We stood in line for an hour outside of Giverny’s walls. We talked with strangers, eavesdropped, took in the rare sunshine with pleasure. Within five minutes of stepping through the doors and entering the garden, I remember distinctly saying aloud, I want to live here.

We stood in line for an hour outside of Giverny’s walls. We talked with strangers, eavesdropped, took in the rare sunshine with pleasure. Within five minutes of stepping through the doors and entering the garden, I remember distinctly saying aloud, I want to live here.

I felt besieged by color. Row upon row of flowers stretched out over a space filled with sun — great clusters of tulips, daffodils, flowering cherry and crabapple; pansies that looked like Japanese paintings, orange flowers that drooped with blossoms shaped like bells, blue forget-me-nots with a yellow center and blocks of raw pinks, violets, and purples, long rectangles of whites and oranges, red-oranges and shades of yellow from deep lemon to the last hint of afternoon light. The crowds did not matter. I could put them away and imagine this place bereft of them. A deep green bench sat in front of the house under two big trees. I thought oh what pleasure to sit there in summer after a day of good work, good wine in your hand, sitting with your wife or husband and chatting, together taking such delight in resting your eyes upon this small glory.

Giverny covers a little over 3 acres. We passed underneath the road from the gardens to the lily ponds and bamboo groves – the Water Gardens. The road is thick with traffic, but in Monet’s time he would have heard cow bells, horses and carts, the muffled conversation of walkers, the wind, all the natural songs of creatures.

Giverny covers a little over 3 acres. We passed underneath the road from the gardens to the lily ponds and bamboo groves – the Water Gardens. The road is thick with traffic, but in Monet’s time he would have heard cow bells, horses and carts, the muffled conversation of walkers, the wind, all the natural songs of creatures.

Monet bought Giverny in 1883 and labored to make it his home for work and pleasure. His studios were a stroll away within the walls. He was a disciplined painter, up with first light. If he was not painting, he was watching how light showed itself in all its permutations. When he painted, “He moved from one subject to another on a single outing as the light altered. Jeanniot said of Monet’s work habits: … His landscape is swiftly set down and could, if necessary, be considered complete after only one session, a session which lasts as long as the effect he is seeking lasts, an hour and often much less. He is always working on two or three canvases at once: he brings them all along and puts them on the easel as the light changes. This is his method.”

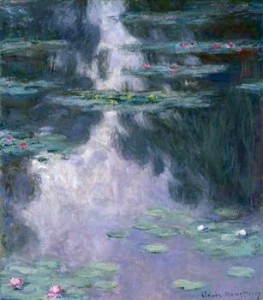

The next day in Paris we walked through the Tuilleries to the Orangerie, a museum specially constructed to display Monet’s Water Lilies paintings. In two, white, ovoid rooms 8 enormous canvases constructed of multiple panels, curved along each wall under high ceilings in perfectly calibrated lighting. We had just seen his gardens. Now we stood in front of the best work he had done there.

The next day in Paris we walked through the Tuilleries to the Orangerie, a museum specially constructed to display Monet’s Water Lilies paintings. In two, white, ovoid rooms 8 enormous canvases constructed of multiple panels, curved along each wall under high ceilings in perfectly calibrated lighting. We had just seen his gardens. Now we stood in front of the best work he had done there.

I make an effort to balance my emotions with analysis when I am trying to see something clearly, but these paintings overwhelmed me. We came to see them from Normandy, and thus my mind was replete with images of war — it was a relief to look at them. At one point I thought that these would serve to save us if God, furious and intent on annihilation, ever came calling to a contemporary Lot. He could say, “Go see Monet’s water paintings,” and preserve us all.

I set myself in front of each painting, moved back, took my glasses off and stood close, sat and gazed and moved my eyes foot by foot over their expanse. They are a sublime idea of water as an entire, peaceful world unto itself, and a concentrated perfection of an artistic vision, that rarest of events. There is nothing dated about these paintings; they are ‘present’, immediate, alive. At the same time they show light as an ethereal, Edenic form, and a force that hints at a transcendent power. I have never seen anything like them.

I set myself in front of each painting, moved back, took my glasses off and stood close, sat and gazed and moved my eyes foot by foot over their expanse. They are a sublime idea of water as an entire, peaceful world unto itself, and a concentrated perfection of an artistic vision, that rarest of events. There is nothing dated about these paintings; they are ‘present’, immediate, alive. At the same time they show light as an ethereal, Edenic form, and a force that hints at a transcendent power. I have never seen anything like them.

Elements of light skate over their surfaces. Lilies float both within the surface and on top. The eye sinks into reflections of clouds, pink skies, deep blue skies, yellow willows, blue-violets, olive-blues. Monet eliminated the horizon line. One does not look across the landscape. Your eye rests within it. When he was not painting, Monet would often sit in his little rowboat on the pond and watch the water change with the varying light.

Since our return home, I’ve been walking on our weedy lawn, walking triangles from tree to point to tree, imagining mountain laurel here, rhododendron there, the fence in place and garnered by clematis, native grasses and clumps of cone-flower and black-eyed Susan’s, columbine and asters. I want to live in Giverny, but since that cannot happen, I want to make our home a poor cousin to it.

Since our return home, I’ve been walking on our weedy lawn, walking triangles from tree to point to tree, imagining mountain laurel here, rhododendron there, the fence in place and garnered by clematis, native grasses and clumps of cone-flower and black-eyed Susan’s, columbine and asters. I want to live in Giverny, but since that cannot happen, I want to make our home a poor cousin to it.

Like Monet, I want a place where I can retreat away from grinders, industrial blowers, garbage trucks to my west and east and north, neighbors, noise, disruptions. I want a place that is serene, where bird song and wind and a train’s call miles away provide the aural landscape, a place where I can work inside my own head without continually being jerked back into the 21st century – a rude, dissonant, anarchic place.

I think we all want both a sanctuary and to be in the thick of crowds. We want work and peace, not leisure, but a peace within which one might create, and then at the end of the day to stroll a village shopping for bread and fruit, talking to neighbors, and later stand under the trees among paradisiacal scents and watch friends flock in, their voices at ease among all the other beauty.

One of my friends says that heaven is here, right now, around us. My head is too full of history to believe that, but Monet came close to making its kin. More than any writer or musician or painter of whom I am aware, Monet in middle age found a way to meld work with life seamlessly. I envy him.

One of my friends says that heaven is here, right now, around us. My head is too full of history to believe that, but Monet came close to making its kin. More than any writer or musician or painter of whom I am aware, Monet in middle age found a way to meld work with life seamlessly. I envy him.

http://www.the-art-world.com/articles/impressionist-methods.htm

This Is One Panel Only from one of eight massive canvases. It cannot do justice to the experience. It shows a whisper of the beauty. Go to Giverny. Go to the Orangerie.