I always watch their faces when they slip the needle into the vein; I don’t care to watch the stick, and their expressions are usually such wonderful studies in professional ease and concentration.

At 6 in the morning, Kofi continued to answer my questions as he took my blood, but in beginning he told me that I was his first client and this arm his first arm and then he smiled and said, “I’m just messin’ wit you.”

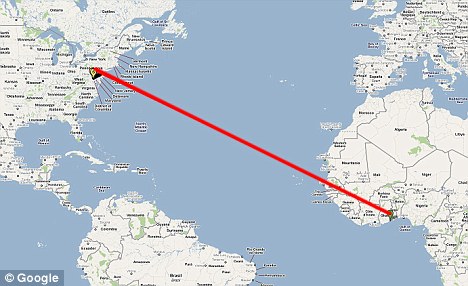

He had been in the US for three years and had been a med-tech for eight months. He had not been home to his native Ghana in all that time. He told me how much he liked the cool temperatures of the fall here, and that when he returned to Ghana for a visit, he would have to “stay indoors because it will be too hot for me.” He missed his mother and sisters and his friends. I told him that I had been a teacher; he said that he often thought of his best teacher, Mr. Amingo (sp?), who had taught him science and math, and that he would visit him upon his return. We spoke for as long as it takes to draw three vials of blood and tape on a patch.

He had been in the US for three years and had been a med-tech for eight months. He had not been home to his native Ghana in all that time. He told me how much he liked the cool temperatures of the fall here, and that when he returned to Ghana for a visit, he would have to “stay indoors because it will be too hot for me.” He missed his mother and sisters and his friends. I told him that I had been a teacher; he said that he often thought of his best teacher, Mr. Amingo (sp?), who had taught him science and math, and that he would visit him upon his return. We spoke for as long as it takes to draw three vials of blood and tape on a patch.

I love these moments when previously unknown lives blossom out right in front of me. They give me hope for humanity as a whole. I have constructed a kind of Rube Goldberg Faithfulness System — because I can see so vividly one stranger’s ordinary dignity,* I make the unremarkable leap to most of the people I have known who, for all their dissimilarities, also possessed such dignity. Then I make a final leap of faith into the anonymous billions who live in the present, and with the exceptions of those who embrace malignant ideologies, or who choose the grotesqueries of unbridled power, ambition and greed, I thus affirm a belief in the essential grace-full-ness of most human beings.

I could not live away from people; I lack the misanthropic gene. I lack the hermit itch. Leave out the mean, the fanatical and the consistently pessimistic, and I will happily talk to anyone. I can listen to their stories for hours.

Yet, a relentless gregariousness also makes me crazy, especially in a crowd. If I cannot escape it, it starts to resemble so much jibber-jabber. I become bored and then snarly. If unconstrained, I begin to drift toward any place quiet. Soon the drift becomes a lope and_I’m_away, and the very act of walking begins to take away my quarrelsome blues.

Little Eva caught the feeling when she sang, “Do it nice and easy now, don’t lose control/a little bit of rhythm and a lot of soul/Come on baby, do the Loco-motion.” The heel strikes and the body swings forward and the next foot comes down, and eyes up all around the world rolls at a slow enough speed to catch its sensuous details – the opulent slant of light along Madison Avenue at 4 on a winter’s afternoon, the deep red color of a hawk’s tail feathers glimpsed in its low spiral.

I think my father’s greatest fear was to be confined. He loved to walk – in the old neighborhood, on the golf course, through woods with his grandchildren. I am my father’s son. It’s all about soul for “you got to move!” For both of us, placing one foot in front of another under the sky was and is equivalent to a delivery of a short-term blessing. I walk, therefore I am alive.

Put me on a trail, on a deserted beach, above timberline under an omnipresent sun, on a long curve of meadow, climbing a path up through trees, on a quiet road next to fields. Let it rain or snow or the wind howl like devils or blue sky break out as if we were walking in Oz – I don’t care as long as I’m out and racing along with my silly dogs who so graciously never jibber-jabber.

Put me on a trail, on a deserted beach, above timberline under an omnipresent sun, on a long curve of meadow, climbing a path up through trees, on a quiet road next to fields. Let it rain or snow or the wind howl like devils or blue sky break out as if we were walking in Oz – I don’t care as long as I’m out and racing along with my silly dogs who so graciously never jibber-jabber.

Late last Thursday afternoon Wolfie took off from the surf and ran in a straight line toward a lone, short haired woman sitting in a beach chair near the dunes. He would not listen. When he came up on her, he stopped and lay down at her feet. I ran up behind him, apologizing, Luna hurrying behind me.

She was delighted. Her husband was at home; she was from Linwood, NJ and her kitten had died suddenly in May of kidney disease. She missed her. The traffic was too busy on their street; she was fearful of adopting another kitten. She stroked Luna as she spoke, and she smiled. We never exchanged names. Our names seemed unimportant. She told me her story. Luna tunneled in the sand under her chair. I listened and came to like her. I knelt on one knee facing her and the Atlantic. South and west and 5000 miles away the night life in Accra was starting to roar, but here I could not see another person, not for miles.

*which is never ordinary