How does one come to a comprehensive understanding of mysterious Ahab, a man dismembered, besieged by blasphemous insights, a prisoner of his own self-imposed solitude, a living force isolated by a brilliant mind focused on the annihilation of a “great, gliding demon?” Contemptuous of all dogmas and fearless, he believes that “the right worship is defiance (725).”* Once begun, there can be no turning back – his pride will be extinguished when he dies, not before.

How does one come to a comprehensive understanding of mysterious Ahab, a man dismembered, besieged by blasphemous insights, a prisoner of his own self-imposed solitude, a living force isolated by a brilliant mind focused on the annihilation of a “great, gliding demon?” Contemptuous of all dogmas and fearless, he believes that “the right worship is defiance (725).”* Once begun, there can be no turning back – his pride will be extinguished when he dies, not before.

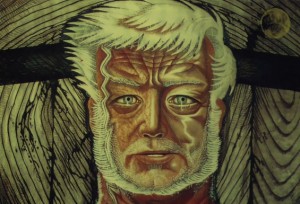

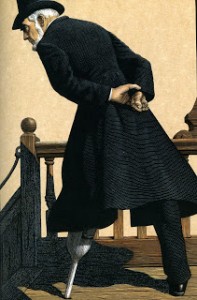

Pride, inflexible courage and an absolute defiance are terrible, exhausting burdens – how difficult never to rely upon faith, never to take some ease in tactical retreat, never to accept any authority except his own. Civilized enough to have married and father of a child in old age, at one point he had to have felt the weight of pleasure in his life, but after losing his leg, after a suffering-filled voyage home during which his “torn body and gashed soul bled into one another (268)”, he now “wears a crucifixion in his face (178).” His body bears further hieroglyphs of torture: “He looked like a man cut away from the stake.” He bears “a slender rod-like mark” that bisects his “scorched face and neck, till it disappear[s] in his clothing (177).”

ease in tactical retreat, never to accept any authority except his own. Civilized enough to have married and father of a child in old age, at one point he had to have felt the weight of pleasure in his life, but after losing his leg, after a suffering-filled voyage home during which his “torn body and gashed soul bled into one another (268)”, he now “wears a crucifixion in his face (178).” His body bears further hieroglyphs of torture: “He looked like a man cut away from the stake.” He bears “a slender rod-like mark” that bisects his “scorched face and neck, till it disappear[s] in his clothing (177).”

Unlike Ahab, Ishmael’s despair responds to Queequeg’s unquestioning kindnesses and acceptance; these break a pattern of consciousness that senses death everywhere. His rebellion against humanity, which took the form of misanthropy, is drawn out of him. Once a “looker on” and possessed of a “splintered heart, he finds deliverance in the friendship of an honorable cannibal, in a man incapable of deceit, devoid of ulterior motives. There is no friend who can reach Ahab. Starbuck comes closest to doing so, but he cannot penetrate the old man’s pride.

In The Rebel Albert Camus asserts that “the romantic rebel’s ambition is to talk to God as one equal to another (55).” Ahab asserts that prideful right.

Another strong contrast to Ahab, Father Mapple, in his sermon on Jonah, proposes that to “obey God” we must “disobey ourselves,” that “true and faithful repentance [is] not clamorous for pardon but grateful for punishment.” As a version of a Promethean rebel, Ahab will neither repent nor disobey himself. He will “strike the sun” if it offends him; one cannot imagine him quailing before “senators or judges”. But he rejects God as his judge. He is not an atheist but a person more dangerous, a believer who through his actions implies that mankind must revolt against natural and supernatural judgment and punishment. He preaches an equality of Ahab and God, and therefore he will not accept the unjust suffering he believes the universe inflicts upon humanity and has wreaked upon him. I sometimes believe that in his madness, he thinks himself to be the redeemer of those sins.

In a discussion of The Brothers Karamazov Camus writes about Ivan Karamazov’s spiritual rebellion: “If evil is essential to divine creation, then creation is unacceptable (55).” Ivan will “not admit that truth should be paid for by evil, suffering, and the death of innocents. [He] incarnates the refusal of salvation. Faith leads to immortal life. But faith presumes the acceptance of … evil and [a] resignation to injustice (56).”

will “not admit that truth should be paid for by evil, suffering, and the death of innocents. [He] incarnates the refusal of salvation. Faith leads to immortal life. But faith presumes the acceptance of … evil and [a] resignation to injustice (56).”

A pop-culture image by Joe Doubleclick

When Ahab meditates upon a decapitated whale’s head in the chapter “The Sphynx,” he imagines a catalog of cosmic injustices. He alleges a creation where “… locked lovers … leaping from their flaming ship” sink beneath “exulting wave[s]; true to each other when heaven seemed false to them.” He sees a ”murdered mate … tossed by pirates from the midnight deck … into … the insatiate maw” of the sea “and his murderers … sail[ed] on unharmed.” Simultaneously, “swift lightnings shiver[ed] the neighboring ship that would have borne a righteous husband to outstretched, longing arms (450).” By Ahab’s reckoning these are indictable actions. Someone must be brought to answer for the evil done to the good, for the myriad numbers made up of men and women like the mate and lovers and righteous husband. Ahab demands answers: “Where do murderers go, man! Who’s to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar? (778-779).”

Ahab declares himself to be both judge and executioner, a predator who hopes to erase the pain of his wound with blood. Sailing in a vessel named for a genocidally erased tribe, “a cannibal craft, tricking herself forth in the chased bones of her enemies (101),” Ahab “lived in the world as the last of the Grisly Bears lived in settled Missouri (219),” a carnivore among men. He taps into the routine of savagery that permeates every part of their hunting process and welds that savagery to his militant purpose.

Stubb and Flask are mediocrities and men inured to taking orders, both unthinking believers in the hierarchy of earthly power where a captain of a ship is a lord. They would not oppose him.

Starbuck, the first mate, would seem to have the best chance to challenge him successfully. He rails at Ahab for his blasphemy, and finally stands outside Ahab’s cabin, musket leveled to  Ahab’s head, preparing to murder him, but his courage is “a thing simply useful to him (162)”, a utilitarian device, and therefore not a moral resource. It may be used in the hunt but cannot be mustered to meet Ahab’s philosophical obsession. Starbuck can “confront the ordinary, irrational horrors of the world (164)”, but only an anti-Ahab, a sane, obsessively good twin, might have been able to stop him. Even Ishmael, befriended by Queequeg, capable of empathy, moved by beauty — even he accepts Ahab’s logic.

Ahab’s head, preparing to murder him, but his courage is “a thing simply useful to him (162)”, a utilitarian device, and therefore not a moral resource. It may be used in the hunt but cannot be mustered to meet Ahab’s philosophical obsession. Starbuck can “confront the ordinary, irrational horrors of the world (164)”, but only an anti-Ahab, a sane, obsessively good twin, might have been able to stop him. Even Ishmael, befriended by Queequeg, capable of empathy, moved by beauty — even he accepts Ahab’s logic.

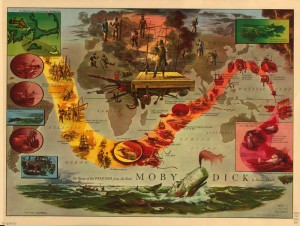

A map of describing the voyage of the Pequod: Everett Henry, illustrator

Ahab disguises his intentions. He will seem to go to sea for treasure but actually goes out of a lucid madness, a twisted and clear desire for vengeance. To accomplish this he had to have plotted long before he left for the voyage. He kept his plan from the owners of the ship, Bildad and Peleg, from his first mate, presumably from his wife. He carried his dream of vengeance like a desire unspoken to others, hidden — it became a cancer that sustained him.

Ahab draws all to him. His actions in “The Quarterdeck” show someone theatrically aware, one who uses the sound of his ivory leg while he paces to make the crew aware of his spellbound presence and thus he builds suspense and sustains it — he waits until “near the end of day” to call them aft and break open what he wants them to see, the spell that holds him, whose intensity they feel even in his pauses. He will transfer his terrible purpose to them. To do so, he employs the engrained authority of his position as captain and the conditioned subservience of the crew. He knows how to manipulate them within their chosen purpose as whalers – his quest gives them a purpose that takes them beyond their individual selves. He gives them a spiritual reason to hunt Moby Dick and anchors it with an oath sealed by howls and rum.

Ahab pays special attention to Starbuck. He declares to him that all objects are “pasteboard masks” and therefore implies that they are mere trifles and easily smashed. We may know the nature of objects through their actions. Appearances lie. Ahab affirms that he knows their reality. He alone has the intelligence and the wound-enhanced perception necessary to see that Moby Dick, whether “principle or agent,” is an enemy of humanity and is the plague-agent of all “the subtle demonisms of life (267).” This is the individual reality that motivates him.

He intensifies the power of that vision by insisting the crew become a part of his quest. He must have them. Hunting whales is a communal effort. He cannot kill Moby Dick alone. He seduces his crew. He overpowers his mates. Something primal in his madness appeals to his harpooners.

His compares his single-minded purpose to a cog in machinery, to a match applied to powder, to a locomotive – all images of a catalyst, of the force that moves others rather than be moved. He casts himself heroically as a man who will say no to a corrosive, predatory universe, but he will not tolerate Starbuck to say no to him.

He bears the individual power of a personality madly focused. Ahab rejects any escape from his obsession. T.S. Eliot wrote that “human kind cannot bear very much reality.” A part of  Ahab’s madness is his resolve to bear all of it. With the exception of tormented Starbuck, the members of the crew seek escapes from the normal travails of the voyage and from their forebodings. They seek relief in the dreamy separateness bestowed upon lookouts on the mainmast, in communally squeezing the “inexpressible sperm” and feeling “divinely free from all ill-will (604)”, in the animal celebrations around the smoking try-works.

Ahab’s madness is his resolve to bear all of it. With the exception of tormented Starbuck, the members of the crew seek escapes from the normal travails of the voyage and from their forebodings. They seek relief in the dreamy separateness bestowed upon lookouts on the mainmast, in communally squeezing the “inexpressible sperm” and feeling “divinely free from all ill-will (604)”, in the animal celebrations around the smoking try-works.

Ahab wants no consolation for the loss of his leg, for his tormented heart. His “sweet, resigned girl,” his wife, nor his child, are able to mend him. He wants no relief. He wants to confront the terrible beast that tore him apart. He will again “burst his hot heart’s shell upon it (267)”; he will court the possibility of his own death and those of his men so as to take his all-embracing, personal vengeance. He is no knight come to slay the dragon. He is not St. Michael and Moby Dick is no Lucifer.

Ahab wants no consolation for the loss of his leg, for his tormented heart. His “sweet, resigned girl,” his wife, nor his child, are able to mend him. He wants no relief. He wants to confront the terrible beast that tore him apart. He will again “burst his hot heart’s shell upon it (267)”; he will court the possibility of his own death and those of his men so as to take his all-embracing, personal vengeance. He is no knight come to slay the dragon. He is not St. Michael and Moby Dick is no Lucifer.

He believes in an alternate, spiritual reality; he says to the carpenter that “some entire, living, thinking thing may … be invisibly and interpenetratingly where thou now stand (677).” He speaks to the head of the sperm whale of the sacred truths it could shatter if it were able to speak, of the secrets it knows that could “split the planets and make an infidel of Abraham (450).” He watches Queequeg carve his tattoos into the lid of his coffin-canoe, the tattoos that were the “work of a prophet and seer of his island,” and that spoke of “a complete theory of heaven and earth,” and represented a “mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth.” Unable to decipher his tattoos, Ahab bemoans “the devilish tantalization of the Gods.” Ahab wishes to be a destroyer of mysteries. He seeks to unmask and kill whatever vile, supernatural authority took his leg and preys upon human beings.

To do so he will destroy his crew. These are his great sins – he has lied about his voyage’s purpose, he has concealed his madness, he has converted the crew to his obsession and has made them into mere “wheels “ who will “revolve” at his command; he must make them into objects so as to destroy the greater evil he sees in Moby Dick. For Ahab, his end justifies barbarous means.

When Ahab refuses to help The Rachel’s Captain Gardiner search for his son, missing in a boat towed out of sight by Moby Dick, he crosses an unforgivable moral line. A fellow  Nantucket father pleads for only 48 hours of the Pequod’s time to find a lost child. A fellow Nantucket father refuses. Ahab will be damned by all if he lives to return. His drive to kill never allows even a moment’s hesitation: “Even now I lose time (762).”

Nantucket father pleads for only 48 hours of the Pequod’s time to find a lost child. A fellow Nantucket father refuses. Ahab will be damned by all if he lives to return. His drive to kill never allows even a moment’s hesitation: “Even now I lose time (762).”

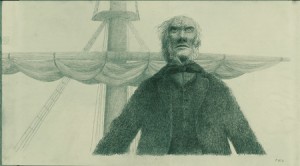

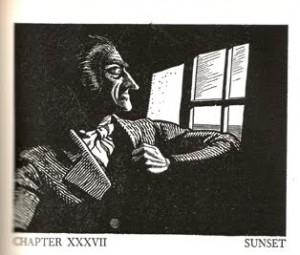

Boardman Robinson’s Ahab and Pip

But Melville will not let the reader damn Ahab so definitively; Melville keeps us aware of Ahab’s torment – a man so overwhelmed by his vision that he shouts out in his sleep, loud enough to be heard through the ship’s timbers, “Stern All! The White Whale spouts thick blood (693).” He is aware of his warping. He will “neither shave, sup nor pray (700)” until he has killed the white whale. Pointing to his “ribbed brow,” he asks Perth, the blacksmith, if he can “smooth this seam? Glad enough would I lay my head upon this anvil, and feel thy heaviest hammer between my eyes (699).”

In his heartbreaking conversation with Starbuck in “The Symphony” he speaks of his son: “About this time – yes, it is his noon nap now – the boy vivaciously awakes; sits up in bed; and his mother tells him of me, of cannibal old me; how I am abroad upon the deep, but will come back to dance him again (778).” Ahab commits monstrous acts but is no monster.

In his heartbreaking conversation with Starbuck in “The Symphony” he speaks of his son: “About this time – yes, it is his noon nap now – the boy vivaciously awakes; sits up in bed; and his mother tells him of me, of cannibal old me; how I am abroad upon the deep, but will come back to dance him again (778).” Ahab commits monstrous acts but is no monster.

He remains capable of the deepest pity. He grows to love Pip, the cabin boy driven mad by the sea; his heart is struck by his condition: “Oh ye frozen heavens! Look down here. Ye did beget this luckless child and have abandoned him (747).” He orders Pip and Starbuck to remain on board the Pequod during the final hunt. He tries to save their lives.

We cannot doubt his courage or the price so many will pay for its iron composition. We can see both the intractability of his “coiled woe,” and the indispensable power of “the cankerous thing in his soul (775).” “Firm and unyielding” and yet “tied up and twisted”; “gnarled and knotted with wrinkles” and yet possessed of “eyes … that still glow in the ashes of ruin (775).” He acknowledges that he is “more a demon than a man (776).” He has become a kind of Achilles, someone who has been steeped in 40 years of “madness, frenzy, boiling blood (776)”, but not so frozen into blood-lust that he cannot see Starbuck’s gaze as a salvation: “By the green land; by the bright hearthstone! This is the magic glass, man; I see my wife and child in thine eye (777)!”

His mania has not obliterated his humanity. At the end of “The Symphony”, speaking honestly and with depth of emotion to Starbuck, he conjures  this image of serene, paradisaical beauty: “But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay (779).” Starbuck has “stolen away.” It is too late. Visions of a mountain paradise cannot alter what has become embedded into Ahab’s character.

this image of serene, paradisaical beauty: “But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay (779).” Starbuck has “stolen away.” It is too late. Visions of a mountain paradise cannot alter what has become embedded into Ahab’s character.

Rockwell Kent’s Ahab

He is snatched from his boat by the line he has attached to Moby Dick, dead by the hand that flung the harpoon and that secured the line of rope to its blade. He could not have survived his search. Melville understood the terms Ahab had chosen: a mortal man believes himself to have unraveled a mystery unfathomable, the terrifying flaw built into the foundation of life – why do the innocent suffer? He believes himself alone to have seen to the heart of this secret. There he has found an agent, perhaps even the source of evil itself. He abandons love, duty, companionship, solace and any semblance of balance and moderation. He hammers his flesh and mind into a weapon. He pursues. He hunts. He hauls a score of others to their deaths.

Ahab is the great villain-hero of American literature, its most memorable tragic-killer, and it has been 48 years now since I first saw him appear on the quarter-deck of the Pequod. He claims me as he claimed the crew.

# I think Moby Dick is unfilmable. Film is not sophisticated enough to convey the nuances and context of mythic yet human characters. No one has been able to capture Ahab. However, John Huston’s 1956 version does show us scenes that enable our eye and ear to jump back to the mid-nineteenth century, nowhere more beautiful than in this sequence — spend time looking at the faces; the scenes of the sails and rigging are authentic — no CGI there; the singing is marvelous: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdiFYCUP9oU

* Moby Dick Or The Whale by Herman Melville: Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. Random House: New York, 1930.