An image is a picture. We see it in words and then make it in our imaginations. We remember its sound, taste, touch or smell.

A poetic image is inherently mysterious. It holds something back, but the reader can feel qualities beyond that initial form. When we call upon our experience, both lived and read, the image begins to transform, like the mutation of a creature within a pupal sack, one of those white silk creations we uncover behind the bark of a tree. We know that another life is stirring inside it, but we must wait just a bit for its revelation to be made apparent.

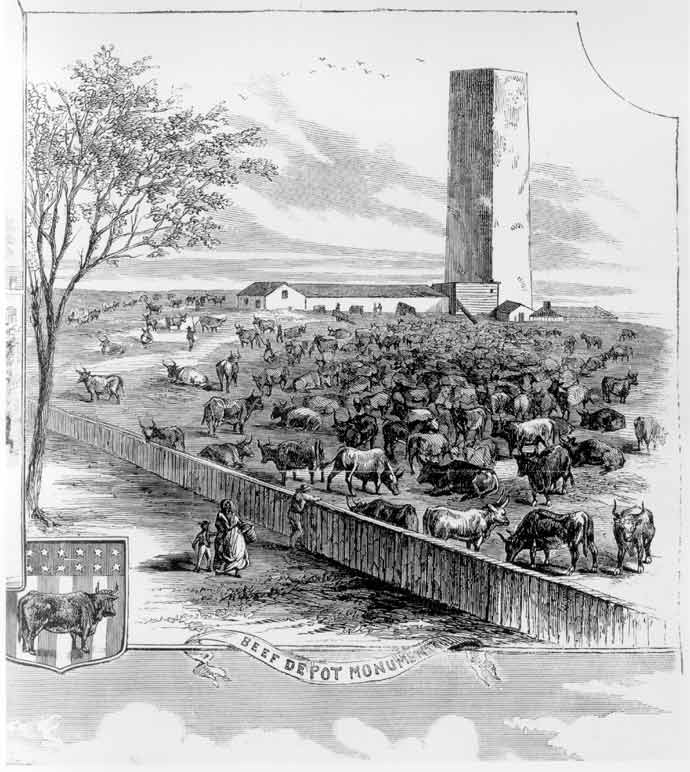

In “From Trollope’s Journal” Elizabeth Bishop remakes the novelist Anthony Trollope’s experience covering our Civil War in the winter of 1861. Trollope is walking about a “sad, unhealthy… raw and dark … half-ice, half-mud” Washington. On Pennsylvania Avenue he comes across cattle:

In “From Trollope’s Journal” Elizabeth Bishop remakes the novelist Anthony Trollope’s experience covering our Civil War in the winter of 1861. Trollope is walking about a “sad, unhealthy… raw and dark … half-ice, half-mud” Washington. On Pennsylvania Avenue he comes across cattle:

“There all around me in the ugly mud

— hoof-pocked, uncultivated — herds of cattle,

numberless, wond’ring steers and oxen, stood:

beef for the Army, after the next battle.

Their legs were caked the color of dried blood;

their horns were wreathed with fog. Poor, starving, dumb

or lowing creatures, never to chew the cud

or fill their maws again.”

Bishop makes use of our background understanding of the state of the War in 1861 — the Union losing badly, a dispirited army, the bloody awfulness of the casualty lists becoming real. Her image of the cattle, waiting for their deaths, uncultivated and poor, and her use of the words pocked, blood, ugly bring to mind what awaits the Army in the spring and for years to come. Her direct image of doomed cattle is transformed in our imaginations into the doomed men. The image acquires a terrible poignancy. It breaks outward into other meanings and does so without strain but subtly. It breaks through its original form into our lives. It registers as both historical and personal.

Because of its use of compression, poetry can be the most emotionally direct art. It distills the forces of love, pity, fury, loss, any of the emotions, into an essence powerful in its ability to affect us on the deepest levels and for a long time.

In “From Blossoms” Li-Young Lee finds an image that compresses the complexity of joy, the emotion we most desire, into only four stanzas. Echoing Proust’s eating of a madeleine, when she bites into a peach, she strikes an epiphany. She captures joy’s threads of elation and calm and sensual happiness, its steadfast opposition to death, its endurance in memory. Her wonderful first stanza uses a falling rhythm pushed on by alliteration that ends with the pure pleasure of the word that sends her into a rapture. Rhythm matches with melody. The pleasure is made manifest in the sound of the sentence:

From blossoms comes

this brown paper bag of peaches

we bought from the boy

at the bend in the road where we turned toward

signs painted Peaches.

From laden boughs, from hands,

from sweet fellowship in the bins,

comes nectar at the roadside, succulent

peaches we devour, dusty skin and all,

comes the familiar dust of summer, dust we eat.

O, to take what we love inside,

to carry within us an orchard, to eat

not only the skin, but the shade,

not only the sugar, but the days, to hold

the fruit in our hands, adore it, then bite into

the round jubilance of peach.

There are days we live

as if death were nowhere

in the background; from joy

to joy to joy, from wing to wing,

from blossom to blossom to

impossible blossom, to sweet impossible blossom.

A poem can deliver an instant snapshot of consciousness, specifically of imagination intersecting with the real world, and metaphor* is the bridge that allows that intersection to be vivid and rich in possibilities.

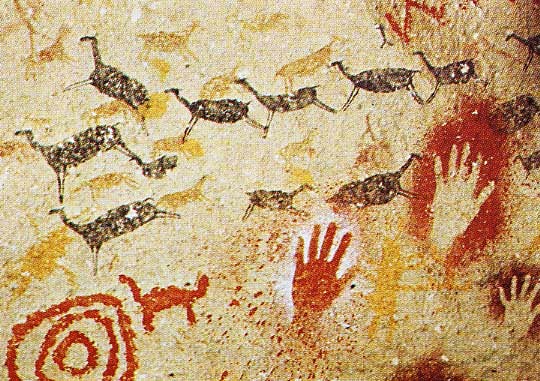

An effective metaphor works like a metaphysical jolt of energy. The metaphor strikes our memory and pushes out associations. It provokes our symbolic intellect. Think how often in conversation a person uses a simile to more fully describe an experience or another person or animal. Think of the cave paintings of Chauvet and Altamira and the religious and magical values of their horses and lions and those wonderful hands. Our minds seem hard-wired to create metaphors because we often mean more than can be said one way. Our minds vibrate so profoundly with their rivers of images and emotions and ideas that nouns and verbs alone generate their long lists of associations and figures. What comes to you when you think “skull” or “horse” or “heart”; “Achilles” or “Appomattox” or “Rome”?

Metaphor compels us to see and feel meanings — personal, historical, textual. Metaphors are naturally expansive. We make initial connections. Those connections branch out into others.

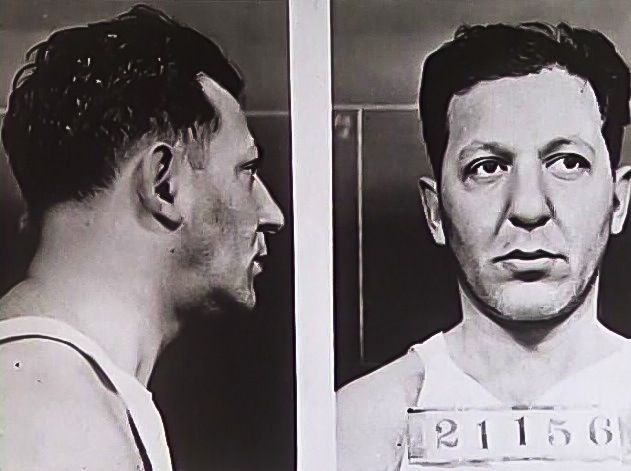

In Robert Lowell’s “Memories of West Street and Lepke” Lowell recalls his time in jail for being a CO. He shared a facility with Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the lead killer of Murder Incorporated, the enforcement arm of the Mafia in New York City in the 20’s and 30’s. He was executed by electric chair in 1944. The last stanza of the poem sketches Lepke as

In Robert Lowell’s “Memories of West Street and Lepke” Lowell recalls his time in jail for being a CO. He shared a facility with Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the lead killer of Murder Incorporated, the enforcement arm of the Mafia in New York City in the 20’s and 30’s. He was executed by electric chair in 1944. The last stanza of the poem sketches Lepke as

Flabby, bald, lobotomized,

he drifted in a sheepish calm,

where no agonizing reappraisal

jarred his concentration on the electric chair—

hanging like an oasis in his air

of lost connections….

This image of Lepke shapes a metaphor with multiple strands organized around the words lobotomized, sheepish, connections and oasis. It implies an historical knowledge of Lepke’s history, and a personal relation to our own knowledge and experience of these words, and to our implicit association in the decency of Lowell’s readers. Adopting Lowell’s point-of-view, we too are distanced from Lepke. We are not like him. Lowell keeps that distance. Part of what he is doing is showing how Lepke moves through his daily life in jail and then using those actions to try to figure him out. Thus the metaphor, the bridge hoping to connect the unimaginable Lepke to our reasonable lives.

Lepke, the killer who had dispatched men with ice-pick, garrote and revolver, is a man physically and morally lobotomized, disconnected from other human beings, conscienceless all his gangster life and rendered as dim as a sheep by the medical procedure, his calm so at odds with his past actions. In Lowell’s imagination, death is an “oasis” for Lepke, but unnaturally so — how could we project the electric chair as an “oasis” for ourselves? Oasis suggests sanctuary, a relief from wasteland, an entrance into a place fertile and green. Lepke’s life has been a wasteland. Perhaps his entrance into death would be the relief (for Lowell it would be). Electricity will surge through “connections” to kill him. In addition, his whole life has been a matter of “lost connections” with normal human beings, with normal existence where murder is abhorred, not taken as a matter of daily business.

Metaphor is proof of the endless dimensions of the world. Our inexhaustible imaginations combine with the inexhaustible realities of matter and life and those link up to the inexhaustible complexity of which our skill with language is capable. Metaphor is the inevitable result of all those kinships. Poetry is its natural home for it too is inexhaustible in its capacity to delight and inform our rapacious curiosities.

*any of the figures of speech that make use of contrast/comparison: personification, simile, metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche.

Loved this essay, Mike. Especially poignant to me was the Chinese poem about peaches. Hope some aspiring English teacher makes use of it.