The news anchor, barely masking her agony, asked the experts to explain. The two men were stunned but controlled; they were attempting to account for the end of the world. One said that mass school shootings are “extraordinarily rare”; the other that schools are among “our safest places”. Both assertions appear to be true, but no parent this weekend cares about whether statistics bear out these claims; no parent cares about the low probabilities as to where and when yet another end of the world might occur. This weekend there is only one mathematical formula that is relevant for anyone who loves children: One child is equivalent to my child for my child might have been any of those children at Sandy Hook Elementary. The President said it best: “Our hearts are broken today [for] these children are our children.”

Now, in school offices all over the nation, worried men and women will come together and grapple with the most practical details of how to protect children from the conceivable horror; they will have to imagine scenarios, envision killers, set a plan on paper, and then later present that plan to larger rooms full of other worried men and women — parents and teachers … and children too.

In their heartache over lost children and teachers, the planners will have to study the murderer.

On another newscast, one little boy being hurried away from the fire station by his mother stopped to say that “We had to lock the door [of our school room] so the animal couldn’t get in.” That little boy’s metaphor describing what came into the school is understandable. We cannot venture inside an animal’s motivation; we cannot see into its mind.

However, the murderer was a human being and those charged with protecting children do not have the luxury of using metaphors. Their problem is one of trying to figure out how to see that which is invisible. They have a terrible dilemma to consider: no definition of nihilism can satisfactorily explain why Adam Lanza did this because definitions have logical progressions; they imply cause and effect. A parent of a surviving child said, “We aren’t equipped to deal with this.” She’s right. I’m not sure we’re equipped to understand the why. Even if he were alive to tell us, his reasoning would make him sound alien. Adam Lanza is one more American Stranger with a gun, another blank, another incomprehensible being. Place an armed, experienced police officer at the door of every school in America, and you will never find one who can see through the thousands of faces who yearly show themselves and into all those minds and to the kindness or the poison they might be bearing as their missions.

But they will have to try to set up a way to see. They have no choice. The messages have already been flowing back and forth among Superintendents and School Board members, between Principals and teachers. They have already been circulating in their uncountable numbers among mothers and fathers – is our school safe enough? what shall we do? what shall we say? what is wise? what will work?

In their planning sessions there is one factor that they can rely upon. Just as police officers by training and by nature will run toward a gun shot, teachers, by nature, will run toward a child in danger. Remember this: teachers is a wide category and includes anyone who comes into that school each morning to work directly with kids – coaches, aides, custodians, crisis counselors, nurses, principals, vice-principals, and classroom teachers. It doesn’t matter that on a normal day they might be stoop-shouldered and soft-spoken, or a wheezing, barrel-bellied physical wreck, or tiny, or prim, or brassy or a quarter-crazy. If someone threatens one of their students, they will shield their children with their bodies. They will turn and fight. They will become lions. Victoria Soto, Lauren Rousseau, Dawn Hochsprung, Mary Sherlach and other Sandy Hook teachers as yet unnamed represent the blessed normality of the profession.

Finally, God help us, everything circles back to three words, and even to say the three words twenty children dead sounds obscene, as if the speaker should hang his or her head and ask for forgiveness. The police will publish their names soon. Photographs will accompany the names. I cannot write those names or speak them aloud. Some things are better left to silence and to its shared, overwhelming grief.

Finally, God help us, everything circles back to three words, and even to say the three words twenty children dead sounds obscene, as if the speaker should hang his or her head and ask for forgiveness. The police will publish their names soon. Photographs will accompany the names. I cannot write those names or speak them aloud. Some things are better left to silence and to its shared, overwhelming grief.

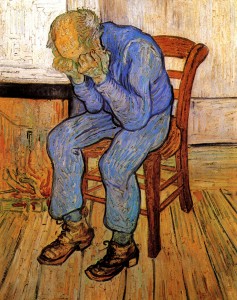

Vincent van Gogh: Old Man in Sorrow, 1890