We did not move or speak for minutes after the last shot closed. The credits rolled by. We looked at them, dazed, I think, by the ferocity of what we had just encountered. Why do we feel this way?

We did not move or speak for minutes after the last shot closed. The credits rolled by. We looked at them, dazed, I think, by the ferocity of what we had just encountered. Why do we feel this way?

Movies are an intravenous art: find a vein, the vein that matches your curiosity or an aroused interest. Slide the figurative needle into it and tape it down – you have seated yourself in the twilight; you bring your anticipation with you. The curtains part, the screen fills with light, and images begin adding the seamless, unspooling narrative to the bloodstream, to the eyes, to the brain, where their directness lets us feel just before we think. You are about to see something new. You cannot pause the experience. This is not a book from which you can lift your eyes. Movies roll forward. They carry us with them as if they were ocean currents. In this way movies, the most memorable artistic medium of the late 20th century, capture us. Great movies let us see and feel simultaneously in unbroken moments that stretch into hours, and in this way they entrance and enrage us, bewitch, horrify, delight and concuss us, shock us, and finally provoke our thoughtfulness after the narrative has gone black and the credits finish the spool and around us, the other eyewitnesses rise up and begin to walk, in a daze, toward the exits.

12 Years a Slave is more a documentary than a character investigation or sweeping narrative. Its central character, Soloman Northrup, a free man kidnapped and sold into slavery, along with every other character, is flat rather than dynamic. He endures, and he finds ways to retain his pre-slavery self and dignity, and that may be the point. How could his experience be one where personal growth is the desired end? He does not have the luxury of contemplation. He is too busy staying alive. This is a Dickensian movie. It shows a good man in an iniquitous world and then shows how he journeys through it.

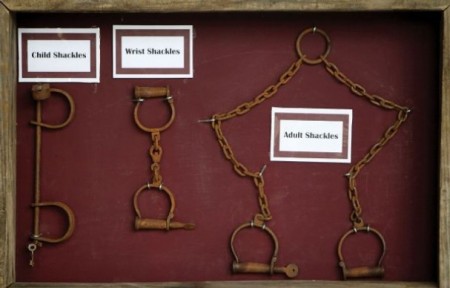

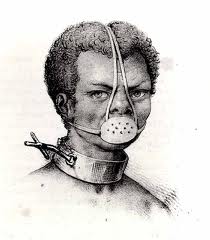

12 Years a Slave recreates a South governed by a spoken, physically enforced and daily imagined status quo of implacable cruelty, one guaranteed by law, religious belief, tradition and color. We witness black men and women and children as they are prodded, slapped, scratched, stand naked, have their teeth inspected as if they were horses, forced into silence by medieval looking stoppers chained to their heads and inserted into their mouths; we watch as they are beaten with wooden paddles, beaten with cat-o’-nine-tails and with bullwhips; as they are kidnapped, torn from their children, torn from those who loved them. As they are sold, and loaned out and sold again, and threatened with being sold. There is no end to the threats. Ever. We are asked to imagine generations of lives

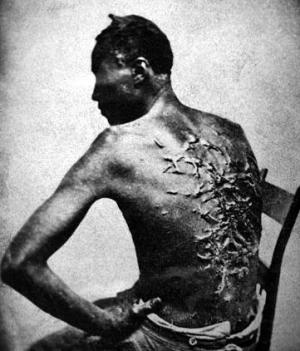

12 Years a Slave recreates a South governed by a spoken, physically enforced and daily imagined status quo of implacable cruelty, one guaranteed by law, religious belief, tradition and color. We witness black men and women and children as they are prodded, slapped, scratched, stand naked, have their teeth inspected as if they were horses, forced into silence by medieval looking stoppers chained to their heads and inserted into their mouths; we watch as they are beaten with wooden paddles, beaten with cat-o’-nine-tails and with bullwhips; as they are kidnapped, torn from their children, torn from those who loved them. As they are sold, and loaned out and sold again, and threatened with being sold. There is no end to the threats. Ever. We are asked to imagine generations of lives  surrounded by threat, stalked by it, and we watch the response to that terrible predatory threat in the gestures, expressions and bodies of the enslaved. We witness the lowered heads, the lowered eyes, the automatic reply of “Suh” to any question from anyone white, the barely muffled anguish as beatings are administered to one of their own. We watch the enslaved retreat inside of themselves as an essential method of survival, the disguises that they must create to foster an alternate reality for their masters, one of an unthreatening illiteracy and submission. We witness in one precise scene, how the weight of one day’s worth of cotton picked by one person comes to illustrate the mechanisms by which one race of human beings brutalized another in the name of profit. We watch kicks delivered to chests and ribs and buttocks. We witness the rapes. We witness the murders by rope and knife. We watch the despair and the endurance of the enslaved, and the entitlement to cruelty claimed by their owners, as if their pitilessness and their willed, dogmatic blindness made up the vital oxygen necessary for their lives to have meaning.

surrounded by threat, stalked by it, and we watch the response to that terrible predatory threat in the gestures, expressions and bodies of the enslaved. We witness the lowered heads, the lowered eyes, the automatic reply of “Suh” to any question from anyone white, the barely muffled anguish as beatings are administered to one of their own. We watch the enslaved retreat inside of themselves as an essential method of survival, the disguises that they must create to foster an alternate reality for their masters, one of an unthreatening illiteracy and submission. We witness in one precise scene, how the weight of one day’s worth of cotton picked by one person comes to illustrate the mechanisms by which one race of human beings brutalized another in the name of profit. We watch kicks delivered to chests and ribs and buttocks. We witness the rapes. We witness the murders by rope and knife. We watch the despair and the endurance of the enslaved, and the entitlement to cruelty claimed by their owners, as if their pitilessness and their willed, dogmatic blindness made up the vital oxygen necessary for their lives to have meaning.

A punishment collar.

We watch the owners and the overseers – a more benevolent one, indifferent ones, the sadists, the protective, the truly mad and their wives brim full of hatred for the raped women. We see how the everyday, never-hidden reality of slavery corrupted economics, religion, marriage, hearts, the law, and the family. In his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass describes the terrible convolutions that emerged from the sexual depredations of slavery: “The master is frequently compelled to sell [his mulatto children] out of deference to the feelings of his white wife; and cruel as the deed may strike …one, for a man to sell his own children to human flesh-mongers, … unless he does this, he must [either] whip them himself, or must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but a few shades darker complexion  than himself, and ply the gory lash to his naked back; and if he lisp one word of disapproval, it is set down to his parental partiality, and only makes a bad matter worse, both for himself and the slave whom he would protect and defend (5).” The master, by standard practice, has already ignored the natural bonds of human feeling in the enslaved. Now that merciless indifference must pass on to him like a curse from which he and his family cannot free themselves. Slavery blighted everything it touched.

than himself, and ply the gory lash to his naked back; and if he lisp one word of disapproval, it is set down to his parental partiality, and only makes a bad matter worse, both for himself and the slave whom he would protect and defend (5).” The master, by standard practice, has already ignored the natural bonds of human feeling in the enslaved. Now that merciless indifference must pass on to him like a curse from which he and his family cannot free themselves. Slavery blighted everything it touched.

The back of Peter, a man enslaved in Louisiana.

Movies made in 1932 or 1944, 1976, 2001, or any year must also be seen in a present context. The nature of all art is to time travel. 12 years a Slave brought forth an historical cascade of associations for me — the great movie Glory, the lacerating, unforgettable poem “Middle Passage“, John Lewis and so many Freedom Riders beaten in an Alabama parking lot, Martin Luther King refusing to back down time and time again. That list goes on and on in my imagination.

We are beset by all manner of media dreck and decadence, by so much vulgar ephemera. A morally serious, well-made, movie such as 12 Years a Slave has the power to blow all of that gunk and mire away. The strength of its story remains with you for days. Soloman Northrup’s suffering and his resolute spirit remains with you. Go see for yourself. Witness and watch. Please.