Light moves faster than the eye can follow. James Turrell works in light. He creates spaces filled with light, both natural and artificial. He bathes his audiences in every shade. He immerses them in fluctuating arrays. That is how I first imagined Molly Bloom’s 36 page soliloquy – a fluid range of light of boundless tones. Language as light. Language felt upon the skin and as a direct infusion into the eye. I have read the soliloquy and listened to it. Listening catches the shifts, catches the moods fading and being replaced, abruptly springing into focus, plunging, languorously stretching out. Molly’s voice#captures what it feels like to listen to sinuous, spinning streams of light.

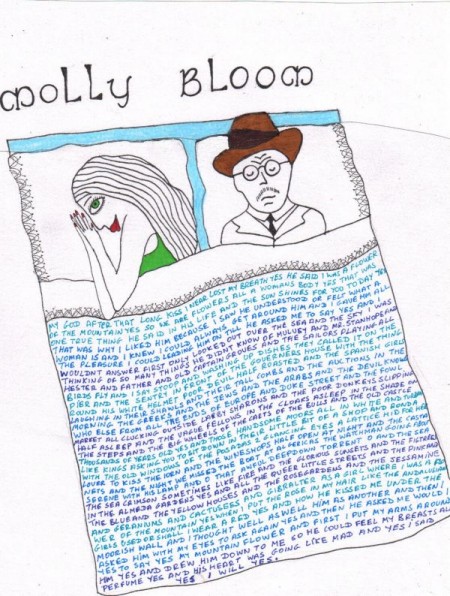

Late at night, ending the day of June 16, 1904, Molly lies in her bed at 7 Eccles Street in Dublin, restless, dozing, awakening, reimagining scenes from the day and her youth, beginning her period, using the toilet, waiting for Leopold. She thinks of tea, sex, murder, the vagaries of men, feet, hands, priests, lingerie, losing weight, her daughter, Milly; the heat and beauty of her young woman hood on Gibraltar, seedcake, flowers and more flowers and music. She muses over her many men and their attributes. Hers is an erotic sensibility: “I like a new fella every year,” and in speaking about acquaintances who think of themselves as superior,”I knew more about men and life at 15 than they’ll know at 50 (627)” She passes over gossip. She sings. She  complains. She remembers with renewed longing. She listens to the whistling of trains passing in the distance. Hers is a meditation made of everything we might smell, linger over with our eyes, touch, taste, desire, feel, instinctively repulse, and instinctively embrace. Molly is a singer, an adulteress, a mother of a 15 year old daughter, a wife, the mother of a dead son. She is scornful of all pretention, alternately hard-headed and romantically yearning. Left alone all day by ‘Poldy’, she is lonely, possessive of him and mourns the splintering of their marriage by the death of Rudy, eleven years before this day who she recalls burying “in his little wooly jacket (642).”

complains. She remembers with renewed longing. She listens to the whistling of trains passing in the distance. Hers is a meditation made of everything we might smell, linger over with our eyes, touch, taste, desire, feel, instinctively repulse, and instinctively embrace. Molly is a singer, an adulteress, a mother of a 15 year old daughter, a wife, the mother of a dead son. She is scornful of all pretention, alternately hard-headed and romantically yearning. Left alone all day by ‘Poldy’, she is lonely, possessive of him and mourns the splintering of their marriage by the death of Rudy, eleven years before this day who she recalls burying “in his little wooly jacket (642).”

Molly Bloom lives in the tangible, material world. There is no abstraction in her. Her memories are filled with names and physical descriptions, accounts of the wind and sea and everywhere the beauty of the natural world and flowers: “I love flowers Id love to have the whole place swimming in roses God of heaven theres nothing like nature the wild mountains then the sea and the waves rushing then the beautiful country with the fields of oats and wheat and all … the fine cattle going about that would do your heart good to see rivers and lakes and flowers all sorts of shapes and smells and colours springing up even out of the ditches primroses and violets (642-643).”

The novel ends with Molly’s understanding of Bloom’s gift, the reason she fell in love with him and stayed with him: “I liked him because I saw he understood or felt what a woman is (643).” She remembers his proposal of marriage. In doing so, she falls into a reverie of her youth in Gibraltar that unfolds into a kind of love song about the small scenes of life that make it worth living: “O the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire and the glorious sunsets and the fig trees in the Alameda gardens yes and all the queer little streets and the pink and blue and yellow houses and the rosegardens and jessamine and geraniums and cactuses and Gibraltar as a girl where I was a flower of the mountain (643).” That love song unwinds into her final memory and Joyce’s final word. She leaves all thought of her lover, Blazes Boylan, behind. She thinks of Bloom, stretched out beside her, his feet at her head, and she finally slips away into sleep dreaming of her answer to his proposal — “yes”, she say’s, a word she uses 9 times in 5 lines, “yes I said yes I will Yes (644).”

I know of no book that is a better fit for this spring’s arrival — its affirmation of all that is sweet in life is Joyce’s musical gift to us.

#I like listening to how the actress performs this; her pauses provide clarity and are necessary for that purpose. However, I think the experience of reading Molly’s soliloquy gives a better idea of what Joyce was after in terms of the seamlessness of her flow of thoughts and feelings.