For almost a year, once a week in the early morning, I have driven south of Coatesville, rising from the old steel plants through a sharp cut into farmland. Outside of town the two lane road loses its sidewalks and shoulders. No one slows down. Most cars pick up speed. Each time I have made this trip I have seen the same man making his way along that stretch.

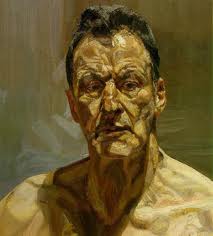

He walks as if his legs end in stumps in a blunt, heaving, da-Dum da-Dum rhythm. He has a broad Irish face, a heavy chest and a blur of obscurely colored hair that alternately bristles and falls. He might be in his early seventies. I have never seen him wearing a coat. Drenching rain, snow squalls, bone-snapping cold with the wind scoring the air – he always appears, forward pitching, in a dark, short sleeved t-shirt and jeans.

He walks as if his legs end in stumps in a blunt, heaving, da-Dum da-Dum rhythm. He has a broad Irish face, a heavy chest and a blur of obscurely colored hair that alternately bristles and falls. He might be in his early seventies. I have never seen him wearing a coat. Drenching rain, snow squalls, bone-snapping cold with the wind scoring the air – he always appears, forward pitching, in a dark, short sleeved t-shirt and jeans.

a portrait by Lucien Freud

Once I saw him in Coatesville on the sidewalk moving west on Route 30, but he begins his journey somewhere in the open country south of town.

I don’t think I’m catching these glimpses of him on his only day for walking. I’d bet he completes this march most days, maybe every day.

I don’t have the novelist’s gift for imagining the frames of his life – mother, father, childhood, his ennobling and scarifying episodes. Instead I wonder about him. Where does he go? What history informs the daily, recurrent images of his progress? Does anyone wait for him to return and worry about the cars taking those narrow curves too fast? He looks as if he carried heavily muscled shoulders and arms in his youth – did he feel the need to be out and moving then? Why does he never wear a coat?

He causes me to think about those who watch us, who note our routines, who do not know us but whose eyes we have captured. What questions occur to them? I don’t conceive of this ‘looking’ in any sinister way. Our gaze is promiscuous. We cannot help ourselves. When we go out into the world, we automatically open our stumbling and gliding bodies and faces to others. Our interior lives are closed to them, but they see us and also think, “What goes on in their days?” Very few of us would stop the car, step out and say, “How are you? Do you need a ride?” I am too polite, shy, cautious, afraid of being misinterpreted, too busy, I guess as well, to do so. Would he just stare at me, on edge, feeling cornered perhaps? No, the whole scenario is wrong.

Maybe we gain some form of compensation from the mysteriousness of strangers wherever we encounter them long enough to ponder them. They cause us to wonder, to offer conjecture, to meditate. Their faces float out of crowds at airports or suddenly become individual in the flow of pedestrians as we sit at an outdoor café or in museums, or they materialize along treacherous roads where they move deliberately along lines of purpose we will never know.