Ahab is the soul of Moby Dick, but the physical and symbolic reality of the whale gives us the core ideas of the book. No other novel in American literature presents us with a more complex, poetic, and convincing portrait of a species or of an individual creature. The White Whale is the object of desire, the ferocious grail of Ahab’s quest.

Ahab is the soul of Moby Dick, but the physical and symbolic reality of the whale gives us the core ideas of the book. No other novel in American literature presents us with a more complex, poetic, and convincing portrait of a species or of an individual creature. The White Whale is the object of desire, the ferocious grail of Ahab’s quest.

He takes arms and legs, drags boatloads of men into oblivion and in attacking them purposely, smashes other boats into pieces. He cracks open the Pequod; she sinks with all hands but one. He is said to be ubiquitous, immortal, and the personification of “retribution, swift vengeance, eternal malice (819).” * He hunts those who hunt him.

This novel spares us nothing: whales are hunted, stabbed again and again with a lance until the heart or lungs are destroyed; they die in a ‘flurry’ of blood and then are skinned, chopped up, and boiled until all their essence become oil that lights a lamp. Melville saw the barbaric act clearly as framed by Stubb’s actions: “that a man should eat a newly murdered thing of the sea, and eat it by its own light (433).”

We might even think of Moby Dick as a horror story in its detailed scenes of ferocious carnage. How else are we to make contemporary sense of passages like this one which describes the butchering of a whale: “for a moment or two the prodigious blood-dripping mass sways to and fro as if let down from the sky (419).” Or this one, so appalling to Ishmael that he must turn away from describing it: “for it were simply ridiculous to say, that the proper skin of the tremendous whale is thinner and more tender than the skin of a new-born child. But no more of this (442).”

We have hunted and eaten animals since our precursors left the trees and stood upright on the savannah, about 2 million years ago. We have made their flesh and bone into shirts and dresses, bed-coverings and containers; worshipped their spirits, embalmed their bodies, bred and domesticated them, drawn and painted and sculpted them; envied their freedom, ferocity, nobility and obedience, and equally damned their freedom, ferocity, deceitfulness, and gross habits. They have been our alternate selves, our embodiment of human virtues and vices, our spirit-selves, our omens, our prey. Sometimes, as if to allow us space for even more imaginative archetypes, they have hunted and eaten us.

For example, the Inuit reported that when polar bears stalked them on the open ice, they used their white coat to blend with the horizon line, they crawled toward them on their bellies  just before a charge, and while crawling, they hid their black noses with their paws. Before the rifle, one imagines that the bears often succeeded. Melville did not hesitate to describe a similar context for our most common bond with animals: “For we are all killers, on land and sea; Bonapartes and sharks included (204).”

just before a charge, and while crawling, they hid their black noses with their paws. Before the rifle, one imagines that the bears often succeeded. Melville did not hesitate to describe a similar context for our most common bond with animals: “For we are all killers, on land and sea; Bonapartes and sharks included (204).”

Moby Dick: Matt Kish

The Inuit completed the circle. They cut a piece of flexible whale-bone into a spring, sharpened both ends, folded it, froze it in blubber and set it out as bait. A polar bear might swallow it whole. They followed the beast. Its feces began to show signs of blood. Signs turned into puddles. After a few days, the hunters arrived at the carcass, its face frozen into a rictus of pain.

Killing alone does not define the relationship. Animals may have also prompted our species’ ascent into some being distinctly unbrutish – a creature curious, brilliant, reflective.

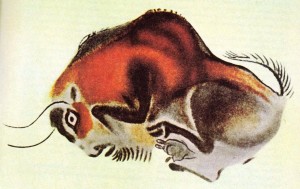

Our ancestors began to transform animals through the creation of physical images. They took what they had seen and killed and dreamed of and heard about in stories, and they climbed deep into caves, into secret places, and they created something that “spoke a language of symbolism (197).” ** This happened “in glaciated Europe around 40 thousand years ago when an extraordinary gallery of cave paintings suddenly effloresced (208).” **

These “paintings suddenly filled France and the Pyrenees much as cathedrals did medieval Christendom (209).” ** Over 150 sites have been discovered. After seeing the paintings at Lascaux, Picasso shook his head in wonderment and said, “We have invented nothing.”

These “paintings suddenly filled France and the Pyrenees much as cathedrals did medieval Christendom (209).” ** Over 150 sites have been discovered. After seeing the paintings at Lascaux, Picasso shook his head in wonderment and said, “We have invented nothing.”

A painting of a bison from Altamira, 16,000 BCE

Deep inside the caves “walls radiate drawings of the era’s mega-fauna – Auroras, red deer, ibex, and horses … cattle, birds, felines, bears, rhinos, mammoths, lions … human hunters … abstract emblems (209).” ** Melville works within this tradition – his whales are frequently a source of awe and mystery, the White Whale chief among them.

Moby Dick is filled with scenes of mystical efforts at connection with whales and with transcendent beauty – witness the heads suspended on either side of the ship, a spell to ward off capsizing; Ahab’ s monologue about the revolutionary wisdom of what the head of a dead whale carries within its experience; the enchantment of the ‘”nursery” sequence in the chapter “The Great Armada”.

In the midst of a frenzied hunt taken against a large pod of sperm whales, Ishmael’s boat is drawn into the middle of dozens of calves and their mothers. They dare not attack them for  fear of being crushed. They are forced to quietly and slowly try to find their way out of whales who “like household dogs … came snuffling round us (559).” Ishmael describes seeing a “wondrous world” that left him “entranced.”

fear of being crushed. They are forced to quietly and slowly try to find their way out of whales who “like household dogs … came snuffling round us (559).” Ishmael describes seeing a “wondrous world” that left him “entranced.”

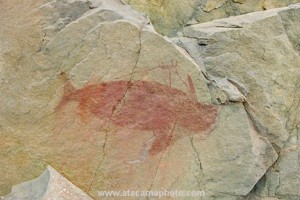

Ancient painting of a whaling scene from Medano, Chile

Ishmael also seems to have had his own moment of dream-time about the creature he is to hunt before he even knows that the Pequod, Ahab or Moby Dick exists.

On page 8 of chapter one, Ishmael, telling the story of the voyage he alone survived, invokes the first allusion to Moby Dick, and he frames it as a visionary moment, almost hallucinatory in the way he receives it: “in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.” The context of the paragraph implies that he experienced this vision before the voyage. One could argue that his long tale inexorably unfolds from his trance – in his “inmost soul” he summons the White Whale, the creature who gives the novel its name.

Maybe the best way to understand the novel in 2012 is a tragedy not of Ahab so much but of our temperament as human beings. Trace our history: we initially hunted to feed and clothe ourselves. At that point evidence indicates that we often thought of animals as sacred, as holy messengers, as emissaries of the gods or as gods themselves. Hunters paid respect to the hunted. Then sustenance-hunting yielded to a change in perception; animals were consumed as an industrial commodity. Our awareness of the quality of holiness in them deferred to our desire to acquire bone, blubber, and oil. How we did so did not matter. Only efficiency mattered. For example, one of the most awful scenes in the book involves Flask, the third mate, one of a breed of new men – unreflective, cocky, ignorant, and unthinkingly cruel. He sees an ulcer on an old bull they have attacked. He cries, “A nice spot … just let me prick him there once (518).” In spite of Starbuck’s cry to stop, Flask strikes. The whale dies in anguish: he “lay panting on his side, impotently flapped with his stumped fin, then over and over slowly revolved like a waning world (518).” His suffering does not matter to Flask. Only the efficiency of the kill is important.

just let me prick him there once (518).” In spite of Starbuck’s cry to stop, Flask strikes. The whale dies in anguish: he “lay panting on his side, impotently flapped with his stumped fin, then over and over slowly revolved like a waning world (518).” His suffering does not matter to Flask. Only the efficiency of the kill is important.

A print of a hunt from the Pacific

However, a traditional horror story requires a world caught up in a battle between villains and heroes. It is often a Manichean world, a story taken from melodrama. Melville is after something more audacious. He presents the White Whale as an ambiguous demi-god.

Moby Dick is beautiful, deadly, a “dumb creature,” a “demon,” a mighty animal hunted into madness, a representative of “the heartless voids (282),” “a living opal (374),” a victim, an intelligent mammal that defends itself from violence, an “intelligent malignity (264),” a “phantom,” the repository of a supernatural evil, an assassin (819), a follower of hidden pathways in the seas, an individual possessed of a crooked jaw and a hump “like a snow hill in the air (8).”

Ishmael also grants him “a gentle joyousness – a mighty mildness of repose in swiftness ( 783).” Just before the climax of the book three consecutive paragraphs are replete with soothing and temperate words describing Moby Dick and the sea through which he swims (away from the Pequod) – words like “serenely, dazzling, sliding, finest, fleecy, soft, glistening, musical, rippling, danced, gay, canopy, streaming, glorified and divinely (783-784).” Then contrast all that with the observation that in “successive meetings with various ships” Moby Dick destroyed his hunters with “demonic indifference (766).”

Ishmael also grants him “a gentle joyousness – a mighty mildness of repose in swiftness ( 783).” Just before the climax of the book three consecutive paragraphs are replete with soothing and temperate words describing Moby Dick and the sea through which he swims (away from the Pequod) – words like “serenely, dazzling, sliding, finest, fleecy, soft, glistening, musical, rippling, danced, gay, canopy, streaming, glorified and divinely (783-784).” Then contrast all that with the observation that in “successive meetings with various ships” Moby Dick destroyed his hunters with “demonic indifference (766).”

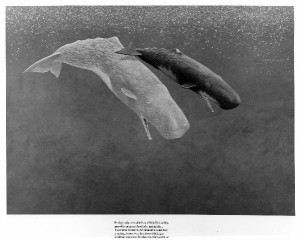

Moby Dick by Richard Ellis

Ishmael tells us that Moby Dick may a herald from “the invisible world,” those points-of-the-compass beyond our control or understanding, places that “seem formed in fright (282).” Yet, on the third day of the chase Starbuck cries out to Ahab, “See! Moby Dick seeks thee not. It is thou, thou, that madly seekest him (815)!”

All of these possibilities swirl within the text, rising and sinking depending upon a character’s perception of Moby Dick and our own 21st century sensibilities.

Who could write Moby Dick now except ironically? The psychological impact of big animals as a threat has receded as our species has grown in numbers and spread into and domesticated wilderness. In the past 162 years since its publication, we have explored, exterminated, analyzed, controlled, demystified, collared, and altogether dominated them. Now cheap stores sell t-shirts with their images framed in heroic or cute poses — wolves in packs on the prairie, bears with their heads raised, listening; tigers as cuddly as kittens.

Who could write Moby Dick now except ironically? The psychological impact of big animals as a threat has receded as our species has grown in numbers and spread into and domesticated wilderness. In the past 162 years since its publication, we have explored, exterminated, analyzed, controlled, demystified, collared, and altogether dominated them. Now cheap stores sell t-shirts with their images framed in heroic or cute poses — wolves in packs on the prairie, bears with their heads raised, listening; tigers as cuddly as kittens.

Moby Dick: woodcut by Rockwell Kent

Those images sell though, especially as big animals fade from our lives; in some way we feel our connection to them, to their long history as our allies in our search for meaning and transcendence. In 1851 Moby Dick would have been a terrifying specter come from a hard, mysterious natural world that many of those readers would have lived alongside and known intimately. Of course, the 20th century gave us human demons other than animals, and the 21st century has added to that list.

Still, the White Whale has taken hold of something in us. His image and name appear everywhere in our culture – in advertisements, in political and sports metaphors, in any number of venues as a standard of contrast and comparison. But those are surface appearances only. I think he endures as a more serious creation. In that gliding great spirit I think Melville created something much more daunting for us to consider. He looked into the abyss, and then he told the truth about what he saw there.

He sensed that something is profoundly wrong in the design of the world, that underneath our daily normalcy, we are always at risk of suffering and death, no matter our age or how we live, saint or sinner. While serving on a US Navy frigate, the United States, he had seen terrible floggings, a brutality often inflicted as an exercise in power. The overall tone of this novel makes it clear that as a whaler he had seen and participated in the hunting of creatures for whose suffering and destruction he felt pity. He had seen sharks at work on sea and on land. Perhaps Melville compressed all his philosophical and theological questions into this description: “when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and would not willingly remember, that this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang (703).” Ahab is mutilated by that “remorseless fang,” but instead of retreating, or accepting his suffering as Captain Enderby did, Ahab “piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his race from Adam down (267).” In his madness, Ahab mistakes the White Whale for the devil, but he did not make a mistake, nor did Melville, in understanding that no one is safe, that there is no sanctuary, that beneath the smiling surface of our lives, claws and teeth have been sharpened, and that on the sunniest day, anyone’s blood may be shed.

http://www.mobydickbigread.com/ : The best selection of audio recordings from the novel that I have found.

* Moby Dick Or The Whale by Herman Melville: Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. Random House: New York, 1930.

** The Last Lost World: Ice Ages, Human Origins and the Invention of the Pleistocene by Lydia and Stephen Pyne