The strain in the chest wall I thought may be my heart expressing a problem so best see the doc who told me about angor animi, “a sense of impending doom,” a medical term that describes the patient’s crushing sense in body and mind that he or she is in danger of imminent death, and a term that sounds about right for the jagged anxieties coursing through the body social and body politic of our Republic.*

The strain in the chest wall I thought may be my heart expressing a problem so best see the doc who told me about angor animi, “a sense of impending doom,” a medical term that describes the patient’s crushing sense in body and mind that he or she is in danger of imminent death, and a term that sounds about right for the jagged anxieties coursing through the body social and body politic of our Republic.*

Eliot was 47 when he wrote that we cannot live with too much reality. After WW I he saw the disfigured Tommies selling pencils on London street corners. He read the pages of names in the casualty figures of the Evening Times. He knew the families of those who never returned from France. In his poems he described the cost of being always beset by the tangible brutality of the real world.

Most of us do not have this experience, but we do live within a ceaseless electric river of violence, and as a consequence, are witness to hearts that have become strained and fearful. We are drowning both in horrific news images and stories, and in games and narratives that pose cruelty as entertainment.

At the same moment as our collective anxieties pour out and take on more extreme forms, our communal understanding of others unlike ourselves is narrowing. We are gathering into smaller tribes. We are making tougher walls behind which we wait.

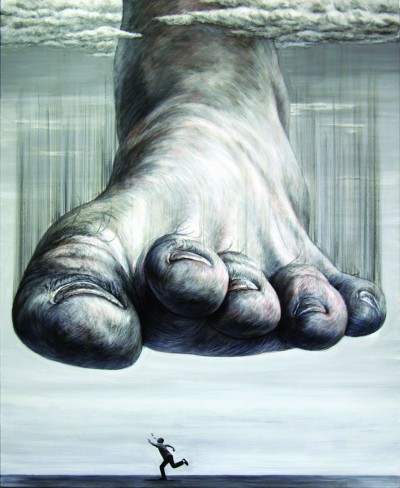

The list of disposable Americans grows longer — working class men and women, the working poor, those who struggle on the margins of wealth, the ones who lay down their hands and bodies to do the work that keeps everything running. The volume of political and media invective directed against the exhausted and powerless has become more shrill and more vile. Do you know any ordinary American adult who is not uneasy, but often silently angry, and who knows that something awful has happened to the gears and levers that helped keep things fair?

The list of disposable Americans grows longer — working class men and women, the working poor, those who struggle on the margins of wealth, the ones who lay down their hands and bodies to do the work that keeps everything running. The volume of political and media invective directed against the exhausted and powerless has become more shrill and more vile. Do you know any ordinary American adult who is not uneasy, but often silently angry, and who knows that something awful has happened to the gears and levers that helped keep things fair?

painting by Nathan Margoni

Forty seven years ago Howlin’ Wolf had a vision, but then he had been born in the Mississippi darkness of 1910 in the aptly named town of White Station. He knew something about how the absolute realness of a desperate life could shape a person:

“Somebody has been cashing checks and they have been bouncing back on us. And these people, the poor class of Negroes and the poor class of white people, they’re getting tired of it. And sooner or later it’s going to bring on a disease on this country, a disease that’s going to spring on from midair and it’s going to be bad. It’s like a spirit from some dark valley, something that sprung up from the ocean …. Like Lucifer is on the earth.”**

Like the animals we are we can sniff the air, we can sense the shift of the zeitgeist, the movement of sinister forces, the onset of “a disease on this country,” Angor animi being its precursor and immune to any known treatments. The wound must be borne.

Yet another felt mass is also present — perhaps the other side of Angor Animi is Angor Dolor (my coined term), the fierce pressure of pity and sorrow, the turn-around to the feeling of onrushing doom, Angor Dolor being a more acute receptivity to the fierce press of the real: what we cannot escape, we take into ourselves. The wounds of others must be acknowledged.

That pressure seems to grow with age or at least feels that way. For me, examples of suffering have become overwhelming in volume, and the sharp edge of their command calls me to their attention. Is it only the necessary cost of growing old that means a scrap of every day must offer a summons in any direction I turn, a call to field the universal question of suffering I cannot escape asking: Why must this happen?

It has become a hard task for me to banish the pictures and incidents which now mix together, the deeply tragic and the momentarily heart-sore: mischance and misfortune and disasters have become more insistent, more present (I am not alone in this I think). The images accumulate like parables I cannot forget: the possum tossed to the side of the road and the perfect fox there too. The light-blind deer, panicked and flurrying between barriers on the Expressway. The stony bird sightless in the scrub below the glass.

The dogs who bear scars of embedded steel collars, teeth marks on their faces, ribs as plain as the ridges above emaciated valleys. The dogs who crouch prepared for the blow, their heads turned away from the human voice or touch.

The child face-down in the wash of the sea, the broken man on the corner shivering by his dog, the lost, the marooned, the desperate.

The child face-down in the wash of the sea, the broken man on the corner shivering by his dog, the lost, the marooned, the desperate.

Those who walk out of deserts, away from annihilation, North.

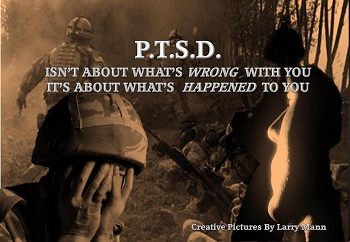

The veterans of the jihadi wars who cannot sleep because dreams of exploding IED’s and dead comrades are worse than exhaustion.

The forgotten, the dispossessed, the women bearing their children above the dust of roads. Any woman, alone, who senses the tremor of men’s slurred speech approaching — thorns in the air, talons scraping along the path.

The forgotten, the dispossessed, the women bearing their children above the dust of roads. Any woman, alone, who senses the tremor of men’s slurred speech approaching — thorns in the air, talons scraping along the path.

Children trapped by gunmen on the corner, in the classroom, in church, walking to the store.

Roethke knew what it feels like to have all these bereavements in your head:

“I think of the nestling fallen into the deep grass,/The turtle gasping in the dusty rubble of the highway,/The paralytic stunned in the tub, and the water rising, —/All things innocent, hapless, forsaken.”#

Does age make us more susceptible to pity? It has for me, but it does not bring me any closer to answering questions about suffering and cruelty except this thought: there are more of us and thus exponentially more suffering, but even that does not hold true — this is not the 20th Century, the era of cataclysmic world wars and genocides. The terrors of this time do not possess those dimensions of slaughter.

Sometimes I feel as if I am careening about the pure darkness of a enormous space, arms extended, aware of echoes, in fear of a void opening beneath my feet.

What response and wisdom is possible beyond accepting that premonitions of calamity and an encompassing pity have tumbled together, a heart-wreckage without resolution?

Only these poor thoughts: that action is better than talk, that one must not give in to helplessness, that despair is the worst sin, that fear can make us into monsters, that no one will rescue us, that we are responsible.

Only that, in spite of my blindness, I must believe in the inherent goodness of my fellow travelers. Only that, in spite of my dread, I must believe that wounds are easier to bear together and the wounds of others easier to see.

*Doc says I have the heart of a forty year old and only clenched and cramped the connective tissue and muscles of my latissimus dorsi and chest wall lifting weights and throwing walnuts for my berserk Borders to chase. They love the arc of targets in the morning.

**from an interview in Open City Magazine, 1968

My wife photographed the fox which she retrieved from the roadside of Route 422.

#The Meadow Mouse

My friend… You wrote, “that action is better than talk, that one must not give in to helplessness, that despair is the worst sin.”

Not only that, but for now, the earth is on our side. Each day, the sun stays up a little longer. The green and the birds will come back. Until then, just breathe, walk out in the cold, and enjoy the moments.