Outside of Chartres we drove past miles of bright yellow fields of mustard in a flat, green landscape devoid of strip malls. Only walled farms and their outbuildings broke up the roll of the countryside. Throughout our 800 mile loop this was to be the pattern: city or town, village, countryside — we saw no suburban sprawl. Wherever else the French may be struggling, they seem to have done this right. In the Departments of Eure-et-Loir, Orne, Calvados and Eure, the landscape appears divided into communities and open spaces, one serving to compliment and make more inviting the other.

Outside of Chartres we drove past miles of bright yellow fields of mustard in a flat, green landscape devoid of strip malls. Only walled farms and their outbuildings broke up the roll of the countryside. Throughout our 800 mile loop this was to be the pattern: city or town, village, countryside — we saw no suburban sprawl. Wherever else the French may be struggling, they seem to have done this right. In the Departments of Eure-et-Loir, Orne, Calvados and Eure, the landscape appears divided into communities and open spaces, one serving to compliment and make more inviting the other.

In the old Norman town of Dinan, the Rue du Jerzual bends its way steeply down from the old ramparts to the river Rance. A lane more than a street, it is enclosed by very old stone and wood-plaster homes and shops, mingled together, and high walls. Ivy and trees overhang the walls and birdsong adds to its sense of intimacy. I heard someone practicing scales on a cello, the music coming out of opened windows above me.

In the old Norman town of Dinan, the Rue du Jerzual bends its way steeply down from the old ramparts to the river Rance. A lane more than a street, it is enclosed by very old stone and wood-plaster homes and shops, mingled together, and high walls. Ivy and trees overhang the walls and birdsong adds to its sense of intimacy. I heard someone practicing scales on a cello, the music coming out of opened windows above me.

The French love gates and privacy. Standing on my toes outside one home where bright red roses tumbled over the edge of a wall, I could see wires crossed and angled above a small courtyard; attached every few inches were small fixtures like Christmas tree lights. I thought how lucky one would be to pass through that gate at the end of a day; I sensed that that little courtyard would be a place of ease away from observation.

Small, decorative touches constantly drew my eye — color on windowsills, fixtures, rain pipes, carved figures, signs. In such confined spaces, the decorative touches give signals of individual taste and enliven the eyes of passers-by. They make the street humane rather than just a thoroughfare. To live here would make one aware of your neighbors’ gestures of style, of the subtle power of small vistas, how the textures of stone alter a sense of place , and of the way that gardens can widen a restricted space.

Small, decorative touches constantly drew my eye — color on windowsills, fixtures, rain pipes, carved figures, signs. In such confined spaces, the decorative touches give signals of individual taste and enliven the eyes of passers-by. They make the street humane rather than just a thoroughfare. To live here would make one aware of your neighbors’ gestures of style, of the subtle power of small vistas, how the textures of stone alter a sense of place , and of the way that gardens can widen a restricted space.

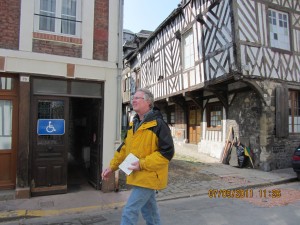

The narrowness of so many streets in the older towns invites an inadvertent eavesdropping, an uninvited invitation to share. For example, in Chartres I stopped suddenly to listen to a sweet voice sing the first verse of the La Marseillaise from a window above another hidden courtyard. Along one 14 foot wide and ½ mile long street in Honfleur, La Rue Haute, shops and homes were interspersed for the first 250 yards. If you lived here, you could step out of your front door and walk a few feet to buy clothes, wine, antiques, dine at a restaurant, visit an art gallery. Past that shared space, homes took over, each between 2 and 3 stories in height and 14 to 15 feet wide, constructed of brick, stone or wood and plaster. Many of the windows possessed shutters and some, big wooden gates. The sun struck the upper stories where windows had been thrown open. Even in such  tight quarters as this street, I had the feeling that some balance had been struck between privacy and community.

tight quarters as this street, I had the feeling that some balance had been struck between privacy and community.  Someone living here would walk to markets, to take the night air, just to stroll. The residents must see each other and perhaps know each other by first name. Shared concerns might unite them – traffic, parking, common utilities and their efficiency. Both in town and outside, the French seem to be consciously trying to design a balance between privacy and openness, between the expansiveness of the country side and the intimate ties of neighborliness in these narrow streets.

Someone living here would walk to markets, to take the night air, just to stroll. The residents must see each other and perhaps know each other by first name. Shared concerns might unite them – traffic, parking, common utilities and their efficiency. Both in town and outside, the French seem to be consciously trying to design a balance between privacy and openness, between the expansiveness of the country side and the intimate ties of neighborliness in these narrow streets.

We saw scruffy dogs everywhere, many walking unleashed but responsive to their owners’ often quiet commands. More couples than in the States walked arm in arm or held hands. We sat outside in lots of cafes. In Honfleur, little Leon, a black and white Jack Russell jumped into and out of his master’s lap, a thin, smiling man in a black beret who happily chatted and read the newspaper while Leon greeted passers-by.

Lots of men wore scarves. I saw more older men and women with canes and many smokers, but very few who were overweight and almost none who were obese. We saw very little casual, sloppy dress. Young and old alike looked put together and stylish.

In opposition to scorched earth capitalism, the French have so far chosen to preserve huge swatches of farmland; consequently there are outdoor markets filled with fresh local food once or twice a week in every village and city. In Dinan and Chartres, Honfleur, Giverny and Paris we walked among bumping and swaying crowds, striking up conversations. Out in the air I watched good natured negotiations over price and greetings exchanged between regular customers and established vendors. On one lane of one market I could have bought clothes or sausages, fish, eyeglasses, rings and earrings, bad art, gigantic lettuces, figs and bread of every description, tiny doughnuts so succulent that I could have gorged myself and smiled the entire time, DVD’s and books, roses and toys.

In opposition to scorched earth capitalism, the French have so far chosen to preserve huge swatches of farmland; consequently there are outdoor markets filled with fresh local food once or twice a week in every village and city. In Dinan and Chartres, Honfleur, Giverny and Paris we walked among bumping and swaying crowds, striking up conversations. Out in the air I watched good natured negotiations over price and greetings exchanged between regular customers and established vendors. On one lane of one market I could have bought clothes or sausages, fish, eyeglasses, rings and earrings, bad art, gigantic lettuces, figs and bread of every description, tiny doughnuts so succulent that I could have gorged myself and smiled the entire time, DVD’s and books, roses and toys.

One virtue of wandering down streets is that the very aimlessness of such walking heightens your perceptions. Instead of going somewhere, you are going where your eye and ear and curiosity lead and therefore, serendipitously, you encourage your quality of delight; you give it room to be provoked. You have slowed down. You see more. The niches and corners of little domains give themselves to you.

One virtue of wandering down streets is that the very aimlessness of such walking heightens your perceptions. Instead of going somewhere, you are going where your eye and ear and curiosity lead and therefore, serendipitously, you encourage your quality of delight; you give it room to be provoked. You have slowed down. You see more. The niches and corners of little domains give themselves to you.

The other sustaining joy of being such a walker is that over and over with each new scene you are allowed to meditate on the eternal questions of all travelers: Could I live here? Which house would be mine? Where would I choose to eat and shop? How would I make my living? How long would it take to hold warm conversations in the language? What streets would I seek out? Where would I sit in this park? What café would I make my own? Who would become my friends? The world opens wider with each trip. Possibilities pour in like gifts received in surprise.