All that we are is the result of what we have thought. Buddha

The shoes resting on the cellar steps – that image stays with me — two by two, each on a succeeding step. Every Sunday night while his children attended grammar or high school, he would sit by his workbench in the cellar, open his wooden, green shoe-shine box, arrange the polishes and cloths and brushes and shine all our school shoes for the week. We picked them up off the stairs and in the morning set off “looking sharp” as he said.

The shoes resting on the cellar steps – that image stays with me — two by two, each on a succeeding step. Every Sunday night while his children attended grammar or high school, he would sit by his workbench in the cellar, open his wooden, green shoe-shine box, arrange the polishes and cloths and brushes and shine all our school shoes for the week. We picked them up off the stairs and in the morning set off “looking sharp” as he said.

His sets of chores matched the season: painting in the spring and summer, leaves and garden cuttings to pick up in the fall, mowing the grass, snow in the winter, oil changes and clean ups as necessary, set the awnings over the front porch in May, take them down in October, and so on in every month. Until age took his legs, he seemed a man in perpetual motion.

His chores were more than necessary household tasks to be disposed of as quickly as possible. He invested himself in them. He tried to do them “the right way” each time. Charlie Wall was the son of hard-driving Irish parents and a good, old school Catholic and thus as far from a practitioner of Zen Buddhism as is possible, but Zen helps to explain how he did things. To oversimplify the definition, the practice of Zen is a search for a way to live each day that produces harmony; one way someone might access that harmony is through a patient focus on each task; each task becomes the center of the moment. It is about “doing one thing at a time, and about ‘noticing’ one thing at a time. Focus is a state of awareness that goes beyond just actions – it is the place of calm mental presence in this moment.” * His imperturbable calm, his quiet force – two of his most memorable qualities.

As a callow young man, I became frustrated when I worked with him. Whatever it was, I wanted to get the job finished. I was moving at 1000 miles per hour and always had 10 other things I would rather be doing. I thought he moved … so … slowly, but he wasn’t moving slowly; he was acting deliberately and within a pattern of thought and prior behavior. For example, when he refinished furniture, he stripped the pieces of their previous layers of varnish or paint and took them down to bare wood. I watched him work through various steps of this process and his sanding of the surfaces and nooks and hard-to-get-to places told the tale of his method. He used the right tools and patiently collected all of them before he started. He reached out for medium sand paper and it was at his hand. He reached for a thin scraper and it was right there. He did not hurry. He did not work at a task so much as enter the task.

Maybe that is one reason that he loved golf. He was good. I know just enough about the game to recognize a smooth, graceful swing; he looked all of one motion when he teed off, effortless and efficient. Golf requires the ability to block all distractions, to reproduce the same habitual movements as required by the shot, by the putt, the chip, the drive. It is a game of solitary effort even in a group of other players, and though he loved to be with his Statie friends when he played, laughing and telling stories, with golf he had moments with every hole when he had to let them go and bend over the ball and concentrate on that separation and on his solitary mastering of a difficult skill. He could do it.

Maybe that is one reason that he loved golf. He was good. I know just enough about the game to recognize a smooth, graceful swing; he looked all of one motion when he teed off, effortless and efficient. Golf requires the ability to block all distractions, to reproduce the same habitual movements as required by the shot, by the putt, the chip, the drive. It is a game of solitary effort even in a group of other players, and though he loved to be with his Statie friends when he played, laughing and telling stories, with golf he had moments with every hole when he had to let them go and bend over the ball and concentrate on that separation and on his solitary mastering of a difficult skill. He could do it.

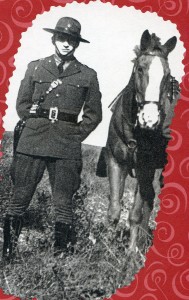

I think I have been pursuing him for decades. My father’s appointment letter to the April 4, 1938 class of the “Pennsylvania Motor Police Force” was sent out by Commissioner Foote on January 12, 1938, my father’s 24th birthday. In October of 1982, about two weeks after my 30th birthday, I made a phone call to a Pennsylvania State Police information officer and asked about applying to join the Force.

I was not bored with teaching; after seven years I was just beginning to grow comfortable in my classroom persona and confident about my skills. I loved my job, but I also felt the tug to follow my father, to attend the Academy, to wear the stripes. Maybe I even hoped that someday I too might be Sgt. Wall. What scenes of joy I imagined. I was seeking his approval. I’m not sure I understood that at the time, but I know it now; I wanted him to sit in the audience in Hershey and see me on stage in the uniform and feel pride surge within him.

The Information officer was kind. She told me that the cut-off date for application was 30. No exceptions. I told him about my call. He was surprised. Very little surprised him. I think he was pleased that I had tried. He only smiled. That is all I remember.

What if I had called six months before turning 30? I think I would have gone through with it. The power to be found in continuity and the temptation to become some part of what he had done would have been overwhelming. I probably would have chosen another life with all the never-to-be-known dynamics of such a choice. That is how strong his gravitational field has been for me.

In writing about him I’ve sometimes felt myself to be the ghost and of him as real. Invisible, I’ve been looking at him, following him through decade after decade, watching him work, trying to see how he found joy and endured sorrows. I’ve tried to see him as both a son and a stranger, no not a stranger, that’s not accurate, but maybe as an outsider who looks at another and asks, “Who was this man?”

After death our loved ones exist only in memory, and then it is too late to ask new questions. Recently I read that ‘“Theodor Adorno, the German sociologist, remarked that memory is the only help left to the dead. “They pass away into it,”’ he wrote”; … he is … someone whose life [we] must save, without knowing whether the effort will succeed.”’ ** Memory does revive events and images. I have discovered sides to my parents I had never known, but I am still chasing mysteries, especially the central one – what were they at the core?

Maybe his mystery comes down to this: he understood that life can be cruel — fathers die young, the safe world blows up, and as a 15 year old he had to scramble just to put food on the table and help keep a roof over his family’s head. Later, he was forced to confront this terrible fact — children can die before their parents.

He had the Church, his wife and children, a sheltered place where the ever present milk bottle on the dinner table came to symbolize his ability to provide. He could drink a beer at night, watch Archie Bunker, play golf, add improvements every year to his home, walk with his grandchildren. He had the State Police, his own kind of priesthood. That is not an exaggeration. He never would have said so, but all his life he acted as if he were part of a sacred and select circle of comrades with whom he kept the oath to uphold the law, protect the innocent and keep order. He understood that there were bad men in a hard world who meant to do good people harm. He chose to put his body on the line to stop them.

He had the Church, his wife and children, a sheltered place where the ever present milk bottle on the dinner table came to symbolize his ability to provide. He could drink a beer at night, watch Archie Bunker, play golf, add improvements every year to his home, walk with his grandchildren. He had the State Police, his own kind of priesthood. That is not an exaggeration. He never would have said so, but all his life he acted as if he were part of a sacred and select circle of comrades with whom he kept the oath to uphold the law, protect the innocent and keep order. He understood that there were bad men in a hard world who meant to do good people harm. He chose to put his body on the line to stop them.

In his 80’s my youngest sister asked him and kept after him to recite the State Police Oath, one he had memorized almost 60 years before. He grumbled and then he recited it, word for word. A good priest does not forget the Word.

This remains. As mother and father, Christine and Charlie left us alone to work out our own lives — the product of two imperious mothers, they chose not to be. They did not neglect us. We had rules: go to Mass, don’t make a scene, work hard, be polite, respect others. My father told me once to “never come home in the back of a police car.” None of us ever did.

They wanted us to find our way to good lives, whatever shape that looked like. We had the freedom to make our own mistakes. My brother and two sisters, all four of us, became independent, strong individuals. I don’t know that we have much of their grace and elegance, but we have stuck together, and we have tried our best to honor them with the content of our own lives.

Christine and Charlie gave us life and opportunities and many of their talents. They loved us. They wanted the old immigrant dreams for us, that we would be successful and live with decency and remember family.

There are now five grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. All of them carry Christine and Charlie in their genes, and now a portion of their stories has been set down in these 13 essays. I hope their stories carry their trials and strengths into the lives of those great grandchildren and their children for many more years. Our mother and father are and have been well loved. I hope that they are remembered.

There are now five grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. All of them carry Christine and Charlie in their genes, and now a portion of their stories has been set down in these 13 essays. I hope their stories carry their trials and strengths into the lives of those great grandchildren and their children for many more years. Our mother and father are and have been well loved. I hope that they are remembered.

* http://www.thechangeblog.com/zen-and-the-art-of-focus/

** The New York Times: March 26, 2012: The Titanic And The End Of An Era: Roger Cohen