It started with The Book; at least 70 years old, leather brown, cracked and dry, it measures 14″ long and 12” wide. Its pages bulge and leaf out at the ends. Brittle, a faded, dusty color, they break to the touch. Small pieces litter the table where I work. It overflows with post cards, announcements, poems, and an unknown number of newspaper clippings that record an earlier era in my father’s career as a Pennsylvania State Police Officer. I think that my mother began to keep it, but I am not certain for some of the clippings predate their meeting. Maybe his mother began it. My mother no longer remembers. I cannot imagine that anyone else but them would have been so loving and proud and dutiful.

I am after something to see. What the eye sees is intimately connected to what the mind might think or imagine. Thus, if I can bring back to my life what my father might have seen, maybe in some obscure way that I cannot quite explain, maybe our minds can meet, maybe I can slip into the past, Philadelphia’s past, his past. Maybe I can understand something about his life as he lived it long before I arrived.

I am after something to see. What the eye sees is intimately connected to what the mind might think or imagine. Thus, if I can bring back to my life what my father might have seen, maybe in some obscure way that I cannot quite explain, maybe our minds can meet, maybe I can slip into the past, Philadelphia’s past, his past. Maybe I can understand something about his life as he lived it long before I arrived.

The Book contains what might be the most intimately factual remains of my father’s life, and thus, for my search, I will mine it as best I can for insights and answers, and use it as an engine to provoke further questions.

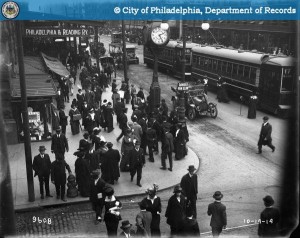

12th and Market in 1914, the year of my father’s birth. This is the world he entered, a cityscape of trollies, Model T’s, men in suits and hats, women in Edwardian formal wear, a world on the brink of modernity.

12th and Market in 1914, the year of my father’s birth. This is the world he entered, a cityscape of trollies, Model T’s, men in suits and hats, women in Edwardian formal wear, a world on the brink of modernity.

The Book opens to a grayish document with an ivy border: This Testimonial Is Awarded To … and what follows, written in a beautifully cursive hand, Master Charles Joseph Wall For having completed in a satisfactory manner, the Grammar Course of Study at … and again in that elegant, flowing hand, a nun’s hand, perhaps the Mother Superior’s … St. Callistus’s School, June, 1928, signed by Danial S. Cronahaus, Rector. My father was 14.

St. Callistus was founded in 1920, another parish for the increasing number of Catholics, immigrants and the children of immigrants in what was becoming the city with the largest population of Catholic school children in the nation. He walked the 1 and ½ blocks from this home on Leeds Street: 6610 Leeds Street: Dad’s Home in 1920; he was 6 years old –the porch on the right with the cheap, covered rocking bench.

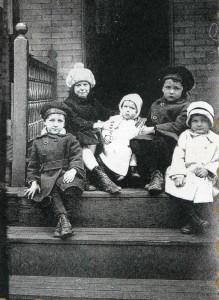

I believe this photo was taken at Leeds Street. My father is seated on the top step at our right in a winter cap, some kind of sailer’s cap. He looks forlorn. He and his brothers and sisters are dressed warmly; these aren’t ragamuffins or street kids or children on the edge of poverty. Five of what became seven children are pictured here.

I believe this photo was taken at Leeds Street. My father is seated on the top step at our right in a winter cap, some kind of sailer’s cap. He looks forlorn. He and his brothers and sisters are dressed warmly; these aren’t ragamuffins or street kids or children on the edge of poverty. Five of what became seven children are pictured here.

My father saw this older building every school day until June of 1928: St Callistus: Dad’s Grammar School. He would have walked up and down those steps.

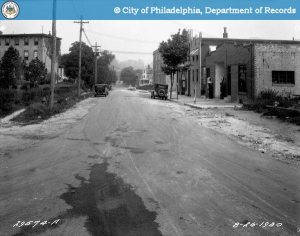

Plate #3 of the Aerial Survey of Philadelphia taken in 1930 shows my father’s neighborhoods. There is more green space, more openness than I had imagined.

One Block from St. Callistus, 1930

This photo also seems to support the sense of a larger sky, trees, a less dense neighborhood than one imagines for Philadelphia. He would have been able to have walked to undeveloped areas and played there. It remonds me of West Lawn, the Reading suburb where we moved when I was 9 — an early 20th century development of twin houses with big porches and tree shaded streets. We moved there from Myerstown and a big house with fields in back and woods across the street. We rented in Myerstown. Why there and not in Labanon or in Reading? He never spoke about his love of the outdoors. Like most men of his generation, he was silent about such feelings, but he delighted in being outside shoveling snow, mowing, helping my brother-in-law build his home, walking in the woods with his grandchildren — moving, always moving in the open. In this love one fragment of his soul may be illuminated.

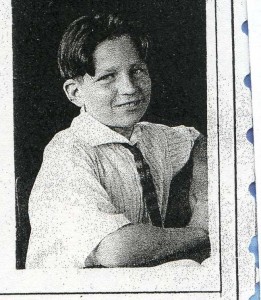

Here he is, smiling, maybe 8 or 9, his thick hair defining his head and face as it did all his life. He looks happy, at ease, the bulk of his large chest and big shoulders beginning to show themselves.

He survived childhood in an era before antibiotics. He survived the heat wave of August, 1918. On the 7th, 5 people died in Philadelphia from a record day of 105 degrees. For close to a week, all over the city, workers were overcome by the heat. Leed Street would have been filled after sundown — children released into the shadows to play, people preparing to sleep on their porches, drinking beer on their stoops, out from under their stifling roofs. He survived the terrible outbreak of the Spanish Flu in mid-September of that year. He would not have understood the fear, but he would have been aware at 4 1/2 year’s old that something was wrong. A doctor’s car was blockaded by parents in Manayunk; he was not allowed to leave until he had treated their children, 57 in all. Churches, schools, bars and theaters closed. His sister Marie, two years older, would have been home from school. He would have seen people, maybe even his own father and mother wearing gauze influenza masks. By mid-October when it burned itself out, Philadelphia had suffered 12,000 deaths and almost 50,000 who had become ill, the highest toll of any American city. He would have been aware that familiar people in his own neighborhood had disappeared, perhaps other children his age, his playmates.

He survived all this, he dodged all these blows, and in June of 1928, would have graduated from 8th grade, Master Charles Joseph Wall, almost certainly beaming under the eyes of his father and mother and the nuns and priests, and thankfully, without any knowledge of what was to come down upon him in just 7 months, and also upon his mother and brothers and sisters like a Dickensian curse on a childhood.