It would not be polite to ask those older than me whether they too dream of the dead. Most of them, I suspect, are wary of any such experience and would see the question as intrusive, and of course, at a certain age, we all grow much closer to being the one dreamed of. That thought alone comes too close to the skin to be comfortable.

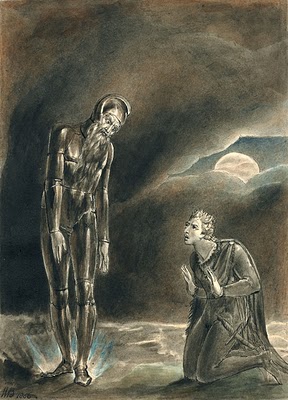

Hamlet and His Father’s Ghost by William Blake

Hamlet and His Father’s Ghost by William Blake

I know that my older sister dreams of my father and our aunts and even our lost brothers, but the word dream does not apply to some of what she sees while asleep. A number of her ‘dreams’ are closer to a trance, a state of mind where she knows that she is dreaming and the visiting figures deliver messages and have a startling sense of reality to them. I take these visions seriously. I’ve taught Hamlet too many times not to do so. The Ghost of Hamlet’s father is a presence so exact and demanding that the living can identify him by the color of his beard and the lines in his hands. After speaking to his father’s spirit, Hamlet tells Horatio that “There are more things in heaven and earth … than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”* I think of that hard won wisdom whenever I am tempted to discount the potential of worlds that lie outside my senses and of my empirical, logical awareness. Add this to the equation, raised a 1950’s Catholic: for us, a regiment of spirits filled the air — guardian angels accompanied us, and the saints helped us, Jude and Christopher and my namesake, Michael, and lurking in corners, suspended from ceilings like spiders, devils watched us and whispered to us. A lofty, adult skepticism does not beat back those images so easily.

Jamie Wyeth also dreams of the dead, and he has shown us his dream. Two of his most recent paintings show his father, Andrew, and his grandfather, N.C., both dressed in mariner’s foul weather gear, standing on a rock ledge on Monhegan Island and watching a turbulent ocean.** In his commentary on the  painting he spoke of it as a result of a particularly vivid dream. Images suggest narratives — before’s and after’s. Where did N.C and Andrew go to retreat from the storm? Why were they visiting? What did they say to each other? From where had they come? I know that there is an absurdity in that line of questioning – they are daubs of paint on a canvas, that’s all. A dream is an electrical and biochemical excitement of the brain, that’s all. Those are the conclusions of a pure rationalist, a believer in the laws that govern the solidity of the material world. Memory calls back the dead to us. We respond. Faces and figures revive emotions. That’s all. Yet even as I write these sentences, a fundamental part of me keeps shaking his head and thinking, No, there’s more.

painting he spoke of it as a result of a particularly vivid dream. Images suggest narratives — before’s and after’s. Where did N.C and Andrew go to retreat from the storm? Why were they visiting? What did they say to each other? From where had they come? I know that there is an absurdity in that line of questioning – they are daubs of paint on a canvas, that’s all. A dream is an electrical and biochemical excitement of the brain, that’s all. Those are the conclusions of a pure rationalist, a believer in the laws that govern the solidity of the material world. Memory calls back the dead to us. We respond. Faces and figures revive emotions. That’s all. Yet even as I write these sentences, a fundamental part of me keeps shaking his head and thinking, No, there’s more.

Visions, dreams, a rapture, or grandly so, an oracular phantom presence – call it by any similar name and it will carry an unspoken, irrational promise – there is a message from the other side in my image, in my words. Can you discern it? And so … to my dream.

I am riding in a car with my father. He is driving down an alley in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, my birth place. I don’t recognize any landmarks, but I know it is Lebanon. My perspective is split in two – I sit next to my father inside the car, and I hover above the car on my side. The Sun is shining. I have a vague impression of trees and phone and electrical wires. We are moving slowly. We pass an old garage, one built from stone or block with a roof pitched down on all four sides; a small dormer window at its peak faces the alley. The car stops. My father suddenly appears on top of the roof of the car. He is about my age now, early to mid-60’s. His wears his thick white hair in a long brush cut. On his left side he wears a revolver in a U.S. Cavalry holster, the holster worn backwards so that he would have to bring his right hand across his body to pull it out, the butt end resting just above his hip. Looking away from me, at the garage I think, he does this. He draws out a large revolver. He turns his head to me and says these words, the only words spoken in the dream: “You are in danger.” The dream ends. I might have awakened and fallen back to sleep.

On the surface of this dream a vigorous, very much alive father protects and warns his son, his occupation as a police officer and parent as deeply embedded in him as pieces of crystal in granite. That seems straightforward … except for the verb he used in the only sentence he spoke to me – “are”, the present tense … you are in danger now. I cannot think of an enemy who wishes me harm. I have noticed nothing out of the ordinary around me, my home, or the places I tutor. No shadows in the yard at night, no frenzied barking and bared teeth by the dogs, no peculiar phone calls, nothing that has sent cold ripples of alarm along my body. Nevertheless, that “are” troubles me, and has made me alert to any signs that might hint that ‘something wicked might come this way.’ That also feels foolish, as if I had suddenly embraced the idea of portents and omens circling my waking life like invisible birds. But perhaps not so foolish in this regard — the dead are always with us in the all powerful transmissions of our memories. In that realm they whisper to us, and sometimes we answer, and sometimes they summon us, probably lonely themselves, anxious to bridge the divide separating them from heartbeats and the faces of those they loved. If the dead do not dream, then they might only see us in our own dreams. In that wilderness perhaps they keep vigil, alert to danger, cavalry revolvers strapped to their sides.

*Hamlet (1.5.166-7)

**Andy Warhol, watching them, his back turned to us, appears in the second painting of this scene.

Good one! Great to see you yesterday. Hope you will show up to breakfast or lunch once in a while.

My mother died very young. I believe-no, I hope she’s in the proverbial better place, if for no other reason than to make up for her lack of time here. I hope she can see me–at my best, and my worst, so she can be proud of me, to know that I still need her guidance, and to know how much I miss her. Thanks Mike.