I will tell you all the stories. I will do my best to describe the sights and sounds. First though, there is this – come to France. Come to Paris. This is the real thing. Do not let excuses as to why you cannot do so dominate you. Bat them away. Come and walk in the Marias du Parc in Normandy in a green landscape Corot could still paint.

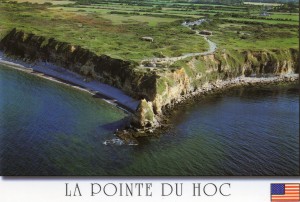

Come walk down the Rue Saint-Honore in the 1st arrondissement and find two dozen couples dancing the tango under a glass roof in the open air. Come to France. Come to Paris. Come to Pont du Hoc where the Rangers climbed cliffs under Wehrmacht machine gun fire, and the tears will well up in your eyes. Come and take your rest in the green chairs circling the East Pond in the Jardin des Tuileries. This is the real thing. Venir en France. Venir à Paris. Changer votre vie.

Come walk down the Rue Saint-Honore in the 1st arrondissement and find two dozen couples dancing the tango under a glass roof in the open air. Come to France. Come to Paris. Come to Pont du Hoc where the Rangers climbed cliffs under Wehrmacht machine gun fire, and the tears will well up in your eyes. Come and take your rest in the green chairs circling the East Pond in the Jardin des Tuileries. This is the real thing. Venir en France. Venir à Paris. Changer votre vie.

I was stuffed into an economy class seat between an unmoving, jittery eyed brunette and Klaus. I don’t know what his name was but he looked like a Klaus to me – small, thin, a beard lining his jawline and rising to a thin mustache, big wire-rim glasses and thinning gray hair pulled back into a tiny ponytail. An American expat living in Vienna, he was returning from Arizona where he had helped his ancient parents move. He was anxious to be home, afraid he would be late for his connection. He missed his wife. My wife, Patti, sat twenty seats behind me.

Klaus was a writer and had stopped in Washington to get a copy of a document he needed from the National Archives, but he evaded my questions about the subject of his writing. It was hard anyway to hear him over the constant thrumming white noise of the engines and air recycling systems. While he tossed back two glasses of wine, he told me a story about an Aeroflot flight he had taken recently from Moscow to Bangkok that grew more deranged with each aerial mile. The passengers began drinking vodka as soon as they left the departure gate. By the time the plane had finished climbing, they were tossing pillows and magazines and occasionally a full bottle back and forth, up and down the aisles. The stewards tried to keep order with threats only to be driven back to their galleys by counter-threats and wildly inventive cursing. With that Klaus turned off his overhead light, propped a red pillow against the bulkhead and fell asleep.

Klaus was a writer and had stopped in Washington to get a copy of a document he needed from the National Archives, but he evaded my questions about the subject of his writing. It was hard anyway to hear him over the constant thrumming white noise of the engines and air recycling systems. While he tossed back two glasses of wine, he told me a story about an Aeroflot flight he had taken recently from Moscow to Bangkok that grew more deranged with each aerial mile. The passengers began drinking vodka as soon as they left the departure gate. By the time the plane had finished climbing, they were tossing pillows and magazines and occasionally a full bottle back and forth, up and down the aisles. The stewards tried to keep order with threats only to be driven back to their galleys by counter-threats and wildly inventive cursing. With that Klaus turned off his overhead light, propped a red pillow against the bulkhead and fell asleep.

Ahead of me I could see a half-dozen movies playing on seat screens. Most of the cabin was dark. We were flying east into onrushing night.

I could not sleep so I read. When I travel, I always carry a book that has nothing to do with my destination. When we drove through Wyoming and Montana in the fall, I read about the history of darkness and night. I want to see all the new things with my eyes first. I want to keep my eyes fresh. I want the new to open to me first.

I could not sleep so I read. When I travel, I always carry a book that has nothing to do with my destination. When we drove through Wyoming and Montana in the fall, I read about the history of darkness and night. I want to see all the new things with my eyes first. I want to keep my eyes fresh. I want the new to open to me first.

At 35,000 feet, I opened up Kerouac’s On The Road, his novel about his wildest elixir – the road and speed and constant movement. He describes his initial trip to Denver and San Francisco, and gives us wonderful visions and stories like the one of the “… Ferris Wheel revolving in the flatlands darkness (23),” and his journey with truck drivers and Irish penniless kids and through to “the ride of his life” on the back of a flatbed truck with no rails and “6 or 7” other vagabonds who all had to lie down or be thrown off. Their drivers, two Minnesota farm boys, roar along at 70 mph and picked up every hitchhiker they see. He zigzagged through Des Moines and Council Bluffs, Omaha and Grand Island, ripped past Shelton and Gothenburg and North Platte and Cheyenne, Wyoming and Longmont, Colorado and into Denver.

When I bring my eyes up, the movies are gone, the white noise louder and no one is moving. I press the computer screen on the back of the seat and my flight information pops up – it is 51 degrees below zero outside. We are hurtling forward at 508 mph, high above the vast Atlantic, hours from shore.

When I bring my eyes up, the movies are gone, the white noise louder and no one is moving. I press the computer screen on the back of the seat and my flight information pops up – it is 51 degrees below zero outside. We are hurtling forward at 508 mph, high above the vast Atlantic, hours from shore.

Like Sal Paradise, the narrator of the novel, I would like to be “… a watcher of the night in jeans…. (31),” but the romance of that part of my youth is gone. I am stuffed into this seat like a bunny in a crate. My legs ache and the brunette on my left in the aisle seat hasn’t moved in hours, sitting straight up in silk like a chic mummy. I don’t even know if she is breathing. I think that maybe I should poke her, but I don’t. Sal says that he “felt like an arrow that could shoot out all the way (27).” Well, yes, I still know how that feels, cramping legs and all. Paris is coming. France is coming. I turn off my light and wait.

Like Sal Paradise, the narrator of the novel, I would like to be “… a watcher of the night in jeans…. (31),” but the romance of that part of my youth is gone. I am stuffed into this seat like a bunny in a crate. My legs ache and the brunette on my left in the aisle seat hasn’t moved in hours, sitting straight up in silk like a chic mummy. I don’t even know if she is breathing. I think that maybe I should poke her, but I don’t. Sal says that he “felt like an arrow that could shoot out all the way (27).” Well, yes, I still know how that feels, cramping legs and all. Paris is coming. France is coming. I turn off my light and wait.