Forty one years ago my geology professor found me in his classroom in the early evening after I had finished cleaning it. I was reading his notes one more time from that day’s lecture. His grumbly, bear-like growly delivery about the movements of the earth had found something in me. I had been captivated. I was standing in front of a board, my arms folded, a bucket at my feet, looking at his drawing of mountain building. I don’t know how long he had been watching me, but from the back of the room his deep voice suddenly spoke. He said something along the lines of, “You like this don’t you?”

I cleaned classrooms in the science building every weekday afternoon; afterwards, he would sometimes invite me into his office to talk about geology, history, his past, his family. I mostly listened. He went so far as to invite me to his home for dinner and introduce me to his daughter, my age and pretty. He retired a year later and died soon after.

I clearly remember one story he told me: A young man, he was doing Ph.D. work somewhere out west among dry mountains miles removed from anything. I don’t remember if he told me the location. If he did, I have forgotten.

He had been working all afternoon collecting samples from a cliff face, cracking at it with his rock hammer, holding pieces up to his eyes where he examined them with a fold-up magnifying glass he kept on a string around his neck. He spoke of how focused he had been, of how quiet had settled all around him “as if he was in a bubble,” he said. He remembers stepping away and standing up straight, stretching his back, looking up. He heard rocks falling to his left, chipping down and clattering. Then, maybe fifty or sixty feet away, an enormous overhang collapsed, and a shelf of rock smashed into the ground. Dust rose. The tremendous sound retreated. He stood rooted, disbelieving, shocked, uninjured.

He stumbled away from the cliff face and sat down. He told me that he was stunned, that he could not think. He did not get up for a long time, but finally he began to smile, to feel exhilarated, for not only had he escaped a random (and ironic) death, but he had seen, first-hand, a pristine geological event. Laughing now, still bemused, he shook his head on finishing. I have always associated that story with something romantic about geology.

In coastal Maine you cannot escape geology, its processes and its present-day offerings. You cannot escape deep time. To understand what you have been scrambling over, to understand the boulders and ledges, the reefs of rock everywhere, you must go back in time.

In coastal Maine you cannot escape geology, its processes and its present-day offerings. You cannot escape deep time. To understand what you have been scrambling over, to understand the boulders and ledges, the reefs of rock everywhere, you must go back in time.

Deep time is unimaginable as fact. For example, I write this term and these numbers: the Permian geological period, 245 to 286 Million Years ago. The name gives it a ranking in time, but those numbers are both a marker and a blur, a measurement we cannot feel. They defy our intuitional senses. We can intellectually and emotionally grasp the space of a year, of several lifetimes even, but then our understanding becomes trickier. We have to revert to metaphor, to pictures, to stories.

So, imagine a series of curving platforms, waist high, encircling you. They are long and wide and filled up with rocks, sand, dirt, mounds filled with fire; rain clouds drift above portions of them. A nameless sea bounds their east coast. Begin to move clockwise, or rather from hundreds of millions of years ago to this moment where you balance on a slanting rock ledge within touching distance of a thread of the Atlantic Ocean.

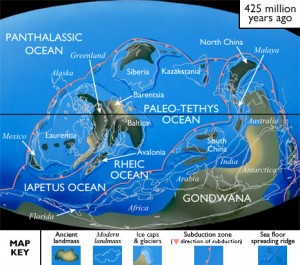

You are in the Silurian period, between 443 and 417 Million Years ago. Volcanoes rise around you. Fiery rocks fall in every direction; weighted clouds of superhot gases plummet

You are in the Silurian period, between 443 and 417 Million Years ago. Volcanoes rise around you. Fiery rocks fall in every direction; weighted clouds of superhot gases plummet  down mountainsides. Lava blankets the earth. The bowl of sky is a backdrop to scenes of massive violence.

down mountainsides. Lava blankets the earth. The bowl of sky is a backdrop to scenes of massive violence.

You stand at the edge of the Iapetus or the Rheic Oceans. Perhaps you can see the fire from the volcanoes on the micro-continent of Avalonia to your east. There is no North American Continent. Our time’s great land masses are in a fetal stage. Geological processes make no guarantee that they will be born. The lava flowing and then cooling all around you as you move your eyes from left to right is one part of rock you will encounter again, though vastly changed.

Microscopic grain by mote by chunk, silt and sand are drifting down through the strange  oceans and packing themselves into layers. The oceans were filled with new life. The bodies of the dead drifted down with the silt. This process goes on and on, as close to a moving definition of infinity as we can see on the planet. The layers compact. The pressure of their weight forces out their water. They solidify and become rock. All this you see.

oceans and packing themselves into layers. The oceans were filled with new life. The bodies of the dead drifted down with the silt. This process goes on and on, as close to a moving definition of infinity as we can see on the planet. The layers compact. The pressure of their weight forces out their water. They solidify and become rock. All this you see.

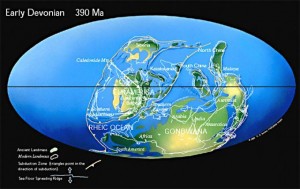

The rock ledges are made up of silt and sand deposited in the Silurian, covered, heated, twisted on end and reformed during the Devonian. They are about 400 MY old.

The rock ledges are made up of silt and sand deposited in the Silurian, covered, heated, twisted on end and reformed during the Devonian. They are about 400 MY old.

Turning, you look at the sweep of the next platform and the Devonian period (-417 to 360MY) and the crushing of the Avalonian continent into the coast of what will become North America, its plate pushing under the North American crust and the resulting pressure sending the Appalachian Mountains splintering upwards to Himalayan heights, snow swirling along its vertebras of crests stretching for thousands of miles (stand on the top of Hawk Mountain today and the rock beneath your feet is only the nub of what once was). You watch the Iapetus Ocean contract, caught between the continents and then, shhhhhh, in vapor and mist it vanishes.

The Mountains’ erosion accompanies their upthrust and vast rivers pour down toward the coast carrying boulders and more sediment. You stoop down by the platform and witness the roaring upheaval both under and above the waves. The layers in the new-aborning Atlantic Ocean grow and are submerged beneath the earth’s surface and there are compressed and turned, heated and remolded and infused with veins of quartz and feldspar. The rock is a living thing, twisting and morphing. Rapt, your eyes have followed the immeasurable changes and slid over onto the platform and folding into the Permian period (-286 to 245MY). All this you see.

You turn to the Mesozoic period (-245 to 66MY). What will become Europe and Africa creak away from your coast, riding their tectonic plates which slide on boiling liquid rock like a vast cushion gliding over grease. The Atlantic Ocean widens. Storms crease and surge through skies filled with lightning. All the titanic forces you have witnessed — the folding and faulting of rocks as if they were potter’s clay, mountains climbing and dissolving, sediments building and solidifying and turning, seas opening and closing, the young planet destroying and creating itself over and over – all of this continues. All this you see.

On the next platform we leap ahead to the late Pleistocene (-1.6MY). You recognize the continents for their present day familiar shapes, but another earth-sculpting force, glaciers almost two miles thick, come grinding down the coast; they contain so much water that the Atlantic Ocean drops 300 feet or more. Today, scientists pound stakes in the path of glaciers to measure their speed, but your vision takes in the passage of millenniums, and you see them smashing everything, covering everything. You watch the earth itself squashed under their incalculable weight.

The last period of intense glaciation, the Wisconsin Episode comes to an end about 10,000 years ago. You watch the ice retreat and

The last period of intense glaciation, the Wisconsin Episode comes to an end about 10,000 years ago. You watch the ice retreat and  water pour from their faces. Lake Agassiz covers all of Maine and Canada and dips all the way down to present day Chicago. Then that lake too dies and finally the coast of Maine as we know it is revealed, stripped, craggy and jagged, the cliffs and ledges on which we walk today open to the air.

water pour from their faces. Lake Agassiz covers all of Maine and Canada and dips all the way down to present day Chicago. Then that lake too dies and finally the coast of Maine as we know it is revealed, stripped, craggy and jagged, the cliffs and ledges on which we walk today open to the air.

One afternoon we climbed onto the ledges closest to the open ocean. The dogs raced from the house to join us; Wolfie, almost perpendicular against a steep face, had to be hoisted up. Facing due east, we saw nothing except the Atlantic, still expanding at the rate of two inches per year. A heavy swell carried big waves toward us. High up, our arms around the dogs, we looked out, enjoying the wind and the vista. The rocks and the sea both seemed permanent, immovably set. Not so, of course. Both are changing with every wave, and the four of us were only as permanent as the sea-spray we watched rising above the white-caps smashing into the base of our perch.

That evening we sat together eating spaghetti and drinking wine, telling stories and laughing, oohing and ahhing at the moonlight spread out in neon patchs on the sea beyond the deck.

A clutch of sunflowers, a crow’s feather, a table, a deck, a scattering of granite flakes — September, 2012