Prologue:

My mother phoned me at college. My father’s best friend, a State Police officer, had been killed while directing traffic at the Reading Air Show. A bus had struck him head on. That evening I called him, expecting to hear a vibration in his voice, the aftereffects of the shock, but he was calm; his concern was for me. I think he was trying to reassure me about my worry over his state. He said, “You get used to these things.”

Cold facts alone can warn us that a grim backstory exists just under their surface. The 1930 census for Philadelphia lists my father’s home address as being 705 Edgemore Road: Dad’s home in 1930: he was 16. Eight people lived there. My paternal grandmother, Jane, 39, my father’s brothers, James and Fred at 14 and 10 respectively, their sisters, Marie, 18, Catherine, 13, Joan, 4 and Jane, 2. My father was 16. Next to his name a job is posted – a photographer’s apprentice. They did not own their residence. They were renting. My grandmother’s marital status is listed as single.

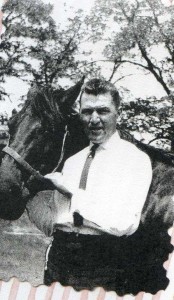

Some of this story has been lost to time and to the dead, but we think we know this much – her husband, my paternal grandfather, a physically imposing man, a lover of horses, a baseball player, Charles Frederick Wall, was also a plumber.

He was removing a cast iron tub in the course of a job. Something happened. Someone slipped, a knot came undone in a rope, the weight was too much, the moment in all its sudden fury is lost, but the tub came loose and crushed his legs. Both legs had to be amputated in what may have been a desperate attempt to stop infection, perhaps gangrene, from moving inexorably toward his heart — the first antibiotic was not available in the United States until 1932. My paternal grandfather died on December 12, 1928 of blood poisoning. The medical term for blood poisoning is septicemia. In the 1930’s sepsis was the number one cause of early death in the United States.

He was removing a cast iron tub in the course of a job. Something happened. Someone slipped, a knot came undone in a rope, the weight was too much, the moment in all its sudden fury is lost, but the tub came loose and crushed his legs. Both legs had to be amputated in what may have been a desperate attempt to stop infection, perhaps gangrene, from moving inexorably toward his heart — the first antibiotic was not available in the United States until 1932. My paternal grandfather died on December 12, 1928 of blood poisoning. The medical term for blood poisoning is septicemia. In the 1930’s sepsis was the number one cause of early death in the United States.

I try to imagine what may have occurred. How would the news have come to my grandmother? Few families had phones in their homes. From a phone message delivered to a corner grocery store or saloon and then delivered by an out of breath boy to her. From a police officer? From a helper who had been present and who did not want to deliver the news to my grandmother, who might have stood before him, reading his face, numb, perhaps with one of the little girls hoisted in one arm. My grandfather probably would not have had a private room. The family would not have been able to afford one. He would have been placed in a ward. No, wait… crushed legs? … he probably went into surgery immediately. Maybe they amputated immediately. One shock would have followed another. All of it would have felt overwhelming.

I have to believe that my grandmother would have taken her oldest son to see his father, and that my father would have insisted that he go. He would have seen this: my grandfather would have looked very sick – his face would have been very pale and his breathing would have been labored. My 14 year old father would have watched him shivering, but he would have been warm to the touch, often sweating. He might have been able to see his heart beating rapidly under the sheets. The bacteria in his blood would have increased despite his immune system throwing everything at it. Blood clots may have formed. Eventually, he would have seen his grandfather rendered unconscious, perhaps comatose. It might have taken him several days to die.

Who was with him when he died? Did the family conduct the wake in their home, my grandfather perhaps packed in ice in a coffin resting on sawhorses in the sitting room? I have to believe that my father would have been a pallbearer — a boy in a dark suit hoping that his hands would not slip on the handles of his father’s coffin. My father, the oldest son, would have been expected to carry himself as a man of the time – stoically, greeting his father’s friends and co-workers, the parish priest, the neighbors. Again and again at the wake men with beer on their breath would have leaned in close and told him that he was now the man of the house and that he had to take care of his mother. “You get used to these things.”

Look at that date — thirteen days before Christmas, a ghastly Christmas. My father is in ninth grade. In 10 months comes the Crash of ’29 and the Depression. In a matter of days, my grandmother has become a widow with seven children, two of whom are infants; the only “safety net” is family, the Church, neighbors; maybe a few dollars comes from a ward leader. She would have been terrified. My father would have been acutely aware of her fear. He dropped out of school, a fact he tried to hide for the rest of his life. He never went back. Out of seven children, only Joan and Jane graduated from high school.

I believe that my grandfather’s death was the central fact of my father’s early life, and that it set him on a way of behaving that he held to until his own death. He never spoke of his grandfather’s death in any detail, or of how hard the next 5 or 6 years must have been. Instead he seemed to adopt this ethos — put it behind you. Go on. Do not look back. Do not talk about tragedies or hard times. Show your children a strong man whose love was best expressed through the table full of food, through a living room piled high with Christmas presents, through the ten dollar bill slipped into our hands quietly, through the physical labor he afforded in refinishing pieces of furniture, in helping us move, in playing with his grandchildren. A superb storyteller, he also wore another persona, one that took on a quiet, benign presence at crowded tables and rooms thick with talk and laughter. Against the odds, he had survived, and he owned a home, he had married happily, and he had fine children and grandchildren. Against the odds, he had provided. What else was there to say?

From 14 to 23 he remained in Philadelphia, growing up without a father, always hustling, working as a caddy, doing other jobs that have been lost to our knowledge, working to stay a step ahead of the inhuman effects of the Depression. My brother remembers driving in Philadelphia with my father as a boy on a tour of his various homes – there were at least four. We are certain of only two locations, but we do know that his mother lost one home because she could not pay the bills. She took in sewing and perhaps others’ laundry to try to keep her family whole. She kept the paychecks of my father’s sister, Catherine. She must have taken my father’s as well, or at least a portion of them.

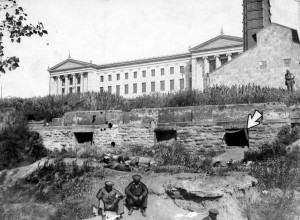

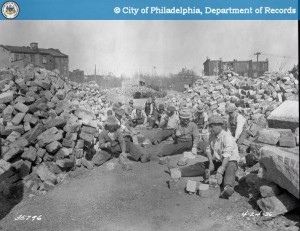

Coffee and sandwich line on Cherry Street, 1932 and Homeless men living in dugouts under the Art Museum, 1932

Coffee and sandwich line on Cherry Street, 1932 and Homeless men living in dugouts under the Art Museum, 1932

All Philadelphia suffered. In November of 1930 the Committee on Unemployment Relief had $3.8 million dollars on hand to aid unemployed families. They ran homeless shelters for 12,000 of the dispossessed. The need was so great that in less than a year, all the money had been spent and they had to close down. The Community Chest Campaign spent $10 million in less than a year on soup kitchens, breadlines and shelters. Nineteen thousand mortgages were foreclosed in 1932 alone. Hospitals were reporting cases of starvation. The unemployment rate peaked at 25% in 1933. Eventually the WPA employed 47,000 Philadelphians on various projects. My father would have lived in the teeth of those gales. “You get used to these things.”

All Philadelphia suffered. In November of 1930 the Committee on Unemployment Relief had $3.8 million dollars on hand to aid unemployed families. They ran homeless shelters for 12,000 of the dispossessed. The need was so great that in less than a year, all the money had been spent and they had to close down. The Community Chest Campaign spent $10 million in less than a year on soup kitchens, breadlines and shelters. Nineteen thousand mortgages were foreclosed in 1932 alone. Hospitals were reporting cases of starvation. The unemployment rate peaked at 25% in 1933. Eventually the WPA employed 47,000 Philadelphians on various projects. My father would have lived in the teeth of those gales. “You get used to these things.”

Men cutting granite block at 23rd and Callowhill, 1933

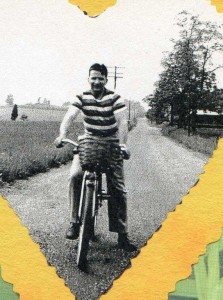

But he was also growing up without the restraining influence of a father. He would have possessed the optimism that comes to a man filled with youth and strength. He stood 5’10” tall and had enormous hands, the hands of a prizefighter, big arms and a big chest. He earned enough to buy suits. In some photographs he looks like a longshoreman who decided to dress like a dude. You don’t dress like this unless you are feeling your manhood in powerful ways.

But he was also growing up without the restraining influence of a father. He would have possessed the optimism that comes to a man filled with youth and strength. He stood 5’10” tall and had enormous hands, the hands of a prizefighter, big arms and a big chest. He earned enough to buy suits. In some photographs he looks like a longshoreman who decided to dress like a dude. You don’t dress like this unless you are feeling your manhood in powerful ways.

In the second photo, he is a few years older. Cut from the photo is whose waist his arm is circling — not our mother’s. I think my old man was a hound.

In the second photo, he is a few years older. Cut from the photo is whose waist his arm is circling — not our mother’s. I think my old man was a hound.

Everybody he would have known would have been struggling and thus perhaps his burdens would have been lessened. He was young and strong and city life would have been exciting.

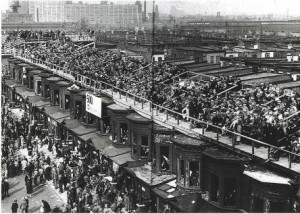

The rooftop stands across from Shibe park (Connie Mack Stadium): the 1930 World Series

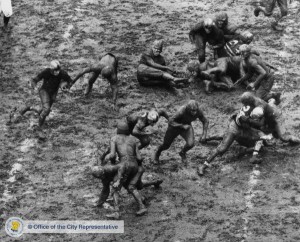

The Army-Navy game of 1934 played at Franklin Field

The Army-Navy game of 1934 played at Franklin Field

We cannot see the arc of a life until it is over or in its last years. We think of lives as a narrative, as a story with multiple climaxes and revelations, with tragedies and romances and the sure refinement of character over time. When the arc passes its zenith, those story lines begin to clarify. If we are fortunate, looking back, we can see the events and people who relieved us of our aimlessness. My father had reached his young manhood and at 23 was about to discover one of the twin salvations of his life.