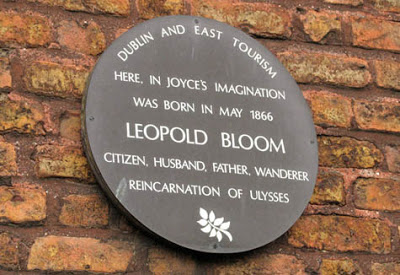

In Ulysses##, we meet a character who embodies multitudes. On June 16, 1904, Leopold Bloom, a Jew in Catholic Dublin and thus an outsider by birth, disaffected from his wife and still mourning the death of his infant son years before and thus exiled from his home, wanders the city selling ads for a newspaper, buying soap, spying on others, and following and rescuing Stephen Dedalus, a lost son himself. Over 20 hours pass during this day, and in that time Joyce shows us how Bloom, an ordinary, good man, carries within himself a continually unknotting universe of sensations and thoughts of every kind. His normality is crucial and ironic for Joyce means to show us that he is neither ordinary or normal, and could not be so. His human consciousness ensures his extraordinary nature for it guarantees him endless stories and shadings of emotion. He and his wife Molly, an everyman and everywoman, make us believe that each person we see, no matter where we go, bears within him or her self the same infinitely complex, capacious set of stories. Ulysses, in the persons of Bloom and Molly, assures us of the irreplaceable and dazzling nature of every mortal life.#

In Ulysses##, we meet a character who embodies multitudes. On June 16, 1904, Leopold Bloom, a Jew in Catholic Dublin and thus an outsider by birth, disaffected from his wife and still mourning the death of his infant son years before and thus exiled from his home, wanders the city selling ads for a newspaper, buying soap, spying on others, and following and rescuing Stephen Dedalus, a lost son himself. Over 20 hours pass during this day, and in that time Joyce shows us how Bloom, an ordinary, good man, carries within himself a continually unknotting universe of sensations and thoughts of every kind. His normality is crucial and ironic for Joyce means to show us that he is neither ordinary or normal, and could not be so. His human consciousness ensures his extraordinary nature for it guarantees him endless stories and shadings of emotion. He and his wife Molly, an everyman and everywoman, make us believe that each person we see, no matter where we go, bears within him or her self the same infinitely complex, capacious set of stories. Ulysses, in the persons of Bloom and Molly, assures us of the irreplaceable and dazzling nature of every mortal life.#

With the exception of glorious Molly Bloom’s final chapter, 36 hypnotic pages detailing her interior monologue as she tries to fall asleep on the night of the 16th, the best part of the book is Leopold Bloom’s meditations on his journey. He is a “decent, quiet man (146),” a man of “meek smiles (97),” a lost father who misses his dead son: “He would be eleven now if he had lived (54).” He does not have one good friend. Some of his acquaintances think him to be “a safe man (146)”, careful with drink, but also “that “he’s been known to put his hand down too to help a fellow (146),” as he does when he guides a blind man across a busy street, sensitive to “the blind stripling’s” feelings of worth: “He touched the thin elbow gently: then took the limp seeing hand to guide it forward. Say something to him. Better not do the condescending. They mistrust what you tell them. Pass a common remark (148).”

This encounter with the blind man provokes an empathetic reconstruction by Bloom of what such a life must entail and that leads to an expression of pity for the victims of a maritime disaster in New York City: “What dreams would he have, not seeing? Life a dream for him. Where is the justice being born that way? All those women and children excusion beanfest burned and drowned in New York. Holocaust (149).” Through the vehicle of his sympathetic imagination, he extends himself toward others.

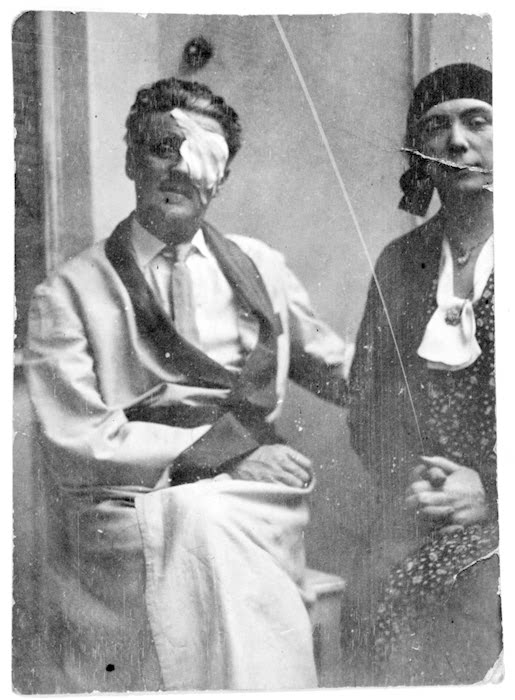

A hand drawing of Bloom by Joyce.

In Bloom, Joyce captures our wisps and breezy shifts of thought as if they were types of winds rather than logical, declarative sentences — a worry about money or a slip of thought about his dead son gives over to a sexual longing and act in the space of a heartbeat – as if a dry Harmattan blowing off the Sahara mingled and dissolved into a moist Levanter coming east off the Mediterranean. Like us, Bloom often feels before he analyzes, or his feelings and thoughts occur simultaneously. Joyce has both found a way to show us the rush of consciousness and has solved the aesthetic problem of how to describe that tangle to us in language that is both clear and literally transporting — “moving through the air high spars of a threemaster, her sails brailed up to the crosstrees, homing, upstream, silently moving, a silent ship (42);” in his descriptions of the shipping of oranges from “quayside at Jaffa (49);” in his imagined stroll through a Middle Eastern city ending with “Night, sky moon, violet, colour of Molly’s new garters. Strings. Listen. A girl playing one of those instruments what do you call them dulcimers. I pass (47).”

Joyce understands that within our imaginations, both awake and asleep, we have no boundaries and very little shame. Anything might slide into our awareness. He knows that we all keep our secrets. Bloom in a carriage on his way to a funeral: “Chinese cemeteries with giant poppies growing produce the best opium Mastiansky told me….It’s the blood sinking in the earth gives new life. Same idea those jews they said killed the christian boy. Every man his price. Well preserved fat corpse, gentleman, epicure, invaluable for fruit garden. A bargain. By carcass of William Wilkinson, auditor and accountant, lately deceased, three pounds thirteen and six. With thanks (89).”

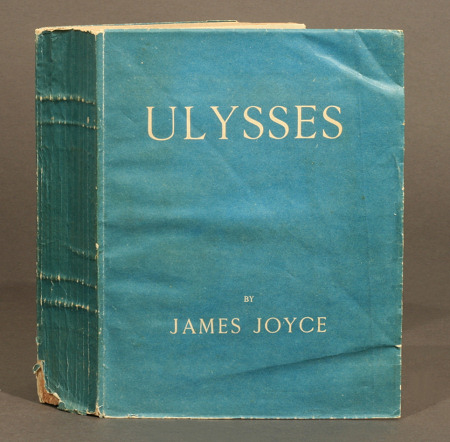

The first edition, published in Paris in 1922, in the blue cover Joyce insisted upon, it being the blue of the Aegean Sea, of Homer’s sea.

Bloom imagining a bath: “he foresaw his pale body reclined in it at full, naked, in a womb of warmth, oiled by scented melting soap, softly laved. He saw his trunk and limbs riprippled over and sustained, buoyed lightly upward, lemonyellow: his navel, bud of flesh: and saw the dark tangled curls of his bush floating, floating hair of the stream around the limp father of thousands, a languid floating father (71).” Within Joyce’s fluid visions, combinations of meanings and allusions merge, the conscious with the barely conscious, the unconscious coming to light and acquiring meaning, the religious connecting to the sensual and the mythic and the comic simultaneously.

Bloom responds to everything that crosses his perceptions or comes to his mind. Though many slip away, each moment in its inception becomes substantial and real and thus acquires authority and authenticity. Joyce is not after the construction of a plot in showing all this but the creation of a weighty feel of life. He briefly takes in “a onelegged sailor crutching himself … [growling] unamiably …(185).” As we might in an easy few seconds, he follows “a skiff, a crumpled throwaway … [ride] lightly down the Liffey, under Loopline bridge, shooting the rapids where water chafed around the bridgepiers, sailing eastward past hulls and anchorchains, between the Customhouse old dock and George’s quay (186-187).”And again, later, catching the pattern of the same “throwaway” on the river once more, a completely inconsequential item: “North wall and sir John Robertson’s quay. With hulls and anchorchains, sailing westward, sailed by a skiff, a crumpled throwaway, rocked on the ferrywash….(197).” Joyce knows how we see patterns everywhere and that those patterns are the foundations of our tangible sense of the world.

Joyce and his wife, Nora, after one of his many eye surgeries.

Joyce and his wife, Nora, after one of his many eye surgeries.

Bloom shows himself to be clever, physically courageous and someone who possesses deep, innate decency. He argues with a hateful anti-Semitic ‘citizen’ in a pub, a man who abuses him as a Jew and who uses the Irish Nationalist rhetoric of violence. Bloom makes his case: “But it’s no use, says he. Force, hatred, history, all that. That’s not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it’s the very opposite of that that is really life. … Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred (273).”

Stephen Dedalus, the artist awaiting his birth, and along with Bloom, Joyce’s avatar in the novel, is in trouble, and at risk to himself, Bloom rescues him. Having broken his glasses the day before and consumed by guilt for his insensitivity towards his mother on her deathbed, heavy with drink, he stumbles through Nighttown, Dublin’s red-light district and eventually is set upon by a prostitute and beaten by a drunken soldier. Bloom pays off the prostitute, confronts the soldier, and in providing Stephen a sanctuary, takes him back home with him, a substitute for Rudy, his lost, beloved son. Bloom ends his wanderings and brings us back to sleepless Molly and her great monologue to end the book.

This exhortation appears at least twice, thought once each by Bloom and Dedalus: “One life is all. One body. Do. But do (230).” It is a word play on the sacrament of Catholic Commumion, on the transmigration of souls, and I am sure possesses a further significance that I am missing, and I love it for it drives home this awareness — in the person of Leopold Bloom, Joyce reminds us of the transitory nature and transcendent wonder of being alive in our one, rare body and span of time. Given the chance, Bloom can awaken us and give the summons to set off on our own journeys.

##Ulysses is 644 pages long, and it reads longer than its page length. Joyce challenges the reader on every one of those pages. The experience of reading it is all encompassing, as if one had stepped into a small room and then had it sealed behind one, and a parade of lives and vignettes and voices and images of every realistic and hallucinatory kind began to be displayed on the walls and ceiling. This experience goes on and on for as long as you read. You are immersed within Dublin on that June day and within the emotions and minds of three characters especially, the Blooms and Dedalus. In a letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, one of several wealthy patrons, he describes the experience of writing Ulysses: “The task I set myself technically in writing a book from eighteen different points of view [18 chapters in the novel] and in as many styles, all apparently unknown or undiscovered by my fellow tradesman, that and the nature of the legend chosen [Homer’s Odyssey] would be enough to upset anyone’s mental balance.”

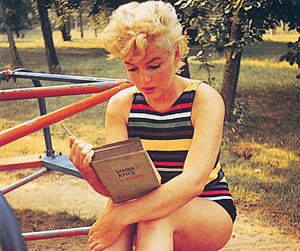

Sometimes the writing becomes tedious and pummeling — Joyce’s inventiveness goes on and on and on. Pages could have been cut, sections trimmed. However, with the exception of War and Peace, I do not think I have ever read another novel that is more thrilling and more complete in its treatment of the human condition. And it has a happy ending, a comic ending, a wonderful promise of reconciliation. Please, give it a shot. Marilyn did.

Sometimes the writing becomes tedious and pummeling — Joyce’s inventiveness goes on and on and on. Pages could have been cut, sections trimmed. However, with the exception of War and Peace, I do not think I have ever read another novel that is more thrilling and more complete in its treatment of the human condition. And it has a happy ending, a comic ending, a wonderful promise of reconciliation. Please, give it a shot. Marilyn did.

Watch what Mr. Fry says — a perfect two minute summation.

#Humans of New York has the same vibe — a sublime respect for the individual’s wealth of experience. We gain an intimation of the immensity of the life that lies within them based on their answers to the host’s questions. Each one is a Leopold Bloom or Stephen Dedalus or Molly Bloom.

*Joyce worked on Ulysses for 8 years and once published had to fight pirated editions and censorship. After leaving Dublin, he could never settle. Nothing mattered to him except his writing and his family, but his ambition was enormous. He wanted to write the greatest modern novel, one which no other novel could ever compete with in depth of emotion, complexity, modern style, and scholarship. “He died … in Zurich, of a perforated ulcer, on January 13, 1941. He was fifty-eight, and a very old man. He had burned the candle all the way down. He had spent eight years on “Ulysses,” and fifteen years on “Finnegans Wake,” which was published in 1939. ‘“My eyes are tired,”’ he wrote in a letter to Giorgio [his son], in 1935.” From “Silence, Exile, Punning” by Louis Menand, a terrific sketch of Joyce’s life. From that essay: “If ‘Ulysses‘ isn’t fit to read,” he [Joyce] once said, “life isn’t fit to live.” Amen.

I have not read Ulysses’. I will now!

I’ve read Ulysses twice, and Finnegan’s Wake once. I felt those books were more creative than his short stories, because in the short stories, the man would drunk and come home and beat up his wife, and then that would be repeated story after story. By writing the two novels, he broke away from one story, and tried to show life. Reading it a second time, and years between the readings, I noticed something different than the first time reading. I enjoyed the books.