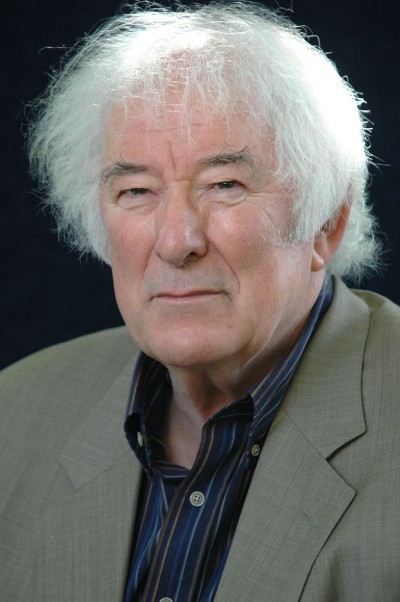

Seamus Heaney is dead. I carried Death of a Naturalist in my pack when we hitchhiked across Ireland in the hot summer of 1976. I was lucky enough to read his poems in his natural habitat — at night camped in a pasture outside Ballinasloe, the diamond stars scattered around the bowl of the sky; on Inisheer, my pack propped up by our tent, the sea blazing with sunlight a hundred yards away on the other side of stone walls and fields, and on July 4 on the freighter that took us into Galway, its hold full of red horses that the islanders had swum out hitched to their currachs; they strapped them into harnesses and hoisted them aboard; in Londonderry in the bus station across from the main British Army base where my friend and I watched a returning five man patrol running double time, their automatic weapons centering on us just for a moment when they came around the corner. Seamus Heaney is dead. This is a mournful day.

Seamus Heaney is dead. I carried Death of a Naturalist in my pack when we hitchhiked across Ireland in the hot summer of 1976. I was lucky enough to read his poems in his natural habitat — at night camped in a pasture outside Ballinasloe, the diamond stars scattered around the bowl of the sky; on Inisheer, my pack propped up by our tent, the sea blazing with sunlight a hundred yards away on the other side of stone walls and fields, and on July 4 on the freighter that took us into Galway, its hold full of red horses that the islanders had swum out hitched to their currachs; they strapped them into harnesses and hoisted them aboard; in Londonderry in the bus station across from the main British Army base where my friend and I watched a returning five man patrol running double time, their automatic weapons centering on us just for a moment when they came around the corner. Seamus Heaney is dead. This is a mournful day.

Dr. Lewis, my Irish Literature professor, a good man and teacher, introduced me to his poetry when I was 19; Heaney’s earth-bound words, edged like flint, bore me into his lines. When I read his poems aloud, his nouns and verbs made me a little delirious in their combining sounds: rump, squat, spade, drills, lug, bog, corked, nicking, sweltered, gargled, slobber, sods, clotted, croaked, rank, pulsed, plop, blunt, spawn, clutch, knot, jam-pot, byre, smelt, furrow, stanched, muck, clabber.

We walked through a poor Ireland, before the Celtic Tiger, and the one lane roads where we waited for rides looked out over bog land, peat farms, brown cows and horses, and sheep everywhere and stone walls wilding in rhombi and elongated polygons and mustering into high palisades. We passed dozens of tiny, roofless, ruined, stone houses from the time of the Famine *. Heaney’s language describing farms and the farming life had room in me there to muddle about without the distraction of suburban sprawl or routine comforts. We ate and drank in isolated pubs, listening to the spoken word of the locals and to Friday night music. We slung our tent in empty lots, and the farmers and their wives would often invite us in for tea and biscuits and talk. I do not remember televisions. The rhythms of their speech was still their own, and it was Heaney’s rhythm.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day/ Than any other man on Toner’s bog. Once I carried him milk in a bottle/Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up/To drink it, then fell to right away/Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods/Over his shoulder, going down and down/For the good turf. Digging.**

And again:

My father worked with a horse-plough,/His shoulders globed like a full sail strung/between the shafts and the furrow./The horses strained at his clicking tongue./An expert. He would set the wing/And fit the bright steel-pointed sock over without breaking. At the headrig, with a single pluck/Of reins, the sweating team turned round/And back into the land. His eye/Narrowed and angled at the ground,/Mapping the furrow exactly. ***

A few years later he summoned my memory of our slow bus trip through fractured Derry the afternoon before Orange Day, through streets divided in half by high cement block walls topped with razor wire, graffiti telling us who lived on either side: “Up The Provos” and “Welcome To Loyalist Derry”. We stopped at many British road blocks and two soldiers in red berets would climb aboard, the second man holding his weapon high on the shoulder, the barrel down, but I remember his eyes having been so hot and alert. The first man walked front to back gazing at all the men, us too, asking for identification papers, licenses, passports, us too. Outside another soldier moved a long collapsible pole under the bus. It held a mirror on its end. He was trying to see if a bomb had been fastened underneath:

He was blown to bits/Out drinking in a curfew/Others obeyed, three nights/After they shot dead/The Thirteen men in Derry./PARAS THIRTEEN,the walls said./BOGSIDE NIL. That Wednesday/Everybody held/His breath and trembled. #

Now, 37 years after our ramble, having recently discovered our family’s genetic link to the North of Ireland, having previously known that the Walls and the O’Donnells both had roots in the South, Heaney means even more to me, his poems a personification of both my history and longing, his language an inspiration. I never met him and yet I feel as if I had. Seamus Heaney is dead. This is a mournful day.

* “For the Commander of the Eliza“

**From “Digging”

***From “The Follower”

#From “Casualty”