During two days in April we visited Normandy battle sites. I don’t much like the verb visited in this context. Tens of thousands of human beings were smashed into nothing here within living memory. I think that most people who travel to Pointe du Hoc and Omaha Beach, Sainte-Mere-Eglise and The American Military Cemetery do so for reasons other than mere tourism.

During two days in April we visited Normandy battle sites. I don’t much like the verb visited in this context. Tens of thousands of human beings were smashed into nothing here within living memory. I think that most people who travel to Pointe du Hoc and Omaha Beach, Sainte-Mere-Eglise and The American Military Cemetery do so for reasons other than mere tourism.

Since 1945 France has evolved into a healthy democracy. Paris is the most beautiful city I have seen, and the French themselves have been friendly and helpful, and in fine humor have listened to us assault their language. This is a good place to live. Without war and killing this would not be a good place to live. It might still be a country enslaved, one ruled by murder. War and killing preserved this civilization and ours. Visit is not the right word, nor is pilgrimage, not for us anyway. For me this is more of an attempt to feel the past, to find slivers of light where I can think about the darkness.

In the cemetery of the small church in Houseville, a village a few miles inland from Utah Beach, a gray, concrete obelisk is engraved with these words: Morts Pour La France – Died For France. Sixteen names are carved on fading marble plaques. Twelve who died in World War I, three in World War II, one in Algeria. One woman’s name is listed – Maria Ferey, who died in La Guerre, The War, World War II. I can find no information on her. Close by this monument a white tombstone decorated with a photo of a young man – he has that antique face I associate with the 19th century: Auguste Sebire wore a big mustache and oiled his hair. On his tombstone: Pour la Memoire De Mon Cher Fils et Frère … – For the Memory of My Dear Son and Brother Who Died For France on February 6, 1917, Age of 38. We Pray For Him. His narrow plot is filled with flowers. Someone from the village still sees to his memory.

The Liberation Memorial for Houseville, one marker among thousands all over France, is part of the Voie De La Liberte, the Path of Freedom, and this is one link in an enormous, bittersweet chain — Km 8 of one village won back from Nazi occupation. The town center was renamed. It is now Place du 8 Juin, 1944.

The Liberation Memorial for Houseville, one marker among thousands all over France, is part of the Voie De La Liberte, the Path of Freedom, and this is one link in an enormous, bittersweet chain — Km 8 of one village won back from Nazi occupation. The town center was renamed. It is now Place du 8 Juin, 1944.

In Normandy we rented a gite, a cottage on a small farm owned by an expat British couple. A few miles west of Carentan, Houseville is an ordinary Norman village – close packed single homes surrounded by farmland. And like ordinary French villages everywhere on the 800 miles we covered in our visit, a church rests close to the town center, and those that survived the fighting have their ordinary cemeteries, each with their own memorials to those who morts pour la France. Our experience of the Invasion of June, 1944 did not begin with the beaches; it began with an awareness of French losses in what some historians have called the thirty-year war’, World Wars I and II.

France suffered 1.3 million combat deaths in WW I and over 4 million wounded, “of whom 1.5 million were permanently maimed”; add another 100,000 combat deaths in WW II and 70,000 civilian deaths due to Nazi reprisals and being caught in combat crossfire. Statistics often dull our compassion, but standing in the Houseville cemetery in front of graves of so many dead villagers elevates all that math into the worst kind of tragedy, the annihilation of the young and the slaughter of the innocents. * # ** ## How would Americans have been changed if, unprotected by oceans, we had in so short a time twice been invaded by ruthless armies, endured the ruin of a generation of young men, and been occupied for four years by beasts?

Many who rent in Houseville come for the history and bring their own stories. On one long wine-filled evening we heard about a favored guest, a Jewish New Yorker who had lied about his age so he could fight the Nazis. He landed in the first wave on Utah Beach. For many summers he has returned to the village for the June anniversary celebrations; they know him here. He has been lionized by them. Mike, our host, a man who had been in any number of threatening situations himself in his career as a photo-journalist, said to him once, “I would never have gotten out of the boat.” He was referring to the landing craft, raked by machine –gun fire. Harry said, “Yes, you would have – mates in front of you, mates in back, you would have.”

Mike’s wife, Tansy, told the story of her uncle, a commander of an RAF Lancaster Bomber. He survived 19 missions. The Lancaster’s flew into Germany at high altitudes and at night. On the way to the target, his men would all huddle together for warmth in the center of the plane. It was so terribly cold. The hardest order he had to give, mission after mission, was to the tail gunner, to tell him to return to his position. If they had been hit so badly by flak or enemy night fighters that they had to parachute out of the plane, the tail gunner would almost certainly die. He was isolated at the end of a tube so narrow that he couldn’t wear his parachute. He had to leave it at his exit hatch, a long way away.

We came to Pointe du Hoc first. I thought it might help to walk a limited area of land and to try to visualize a smaller action in scale before the enormity of the Beaches. You approach it through dense evergreens unfolding with yellow flowers, birds and bird song everywhere. The sun was brilliant, the sky a cloudless blue. We passed one shell crater. Then the land opened, and we saw the ocean and concrete bunkers and craters, dozens of craters, everywhere.

We came to Pointe du Hoc first. I thought it might help to walk a limited area of land and to try to visualize a smaller action in scale before the enormity of the Beaches. You approach it through dense evergreens unfolding with yellow flowers, birds and bird song everywhere. The sun was brilliant, the sky a cloudless blue. We passed one shell crater. Then the land opened, and we saw the ocean and concrete bunkers and craters, dozens of craters, everywhere.

Some of the bunkers were scattered in pieces, blown up into 20 foot long, thick shards. One gun emplacement has an enormous opening, fully 40 feet across, ready to accept the guns the Rangers believed were waiting for them at the top. The surviving bunkers have walls at least 6 feet thick and steel supports over the low doors — inside, 6 ½ foot ceilings and 8 feet of concrete above me — in front of me a wide, sweeping opening 2 feet high. The Germans inside would have seen the invasion fleet covering all of those 180 degrees, ships of all sizes and types, all of that force coming to kill them. Today not one ship, not one, is to be seen on that bright, blue green water.

Six smaller rooms make up the rest of the bunker. Steel blast doors sealed off the main observation space. Many have charred ceilings.

Six smaller rooms make up the rest of the bunker. Steel blast doors sealed off the main observation space. Many have charred ceilings.

I did not anticipate how narrow the shingled beach would be where they had landed and how exposed they were to enemy fire. It covers 40 yards, at most. There is no place to hide except at the base of the cliffs and all the Germans had to do was throw grenades down, one after another. I was not prepared for the shitty nature of the rock, no more than crumbly limestone and hardened silt, awful for climbing. Their ropes got wet and the cannon they were to use to shoot the grappling hooks did not work effectively. Only a few took hold. In ones and twos and threes, they began to free climb, under fire. There are occasional nooks in the cliff, indentations, but those would have only been temporary resting places. You can see that they had to get to the top, or they would die.

I find myself standing on the edge of the cliff and looking down. Waves of emotion are filling me up. My eyes are brimming.

I find myself standing on the edge of the cliff and looking down. Waves of emotion are filling me up. My eyes are brimming.

Only 225 Rangers were assigned to climb the cliffs and destroy the heavy guns believed to be here. The gun emplacements were empty. They found some 200 yards away that they destroyed with thermite grenades. They fought continuously for two days without being relieved. Only 90 were left alive or unwounded.

This still looks like a battlefield — no trees, craters and debris; nothing has been tidied up. Except that now I can see small groups of intense men and women craning their necks to listen to someone tell them what happened here. Two little girls are running up and down the sides of shell-holes on beaten, sandy paths. Their dogs are chasing them, and their parents are laughing and taking videos. Scattered in couples and threes and fours, others look out at the sea and small groups dip down into the bunkers.

Inside the Museum, 4 simple steel plaques: “In memory of those Rangers who so valiantly gave their lives on this site … 6-8 June, 1944.” A list of names: Sammie Adkins, Willis Caperton. Eddie Harding, William Moody, Fred Plumlee, Edward Sowa, George Wieburg ….” Names matter. Memory matters.

We entered Omaha Beach through the cut in the bluffs where American soldiers fought their way out of the killing zones. The street is lined with modest vacation homes, but you can still get a feel for the tactical importance of the landscape. The street drops to the beach. Push men up here, and you can

We entered Omaha Beach through the cut in the bluffs where American soldiers fought their way out of the killing zones. The street is lined with modest vacation homes, but you can still get a feel for the tactical importance of the landscape. The street drops to the beach. Push men up here, and you can

flank the bluffs. They had to get off the beach.

We parked at Dog Green and Charlie Sector, the farthest southern part of Omaha, the portion visualized in the first 20 minutes of Saving Private Ryan. The Hotel Du Casino sits on the rise behind the parking lot. More small vacation homes line a narrow road that runs parallel to the beach. Barefoot mothers and fathers are walking behind their running children at the edge of the water. Parachute riders skim along the thermals over the crests of the bluffs. Their parachutes are lime-green, blue, orange.

I cannot feel a thing.

We walked to the water. I did not turn around until I was standing in the light combers. Then, around and focusing against the sun; the sea-wall is at least 400 yards away. The heights run all the way north and south for 6 miles. I’m trying to see back 68 years.

We walked to the water. I did not turn around until I was standing in the light combers. Then, around and focusing against the sun; the sea-wall is at least 400 yards away. The heights run all the way north and south for 6 miles. I’m trying to see back 68 years.

In the thirty minutes preceding H-Hour, the Liberators and Fortresses of the Eighth Air Force dropped 13,000 bombs, but none fell on Omaha beach (91). **

Let’s say that I’m 19 and weigh, oh, 165 pounds, and I’m carrying eighty pounds of gear. I have not been shot as I stumbled off the landing craft. I haven’t drowned. I haven’t been blown to pieces by precisely sited artillery. I have to run to the beach, and then take the high ground. Machine-gun fire criss-crossed the beach and ‘as it hit the wet sand, it made a “sip-sip” sound like someone sucking on their teeth (95).’ **

The tide was rising when they landed so they were closer than me, but no matter, the bluffs loom over you as you close with them. We climbed a trail and ran into the remnants of a trench system. As we worked our way up through briars, we could see the remains of closed, or blown up, or overgrown bunkers. I stopped often and looked down and across the landing zone.

The prospect of crossing the stretch of beach in front of them seemed impossible. Any idea of trying to run through the shallows, carrying heavy equipment and in sodden clothes and boots, seemed like a bad dream in which limbs felt leaden and numb. Overburdened soldiers stood little chance. One had 750 rounds of machine-gun ammunition as well as his own equipment. Not surprisingly, many men afterwards estimated that their casualties would have been halved if the first wave had attacked carrying less weight (95). ** The total number of American dead during the first twenty-four hours was 1,465 (112). **

They landed at 6:30 a.m. in rough seas and lots of mist. They could not see very far. Everything was trying to kill them. One of the survivors, Stewart Brooks, said, “It was a numbing experience because you were crawling among the dead.”

By 8:00 a.m. they had begun to scale the hills at their strong points and kill the defenders.

There were burnt-out and still-burning vehicles, corpses, and discarded equipment in all directions. Bodies continued to wash up, rolling like logs in the surf, parallel with the water’s edge. One soldier said, ‘They looked like Madame Tussand’s. Like wax. None of it seemed real’ (105). **

In back of us cheap trailers lined up in rows behind a chain-link fence. A man was emptying grass cuttings into one of the draws that led up from the beach.

I’m straining now. I thought that from up here I would be able to bring it back, some of it; some small detail would forge a connection and an opening would appear, but the door has remained closed. I could not feel my way into the landscape. While facts may provide us with the reality of a scene, emotion provokes the imagination and allows us to leap into an empathetic understanding. I could not make the leap. I lacked the intimate knowledge of the landscape. My imagination is not powerful enough to overcome its normalcy.

The door opened again two days later in Sainte-Mere-Eglise, the town where the mannequin of the American paratrooper still hangs from the church steeple. Inside the church two stained glass windows helped me to go back. One shows a picture of the Virgin Mary in a blue gown holding the Christ child and on both sides paratroopers, chutes full, floating into the town. The other shows what looks to be St. Michael or another such knight, lifting his sword, prepared to strike. Underneath, “They Have Returned.”

The door opened again two days later in Sainte-Mere-Eglise, the town where the mannequin of the American paratrooper still hangs from the church steeple. Inside the church two stained glass windows helped me to go back. One shows a picture of the Virgin Mary in a blue gown holding the Christ child and on both sides paratroopers, chutes full, floating into the town. The other shows what looks to be St. Michael or another such knight, lifting his sword, prepared to strike. Underneath, “They Have Returned.”

I thought of the windows at Chartres. They have lasted through 800 hundred years. Maybe these too will last, and hundreds of years from now, others will stop where I had stopped and look up and be moved by these representations of thankfulness. The men who floated into this town on June 6 did not have to return. They were volunteers. Many died. The ones who lived fought to liberate strangers from oppression. Those are definitions of heroism I can accept.

In the Airborne Museum just off the Church Square, a complete glider rests in a bay. I placed my hand on its skin; it felt like an artist’s canvas after it had been stiffened by rabbit-skin glue. A portion of its wing had been removed. Its structural supports were made of thin slats of wood. Some were built by coffin makers. What would you have preferred: Surging toward the beach, sea-sick, listening to the whine of bullets above your head? Jumping out of a plane at 500 feet into a ferocious slip-stream, nothing below you but darkness? Sitting on a bench in one of those gliders, tight up against a buddy, the snap-line just released from the guide plane, feeling the turn and dip toward touch-down, the whistling of the wind all you can hear?

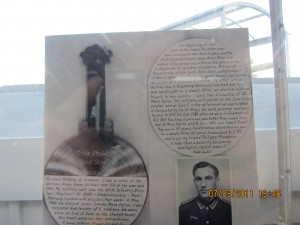

Lost in that bay, tucked into a corner, I saw a handwritten testimonial from a German soldier, once the enemy, once “the other”. Click on the photograph, and then click again. That will bring it close enough to read. The individual, flawed nature of any handwriting does not hint at the writer’s goodness or wisdom but it does assert his humanity, and anyone who hunched down in that corner and read Rudi Escher’s letter was reminded again of the contradictory nature of war – that while it devours virtue and creates horrors, it also may call forth decency. I very much like that this photo is here, in a museum that preserves the instruments and stories of war.

Lost in that bay, tucked into a corner, I saw a handwritten testimonial from a German soldier, once the enemy, once “the other”. Click on the photograph, and then click again. That will bring it close enough to read. The individual, flawed nature of any handwriting does not hint at the writer’s goodness or wisdom but it does assert his humanity, and anyone who hunched down in that corner and read Rudi Escher’s letter was reminded again of the contradictory nature of war – that while it devours virtue and creates horrors, it also may call forth decency. I very much like that this photo is here, in a museum that preserves the instruments and stories of war.

We drove north along a thin road bordered on either side for long stretches by boscage, hedgerow country, the natural feature which more than any other held up the Allied breakout from the landing zones. We saw horses and cattle, stone barns and homes; that which was here has returned. We pulled into the parking lot of the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial.  Pine trees screen the Cemetery from view. A sidewalk leads past the Visitor’s Center to an endless horizon and then the sea, and then you turn left, and you are looking down into another sector of Omaha Beach. Taps is playing on loudspeakers. You turn a corner and suddenly white marble Crosses and Stars of David appear arranged in uniform rows on perfect green grass. In my head a refrain began: Looking right to the beach and the sea, Here is where they died, and then looking left to the crosses, Here is where they rest.

Pine trees screen the Cemetery from view. A sidewalk leads past the Visitor’s Center to an endless horizon and then the sea, and then you turn left, and you are looking down into another sector of Omaha Beach. Taps is playing on loudspeakers. You turn a corner and suddenly white marble Crosses and Stars of David appear arranged in uniform rows on perfect green grass. In my head a refrain began: Looking right to the beach and the sea, Here is where they died, and then looking left to the crosses, Here is where they rest.

This was my first impression — no ornamentation, no monuments, no separation by money or class, an equality of design, a purity of effect. Each Cross or Star lists the same information. Line by line: Name/Unit/State/Day and year of death. The exception, the graves where unknown Americans are buried: Here Rest In Honored Glory/A Comrade In Arms/ Known But To God. Sea pines and squares of heather or roses are interspersed among the graves.

This was my first impression — no ornamentation, no monuments, no separation by money or class, an equality of design, a purity of effect. Each Cross or Star lists the same information. Line by line: Name/Unit/State/Day and year of death. The exception, the graves where unknown Americans are buried: Here Rest In Honored Glory/A Comrade In Arms/ Known But To God. Sea pines and squares of heather or roses are interspersed among the graves.

Fresh roses rest against the cross of Sgt. Fred Naves of California. I walk past the graves of Henry Phipps of Kentucky, Pvt. Frank Morgan and Sgt. Patsy Columbus of Pennsylvania, Heinz Grunig of New York, James Monroe Whitmore of Montana. Col. Ollie Reed lies next to his son, 1st Lt. Ollie Reed Jr.

Memory matters. Names matter. The terrible mill of time and distance erases so much. Names begin to rescue individuals from that forgetting. Names can lead us to stories, and stories illuminate how someone acted in events anchored within time, and thus give evidence of his existence, and evidence that he counted for something, that he was once like us, the living.

Memory matters. Names matter. The terrible mill of time and distance erases so much. Names begin to rescue individuals from that forgetting. Names can lead us to stories, and stories illuminate how someone acted in events anchored within time, and thus give evidence of his existence, and evidence that he counted for something, that he was once like us, the living.

Inside the open marble chapel this inscription: Think not only upon their passing/Remember the glory of their spirit.

Inside the open marble chapel this inscription: Think not only upon their passing/Remember the glory of their spirit.

Yes, their spirit, but I don’t trust this noble sentence. They are dead. What glory is there for the dead? I would rather try to remember them as fallible men, as men of habitual gestures and open smiles, of secrets and raptures, but especially as men who lived through ordinary days.

We were among the last to leave. Walking along a row of crosses, I started to write down first names only, old names, unfamiliar names: Hudie, Conrad, Scipione, Hottle, Clessie, Nicasio, Basil, Marcel, Elvin, Truitt, Assaph, Anatole, Preston, Ignatius, Marion. Maybe someone who loved them called them to supper by those names as dusk fell, and they walked into their homes, hungry and full of their tales of the day.

* http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/FWWcasualties.htm

# http://weblog.blogads.com/2003/09/22/french-casualties-in-wwi/

** D-Day, Anthony Beevor ## http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=112&t=171126