New York City in the 1970’s, Victorian London (especially in the time of the Ripper, the 1880’s), and the Moscow of today have long captivated my imagination. I visited New York often in the 70’s and learned at least the rudiments of street awareness there, Dickens’ and Stevenson’s London have left indelible images in my imagination and Arkady Renko’s Moscow is described by Smith in seven novels detailing the police detective’s efforts to do his job honestly and avoid being destroyed by corruption.

New York City in the 1970’s, Victorian London (especially in the time of the Ripper, the 1880’s), and the Moscow of today have long captivated my imagination. I visited New York often in the 70’s and learned at least the rudiments of street awareness there, Dickens’ and Stevenson’s London have left indelible images in my imagination and Arkady Renko’s Moscow is described by Smith in seven novels detailing the police detective’s efforts to do his job honestly and avoid being destroyed by corruption.

The Moscow of Renko in Three Stations is a city dominated by wealth and Putin’s influence, one where billionaires ride past gangs of homeless children, prostitutes and ordinary citizens like gods in armored sedans, but frightened gods, all too aware that Putin is always the first among all and can take everything away when he chooses. I read Smith for his detailed knowledge of a place I will probably never visit and will certainly never know as he does, a dangerous world where Renko coolly handles all manner of threats. He keeps hold of his patience and honor and refuses to buckle to authority, but also is smart enough to use irony rather than confrontation in many tight spots. The villains in Three Stations are predators perfectly at home with their nasty selves. They don’t wrestle with the moral qualities of their actions.

In New York, dodging pushers and whores and slit-eyed kids on 42nd street, walking along a noir-ish 10th Avenue where large shadows stepped out onto the sidewalk and then slipped back, riding a subway into the Bronx in the early morning hours, I felt a certain stupid thrill that comes only in being that young and immortal. My friends and I skirted the edges of trouble, both lucky and at least wise enough not to push that luck too far. We did not have to imagine the sense of menace we felt. It was there all around us.

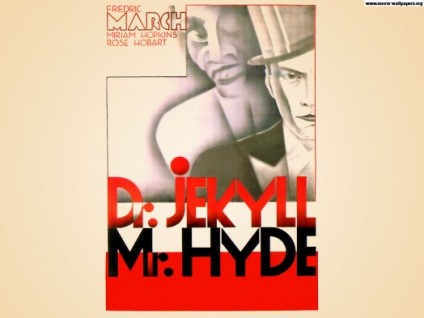

Echoes of that New York can be found in Stevenson’s descriptions of the London cityscape, the insights into the social relationships of the time and in Hyde, a man who from the beginning is described as possessing “…the haunting sense of unexpressed deformity” (Jekyll is a ghost; Mr. Utterson, the narrative voice of much of the book, is more of a presence).

Hyde enjoys the ultimate hiding place for a criminal, within the skin of a most respectable doctor who yearns for the freedom to act in unrespectable ways (what he wants to do is never spelled out – we get the usual Victorian euphemism of ‘depravity’; our 21st century uncensored media can show us all the kinds of ugliness that will fit into that box).

Jekyll discovers a potion that will unleash the other self that he argues resides within all of us, the amoral killer who lives cocooned within the good man. When a Dr. Lanyon witnesses the Jekyll to Hyde transformation, he pronounces that “…my life is shaken to its roots.” Hyde boasts that “…your sight shall be blasted by a prodigy to stagger the unbelief of Satan.”

Jekyll discovers a potion that will unleash the other self that he argues resides within all of us, the amoral killer who lives cocooned within the good man. When a Dr. Lanyon witnesses the Jekyll to Hyde transformation, he pronounces that “…my life is shaken to its roots.” Hyde boasts that “…your sight shall be blasted by a prodigy to stagger the unbelief of Satan.”

Most of the images associated with the characters are either absurd or campy, but I do like the Spanish translation.

In Frankenstein Dr. Frankenstein makes the creature (an action initially motivated by his mother’s death) to try to defeat death and end the suffering that accompanies it; this is a utopian dream, and so is Jekyll’s dream of absolute freedom, one unrestrained by morality. Frankenstein’s goal, while equally mad, is at least benign. Jekyll’s goal is wholly selfish and nihilistic, a fantasy of “vicarious depravity”.

A release from responsibility is critical to the fulfillment of this dream. Describing Hyde’s murder of an M.P, he says that “…Hyde alone…was guilty” — I may do anything, but the creature within, a creature morally separate from me, is alone to blame.

Jekyll’s insight into Hyde’s love of that complete freedom helps us understand other acts of the worst kind of criminality and war-time atrocity. He says, “…my lust of evil gratified and stimulated my love of life screwed to the topmost peg.” That idea helps explain war-time killings and torture done by apparently good human beings as well as a psychopath’s self-awarded permission to do anything to another — to be able to do anything and walk away from it, free and free from torment. That is the nightmare wish, but if we are honest with ourselves, a tug we too have felt.

The duality of the self helps to explain the utterly deceitful Iago from Othello and Edmund from King Lear, Jekyll-Hyde, maybe even the criminal side of Gatsby, the one that sold bad alcohol in storefronts, practiced fraud and used Wolfsheim’s hired thugs to shut down his mansion when he began his affair with Daisy, but Jekyll proposed another possibility, one that seems to have more in common with contemporary theories of personality: “…man will ultimately be known for a mere polity of multifarious, incongruous and independent denizens.” I have felt the presence of these kin, only faintly (thankfully), but I have witnessed their emergence in others too. Maybe Hyde is primarily a persona of youth, a period when we are more impulsive, uncertain of who we are, quick to anger and act based on that anger. I have stories from my young manhood that I have never told another because I remain ashamed of what I had done — events that showed me that I could never think of myself as innocent or beyond corruption, and that my harmless face also carried a stranger on the other side.