Edward Hoagland, American essayist and novelist, spends each summer in northern Vermont in a farmhouse without electricity. Nothing infringes on his perception of the life of forests and fields except his age. At 81, he writes everyday. He has been one of my faraway teachers since I read The Courage of Turtles in the early 1980’s and felt as if his voice were speaking directly to a thread of vital force in me, my love of animals and the natural world. I have read all his books and have been made happier for doing so and maybe a fraction wiser. No living American writer composes more interesting sentences. He loves animals and human beings and does not give off the misanthropic vibe some nature writers do, the ones who seem to hint that the mass extinction of our species would be a plus.

Edward Hoagland, American essayist and novelist, spends each summer in northern Vermont in a farmhouse without electricity. Nothing infringes on his perception of the life of forests and fields except his age. At 81, he writes everyday. He has been one of my faraway teachers since I read The Courage of Turtles in the early 1980’s and felt as if his voice were speaking directly to a thread of vital force in me, my love of animals and the natural world. I have read all his books and have been made happier for doing so and maybe a fraction wiser. No living American writer composes more interesting sentences. He loves animals and human beings and does not give off the misanthropic vibe some nature writers do, the ones who seem to hint that the mass extinction of our species would be a plus.

When he was young, he worked a circus where he tended the big cats, slept near their cages, and fell in love with elephants. He attended Harvard, has taught at many universities and also knows how to choose paths on New York city streets that avoid muggers’ hiding spots. In Ridge Slope Fox and the Knife Thrower he wrote that “if we like our work, our work will take us all over.” His work has taken him to Africa, the Allagash wilderness of Maine, Manhattan before it became the nesting spot for billionaires, British Columbia, Alaska, into the presence of tigers, bears and wolves, into Yemen and Wyoming, Belize, the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia and all over India, among dogs, within the vagaries of love, to taxidermists, wilderness guides, tugboat captains and Henri LaMothe “who … on his seventieth birthday … dove from a forty foot ladder into a play pool of water twelve inches deep.”* Hoagland has stuttered all his life and come back to sight after falling blind. He has lived the Biblical full life.

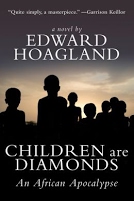

The final sixty pages of Children Are Diamonds, his most recent book, moved me deeply and kept me turning the pages (and those pages are better than anything I have read for months). I can think of nothing else that will keep me as alert to Africa’s tragedies and humanity. He succeeds in moving the reader into an utterly convincing landscape so distant from our soft experience that it could be taking place in another dimension, but yet his characters, even the minor ones who appear for a page and leave, all have recognizable hearts and inhabit their expressions and lives as we do our own.

The final sixty pages of Children Are Diamonds, his most recent book, moved me deeply and kept me turning the pages (and those pages are better than anything I have read for months). I can think of nothing else that will keep me as alert to Africa’s tragedies and humanity. He succeeds in moving the reader into an utterly convincing landscape so distant from our soft experience that it could be taking place in another dimension, but yet his characters, even the minor ones who appear for a page and leave, all have recognizable hearts and inhabit their expressions and lives as we do our own.

I want you to read his books because they will give you pleasure. Something else too. I would like him to know that all that time spent coming to understand wild places and their glorious beasts, and in bringing to light the enthralling grace of ordinary human beings, all that time pouring out his heart,** has given his 81 years meaning and made them beautiful.

**He believes that “a writer’s job is to pour his heart out.” From the essay The Job Is To Pour Your Heart Out