In Paris on the last day of our visit, I stood, transfixed, in a small, dark room, six or seven galleries into the museum, in front of softly lit display cases. In my notebook I could only think of verbs – hack, pierce, smash, crush, rend, blast, gut, slice. In this dim light, the gleaming evidence all around me suggested that we are a species that willingly plunges into blood.

In Paris on the last day of our visit, I stood, transfixed, in a small, dark room, six or seven galleries into the museum, in front of softly lit display cases. In my notebook I could only think of verbs – hack, pierce, smash, crush, rend, blast, gut, slice. In this dim light, the gleaming evidence all around me suggested that we are a species that willingly plunges into blood.

I have never seen so many daggers and knives, bayonets and dirks, swords and lances and spears — a dagger with a carved wolf’s head in ivory as its handle; suits of armor for men and horses, made of leather and gold, textiles and iron, beautiful as cut jewels; more shapes and sizes of cannons and artillery pieces that I could have imagined; swords for thrusting, swords heavy enough that to weild them required two hands and a strong back; rifles with barrels 15 feet long; re-curved, compound and long bows, cross bows with bolts as long as my forearm; pistols bent like exercises in geometry, pistols with three barrels, on and on, objects lethal and ornate, utilitarian and beautiful.  Weapons from pre-history, from China and Japan, from Africa and the Pacific Islands, from the New World, from Vikings, Crusaders, Samurais, Grenadiers, Cossacks, Dragoons, Saracens, and Knights, Native Americans and Conquistadors. There were tanks too, a Renault FT and a British Sten, a ball turret from a B-17 and a V-1 rocket suspended above our heads. We drifted through room after room of uniforms and helmets and enough armor to outfit a Company, and portraits of French Generals, stylish Calvary Officers, thoughtful looking 7 foot high renditions of Napoleon’s Marshalls, and in one large case at the end of a hall the Emperor’s Horse, white, stuffed and looking a bit threadbare. After a while I just staggered on, overwhelmed.

Weapons from pre-history, from China and Japan, from Africa and the Pacific Islands, from the New World, from Vikings, Crusaders, Samurais, Grenadiers, Cossacks, Dragoons, Saracens, and Knights, Native Americans and Conquistadors. There were tanks too, a Renault FT and a British Sten, a ball turret from a B-17 and a V-1 rocket suspended above our heads. We drifted through room after room of uniforms and helmets and enough armor to outfit a Company, and portraits of French Generals, stylish Calvary Officers, thoughtful looking 7 foot high renditions of Napoleon’s Marshalls, and in one large case at the end of a hall the Emperor’s Horse, white, stuffed and looking a bit threadbare. After a while I just staggered on, overwhelmed.

In the attic, under glass, we found vast landscape models of French forts and towns. They stretched out on tables over 40 and 50 feet square. Lovingly constructed by artisans in the 17th and 18th centuries, they gave a three dimensional, aerial view of strategic points in the La France.

The Musee d’Armee is located in the Hotel des Invalides, Louis XIV’s grand home for the wounded and old soldiers who had served him in his European wars. Its four wings look into a large, cobblestoned center square.  We walked out of one wing and into a flurry of activity.

We walked out of one wing and into a flurry of activity.  Members of the French Armed Forces were arraying themselves in formation for a ceremony. The French Foreign Legion, the Troupes de marine, the Chasseuers Alpins in their white snow outfits and tarte, their wide beret. All of them carried Famas assault rifles. Thirty French Fireman, axes on their shoulders and clad in red helmets, stood at attention on the far end. At least 20 war dogs, big German Shepherds and Belgian Malinois, and their handlers stood in a double line. One of their own, sitting next to its handler across the square was to receive a decoration. The Brass arranged themselves in lines next to two rows of seats occupied by mothers, wives and children, some in mourning colors.

Members of the French Armed Forces were arraying themselves in formation for a ceremony. The French Foreign Legion, the Troupes de marine, the Chasseuers Alpins in their white snow outfits and tarte, their wide beret. All of them carried Famas assault rifles. Thirty French Fireman, axes on their shoulders and clad in red helmets, stood at attention on the far end. At least 20 war dogs, big German Shepherds and Belgian Malinois, and their handlers stood in a double line. One of their own, sitting next to its handler across the square was to receive a decoration. The Brass arranged themselves in lines next to two rows of seats occupied by mothers, wives and children, some in mourning colors.

I asked an older Frenchman to help me understand what I was

watching. He looked so sorrowful. He said that medals and decorations for valor, that was the word he used, “valeur,” were to be awarded to some members of battalions returning from Afghanistan. He gestured toward the row of seated women and shook his head.

A French Military band entered the square through the narrow archway. One drummer had been standing directly in front of me, balancing on one foot, rigid, waiting. When the band marched in, he began tapping out a staccato, martial theme. Joined by the other drummers, they now all tapped into the same rhythm and speed, a syncopated beat that echoed off the walls. The spectators gathered all around the outside walkways of the Musee square stiffened. The four sides of the square were now filled with soldiers. The band began the La Marseillaise. A woman in a dress uniform standing next to me saluted and turned her head to shush noisy schoolchildren. I placed my hand over my heart, and I looked at all

A French Military band entered the square through the narrow archway. One drummer had been standing directly in front of me, balancing on one foot, rigid, waiting. When the band marched in, he began tapping out a staccato, martial theme. Joined by the other drummers, they now all tapped into the same rhythm and speed, a syncopated beat that echoed off the walls. The spectators gathered all around the outside walkways of the Musee square stiffened. The four sides of the square were now filled with soldiers. The band began the La Marseillaise. A woman in a dress uniform standing next to me saluted and turned her head to shush noisy schoolchildren. I placed my hand over my heart, and I looked at all

the assembled men and women. The French Minister of Defense covered in a dark raincoat stood in the mist, and when the National Anthem had been completed, he reviewed the soldiers. He kept his back very straight.

I would not photograph the seated women, some wearing dark veils over their faces. I could only see their backs. One held the hand of her little girl who seemed entranced by everything, but especially by the big brown and black muzzled Shepherd quietly sitting near her. We left before the speeches began and walked to Napoleon’s Tomb.

I would not photograph the seated women, some wearing dark veils over their faces. I could only see their backs. One held the hand of her little girl who seemed entranced by everything, but especially by the big brown and black muzzled Shepherd quietly sitting near her. We left before the speeches began and walked to Napoleon’s Tomb.

Like a Russian nesting doll, the great man lies submerged within six sarcophagi, the visible one an immense red porphyry scrolled monstrosity as big as a truck. It rests under the center of the Dome Church in the Invalides. The names of some of his battles encircle it — Friedland, Jena, Austerlitz, Moscow, Warsaw, Rivoli, the Pyramids, Marengo. This is meant to be a glorious circle, but we have just walked away from a ceremony replete with live warriors and the loved ones of the dead. I cannot buy into this celebration, one meant to be eternal I suppose. His army invaded Russia with 650,000 men. He returned with less than 100,000. He lost 500,000 men in Spain. Tolstoy understood him: At the same time there was in France a man of genius — Napoleon. He defeated everybody everywhere — that is, he killed a lot of people — because he was a great genius. And he went off for some reason to kill Africans, and he killed them so well, and was so cunning and clever, that, on coming back to France, he ordered everybody to obey him. And everybody obeyed him. Having become Emperor, he again went to kill people in Italy, Austria, and Prussia. And there he killed a lot (1181). * Goya showed what his army left behind. Victor Davis Hanson delivers this verdict: “Paul Johnson’s polemical Napoleon … is not impressed with the little corporal or anything he did. After all, the military record is unquestioned—17 years of wars, perhaps six million Europeans dead, France bankrupt, her overseas colonies lost. And it was all such a great waste, for, as Johnson shows, when the self-proclaimed tête d’armée was done, France’s “losses were permanent” and she “began to slip from her position as the leading power in Europe to second-class status—that was Bonaparte’s true legacy.” **

Like a Russian nesting doll, the great man lies submerged within six sarcophagi, the visible one an immense red porphyry scrolled monstrosity as big as a truck. It rests under the center of the Dome Church in the Invalides. The names of some of his battles encircle it — Friedland, Jena, Austerlitz, Moscow, Warsaw, Rivoli, the Pyramids, Marengo. This is meant to be a glorious circle, but we have just walked away from a ceremony replete with live warriors and the loved ones of the dead. I cannot buy into this celebration, one meant to be eternal I suppose. His army invaded Russia with 650,000 men. He returned with less than 100,000. He lost 500,000 men in Spain. Tolstoy understood him: At the same time there was in France a man of genius — Napoleon. He defeated everybody everywhere — that is, he killed a lot of people — because he was a great genius. And he went off for some reason to kill Africans, and he killed them so well, and was so cunning and clever, that, on coming back to France, he ordered everybody to obey him. And everybody obeyed him. Having become Emperor, he again went to kill people in Italy, Austria, and Prussia. And there he killed a lot (1181). * Goya showed what his army left behind. Victor Davis Hanson delivers this verdict: “Paul Johnson’s polemical Napoleon … is not impressed with the little corporal or anything he did. After all, the military record is unquestioned—17 years of wars, perhaps six million Europeans dead, France bankrupt, her overseas colonies lost. And it was all such a great waste, for, as Johnson shows, when the self-proclaimed tête d’armée was done, France’s “losses were permanent” and she “began to slip from her position as the leading power in Europe to second-class status—that was Bonaparte’s true legacy.” **

I regard individual honor and courage as admirable and essential. I stand amazed and struck into worshipful silence in acknowledgement of Lincoln’s terrible sorrow, and I respect the shattering realism of Sherman and the careful management of Eisenhower. These were men who cared for thei rsoldiers and who retained their humanity in the course of necessary horrors, but Napoleon’s meglomania and all celebration of it leave me detached and cold. I felt more in watching Frenchmen and women in uniform,

rifles in a sling and pointed to the floor, walk the airport in triangle formation, utterly alert to any possibility of threat, doing their duty, protecting the innocent.

War found a way to enter each of our fifteen days in France. In Versailles Napoleon paid us his first visit. An exhibit has been mounted of paintings illustrating (glorifying) his battles: Napoleon’s Wars: Paintings from Versailles These are huge battlefield paintings, many of them easily 30 feet long by 15 to 18 feet high. The flurry of battle rages in their centers, or Napoleon, glowing like a deity, gives his orders. Their edges are more interesting though. It always helps to look at the boundaries of such work — that is where individual, human drama takes place — images of forlorn prisoners being taken, dead men being looted, executions occurring, all the detritus of war.

War found a way to enter each of our fifteen days in France. In Versailles Napoleon paid us his first visit. An exhibit has been mounted of paintings illustrating (glorifying) his battles: Napoleon’s Wars: Paintings from Versailles These are huge battlefield paintings, many of them easily 30 feet long by 15 to 18 feet high. The flurry of battle rages in their centers, or Napoleon, glowing like a deity, gives his orders. Their edges are more interesting though. It always helps to look at the boundaries of such work — that is where individual, human drama takes place — images of forlorn prisoners being taken, dead men being looted, executions occurring, all the detritus of war.

Driving out of Chartres through flat fields of mustard I thought, “This is perfect tank country.” It was liberated by Patton’s Third Army, his Sherman Tanks racing over this good ground towards Paris.

We saw armed Knights everywhere. In Dinan, a river city in Normandy still encircled by its medieval ramparts, a statue of a short, pugnacious knight sits astride an armored charger. Bertarnd Du Guesclin’s statue rests in the market square, the long stretch of ground where he defeated an English knight in single combat. Called the “Flail of the English,” he died while on a campaign when he was 66 years old, 66! St Michael striking the serpent appears at Mont Saint Michel. Sword raised for the killing blow, he wears a serene expression of utter certainty.

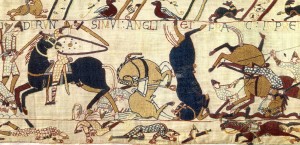

In Bayeux we walked the circuit of the tapestry; its narrative is cinematic, and its rendition of the the Battle of Hastings is convincing. Eyewitnesses to edged weapon battle spoke to the weavers. For example, in one panel we see a mounted soldier wrenched backward at the moment of death, hand on the lance that kills him, his feet leaving the ground. Someone knew what that shock looked like.

In Bayeux we walked the circuit of the tapestry; its narrative is cinematic, and its rendition of the the Battle of Hastings is convincing. Eyewitnesses to edged weapon battle spoke to the weavers. For example, in one panel we see a mounted soldier wrenched backward at the moment of death, hand on the lance that kills him, his feet leaving the ground. Someone knew what that shock looked like.

On Paris streets I found myself looking for easy to miss marble plaques fastened to walls; each one describes events from the Nazi Occupation and the actions of the Resistance. On the Rue Saint Honore this message: Roger Connan/ Fusille Par Les Allemands/ Le 20 Aout 1944 Ans — Roger Connan/ Shot by the Germans/ August 20, 1944/ 28 years of age. Or this: “In this house/ lived/ Alexandre Rochais/ born Aug. 3, 1886/ activist in the 6th section/ arrested June 9, 1943/ murdered/ September 18, 1943/ at Buchenwald.” You cannot travel through France without thinking about war because your eyes cannot escape its continued physical presence on the landscape.

“In this house/ lived/ Alexandre Rochais/ born Aug. 3, 1886/ activist in the 6th section/ arrested June 9, 1943/ murdered/ September 18, 1943/ at Buchenwald.” You cannot travel through France without thinking about war because your eyes cannot escape its continued physical presence on the landscape.

But I know of war only through the calm mediums of novels, histories, memoirs, biographies, movies, documentaries, photographs, and interviews. I know of war through silently listening to veterans tell their stories. I know war vicariously. Therefore I do not know war, really, at all, except as a detached observer. I do not know of its visceral reality, the world beyond this civilian world that only veterans of combat understand. No wonder so many are silent with noncombatants. How can they formulate a new language to tell us, the curious and chaste, what those like themselves have felt?

From observation I know that war is all contradictions — think of the visual and kinetic pleasure of a good weapon, an M1 rifle or a Roman Gladius, and then imagine the nauseous horror of squashed bodies of men and horses on some muddy flat of gray land. Both images call forth our aesthetic sense, and in deeper regions, our moral awareness. Some Union survivors of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg said afterward that the line of Pickett’s 15,000 men in that late July sunshine, their bayonets catching the light, remained the most beautiful sight of their lives. “A member of Patton’s staff in Sicily wrote to his wife: ‘And speaking of wonderful things … perhaps the most beautiful as well as satisfactory sight I have ever beheld was a flaming enemy bomber spattering itself and its occupants against the side of a mountain. God, it was gorgeous (116).'” # Both reveal knots of blood-lust, a delight in spectacle and an electric aliveness.

Now step towards the darkest physical and psychological horrors: Siegfried Sassoon, a lieutenant in the British Army in WW I, coming into a front-line trench at night: “I, a single human being with my little stock of earthly experience in my head, was once again entering the veritable gloom and disaster of a thing called Armageddon. And I saw it then, as I see it now — a dreadful place, a place of horror and desolation which no imagination could have invented.” @ In the paintings at Versailles and in the objects displayed at the Musee d’Armee, in the stories of Iraq told to me by returning students, in the stories told to me by an old man, a gunner who flew in a B-17 over Germany, the flesh of bodies, the stability of minds, the very person we are when we speak and smile — on the battlefield, all of these are ephemeral and vanish into mist and spots when overwhelming force is applied.

But to paraphrase Whitman, war contains multitudes, including love. Again Sassoon speaking for warriors of all ages: “… I was rewarded by an intense memory of men whose courage had shown me the power of the human spirit — that spirit which could withstand the utmost assault. Such men had inspired me to be at my best when things were very bad, and they outweighed all the failures. Against the background of war and its brutal stupidity those men had stood glorified by the thing which sought to destroy them….”

This is all so little to say for there is too much to feel and too much to tell. Nothing I write can capture all the welter of emotions that rose up in me when bloody History took over the day. And I have not told you about this — I have been circling and circling towards Normandy, the center of the trip, and toward Omaha Beach and its blue waters.

* War and Peace: Leo Tolstoy; the Pevear, Volokhonsky Translation

** Victor Davis Hanson: “The Little Tyrant: The Claremont Institute

# James Hillman: A Terrible Love of War

@ Siegfried Sassoon: Memoirs of an Infantry Officer