No one does it alone. Not as a police officer, baker, cabinet maker, or teacher. Stepping back into time, we all can glance to our right and left and see the robust lives of those who went out of their way to teach us or whose solid presence and example provided the spur we needed to become more resilient and more attentive.

No one does it alone. Not as a police officer, baker, cabinet maker, or teacher. Stepping back into time, we all can glance to our right and left and see the robust lives of those who went out of their way to teach us or whose solid presence and example provided the spur we needed to become more resilient and more attentive.

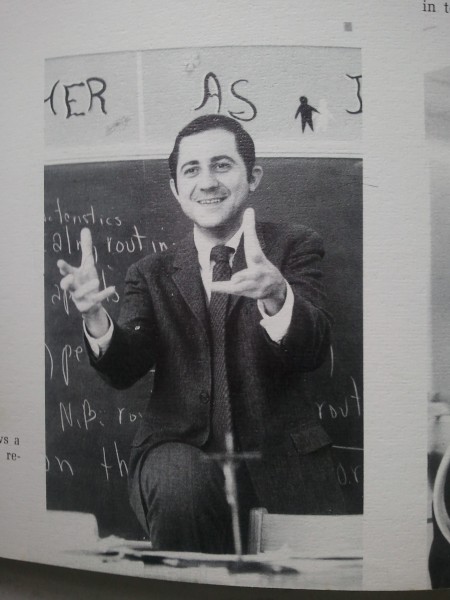

Mr. Dobroskey, 1970

Whatever I accomplished as a teacher, it had its manifold beginnings in the authority and poise of so many others – all those IHM Sisters who took on enormous Grammar school classes and helped train children who could both put away their beastliness and also concentrate for long periods of time; to Roger Breidinger and Joe Edwards, kindred spirits and opposing spirits both, one creatively brilliant and soft-spoken and the other a jester and brawler, united by their devotion to excellence and to doing absolutely right by the students and athletes in their charge; to Evelyn Lawrence who taught me all the rudiments of writing; to Jean Shervais, my compatriot, who sometimes rescued me from myself and whose rigorous professionalism was on display right next door for 34 years; to Dr.’s Watkins, Harris, Brown and Johns, respectively, professors of Philosophy, Irish Literature (twice) and Wilderness Studies, men who showed me how to think, read deeply, see and climb actual mountains, not just the metaphoric kind; to Norbert Haussmann, a man with an eighth grade education, my boss for four years as a custodian in college. He taught me how to clean a blackboard, sweep a room, do every little thing the right way and who spoke to me as if I mattered; and finally to Mr. Dobroskey, my senior religion teacher and perhaps the most influential of all.

Mr. Dobroskey met a senior class in 1970 filled with the turmoil of a country on fire – a rebellious, very smart, athletically talented, often arrogant bunch who had dealt its portion of misery to other teachers. He had no problems with us. He had the gift of the quiet effect, the subtle touch, and also the instinctive confidence of authority, both the poise and the skills. He knew how to explain abstract concepts so that they became concrete – sin, guilt, faith, and all the nuances of ethics were released from dogma and rote responses. He never preached to or patronized us. He knew that we were full of questions. He gave us the freedom and space to not only ask those questions but to challenge the Church’s accepted answers. He allowed us to begin making our own minds more agile.

In the classroom, he was a thoroughly decent human being. Never afraid, he never had to wield an autocratic power. We spoke more than he did. He knew how to make a class into a small community, one which listened to each other, one where logic and the elegance of reasoned argument outplayed any sense of peer conformity and disarmed lethargy. Here is where I began to learn how thrilling it could be to think about difficult ideas and how precise one had to be in the use of language.

If we are lucky, we get to spend time with those who have a peculiar light in their eyes, the kind of light which signals that they have resisted being stamped into place by the usual collective molds. They find a calling which may not have paid much but because of that offered them the chance to think more generously and openly than others. They came to possess the minds and actions that developed into worthy exemplars for us. Mr. Dobroskey was one of those individuals (and I am confident remains so). How fortunate we were, at 17 and 18, to fall under his graceful dominion.