards obedience shows itself in a metaphor about love and meditation, not one about bloodletting or fire.

Before the Ghost appears to Hamlet, Claudius humiliates him for mourning his father for too long. Claudius describes him as “obstinate”, “impatient”, “unmanly”, “simple’, “peevish’ and “vulgar”. Claudius does this in front of his mother, Ophelia, Laertes, diplomats, the assembled Court, Polonius — all those whose support he would need should he ever become King. Had Claudius tried this with the old King, he would have had Claudius’ heart on a stick. Hamlet says nothing.

Hamlet is not Othello, a warrior so charismatic, successful and courageous that he has earned the trust and respect of the Venetian state in spite of their prejudices about his race.

He is not Macbeth, a Lord in Scotland and a man who wins two battles in one day and is beloved of his King.

He is not Lear, so successful that His England is the most powerful country in Europe.

He is not his father, a King who killed another King when land and honor were at stake.

He is not Fortinbras, a man he envies, a ruthless son who single-mindedly seeks to avenge his father.

Hamlet has done nothing in his life worth noting. He is 30, a reader, a lover of plays, good with words, bright, handsome, great fun when he is right in his mind and heart as implied by his friendship with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. There is the sense of someone who has never really had to do anything hard, a feeling of indulgence about him. We wonder sometimes why he just does not shut up and get on with it.

That ‘wondering’ is full of hubris. Hamlet is trapped as we would be trapped. He has no way out of his dilemma.

Kill Claudius? The nature of his character argues against premeditated killing. He has spent his life with books, not battleaxes and wounds. He has to be enraged to kill. He has to become an unthinking, sudden weapon.

Leave the Kingdom? He is the son of the rightful King, to the manor born and raised, and his father has traveled back from the dead to ask him to revenge him. How could he live with himself if he abandoned his country so as to evade this twin calling? If it were you standing upon the ship’s deck as it cast off for safety in another land, would you not think yourself an irredeemable coward?

Lead a revolt and overthrow the King as Laertes might have done? Laertes has a certifiable reason — his father dies suddenly and mysteriously, his body is buried without ceremony and secretly, and the people who rally to Laertes’ side apparently believe “the pestilent speeches of his father’s death.” Hamlet could tell the crowd that his father’s ghost appeared to him and told him that he had been murdered and King Claudius was the killer. Who would believe him? No one else heard the Ghost’s story. Hamlet has been wandering around the castle acting out of sorts. He has humiliated his mother, Ophelia and the King at a public gathering , and he has killed an old man who was hiding behind a curtain.

Or perhaps Hamlet could do nothing at all. He speaks of his desire to die — one so young loves death so much that only a fear of the afterlife keeps him from taking that step. How could he make the decision to remain in Claudius’ shadow, spied upon, patronized, exposed to the affection between Claudius and his mother for years to come? This psychic endurance from a man who, before he knew his uncle was the murderer of his father, said that “all the uses of this world are stale and flat,” and that the world itself is “rank and gross”? He could not bear it. The pain would be too great.

Again and again Hamlet claws his way back to a kind of stability only to be knocked down — by his Mother’s marriage and Claudius’ kingship and his public humiliation, then the Ghost, then the ugliness of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s lies, then Ophelia’s role as bait.

He is a man beset, unable to find a place to rest. “Foul deeds” do rise. He is pursued by them — by the knowledge given him by the Ghost … and then the knowledge that Claudius wants him dead … and then in the final scene the lettered proof he carries in his pocket of Claudius’ guilt … and then Laertes’ desire to avenge his father’s murder and his sister’s suicide … and then his mother’s murder. Seamus Heaney caught the sense of fracture and constriction in him:

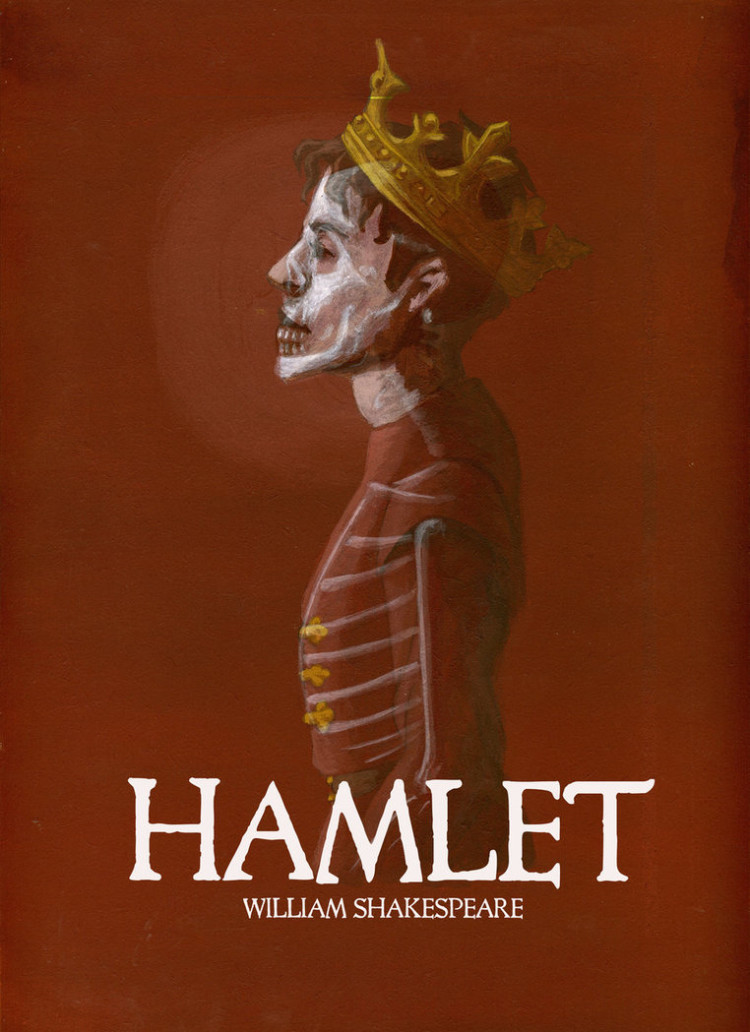

I am Hamlet the Dane,/ skull-handler, parablist,/ smeller of rot

in the state, infused/ with its poisons,/ pinioned by ghosts/ and affections

murders and pieties,/ coming to consciousness/ by jumping in graves,/ dithering, blathering.**

Hamlet feels very close to a Greek Tragedy in its inexorable tightening of the bonds of fate around its namesake. In his entrapment we are most like the Prince. We too, especially as we age, find ourselves blocked by our history, by our past choices, by our lack of nerve. We too have been “pinioned’ by money problems or loneliness and alienation. We too dither and blather, and only gradually find ourselves “coming to consciousness” and discovering, too often too late, a clarity of vision and a chance for peace.

#perhaps with the exception of Falstaff

*from The Arden Hamlet

**from the poem “Viking Dublin: Trial Pieces” by Seamus Heaney