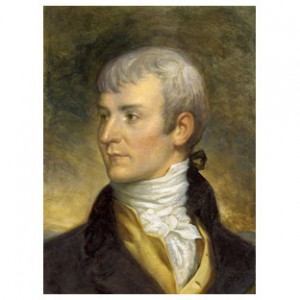

When I read The Iliad or The Odyssey the stories of the gods bore me to distraction. I skip pages, read at light speed, anything to get past their deep-grained dullness. Who cares about Zeus and Hera, trivial figures because of their extraordinary powers and immortality? If you can do just about anything and have all eternity to do it, what is the challenge, where is the edge that makes our own poor, screwed up, questing, human lives so compelling. We have our mortal bodies and our wits – that’s about it — and therefore figures like Meriwether Lewis command our attention, my attention. Because our heroes weaken and die, they might, in their best moments, flare up like suns in distant galaxies, so bright that every eye is drawn to their shining. Our heroes are never vague but always personal because they suggest to us what we would like to become, the actions we might hope to pursue, the classic, brilliant lives we dream of emulating. In these respects, Michael Deas’ portrait of Lewis catches his bearing of fortitude and also, in his fine features, his thoughtfulness.

When I read The Iliad or The Odyssey the stories of the gods bore me to distraction. I skip pages, read at light speed, anything to get past their deep-grained dullness. Who cares about Zeus and Hera, trivial figures because of their extraordinary powers and immortality? If you can do just about anything and have all eternity to do it, what is the challenge, where is the edge that makes our own poor, screwed up, questing, human lives so compelling. We have our mortal bodies and our wits – that’s about it — and therefore figures like Meriwether Lewis command our attention, my attention. Because our heroes weaken and die, they might, in their best moments, flare up like suns in distant galaxies, so bright that every eye is drawn to their shining. Our heroes are never vague but always personal because they suggest to us what we would like to become, the actions we might hope to pursue, the classic, brilliant lives we dream of emulating. In these respects, Michael Deas’ portrait of Lewis catches his bearing of fortitude and also, in his fine features, his thoughtfulness.

Lewis and Clark are forever joined. They could not have accomplished alone what they did together. On the courses of the Missouri and Columbia, they covered over 6000 miles of country. Lewis walked thousands of miles. Hunting and scouting ahead, he preferred the banks of the Missouri to the keelboat. Both wrote continually and left behind 13 volumes of their journals. Clark’s maps are superb in their accuracy. Lewis wrote lengthy descriptions of flora and fauna, landscapes and peoples. Try to imagine them as professors who were also able to ride, shoot, fight, hunt, negotiate with Native Americans, and command tough men, primarily through their example.

They traveled over thousands of miles of unknown territory and endured terrible winters, bouts of sickness, an awful crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains at the cusp of winter, cold, wet conditions, exhaustion, and threats from hostile Native Americans and did all this without recourse to rescue, dependent only upon their own resources. In doing so they lost one man over two and one half years of trave,l and that man probably died of a burst appendix which no one on earth at that time could have healed.

Their leadership inspired their independent-minded Corps of Discovery to become a superb unit. Lewis, inspired by Shakespeare’s St Crispin’s day speech from Henry V, thought of them as a “band of brothers.” The rough average age of the Corps of Discovery members was 29. In 1804 terms that describes men in the prime of their lives, strong frontiersmen and soldiers, but Lewis and Clark shaped them into a disciplined, smoothly functioning team from start to finish – a feat of leadership that could not have been inspired by martinets or dictators but only by commanders who shared their struggles and suffering and who showed themselves to be their equal, and in Lewis’s case especially, their superior in stamina, toughness and courage. Clark was convinced that the men of the Corps of Discovery were in awe of Lewis, a man whom Clark thought of as without fear (Lewis was 29 when he began the journey, an equal in age to his men. He had to have possessed that magnetism that some leaders carry with them

as a natural portion of their persona).

Clark is the easier of the two to know, the more successful one in adapting to an after-journey life (two wives, ten children, wealth). He was easier with men and women, less detached, less inward. He was an admirable man, but not completely so. His treatment of his slave, York, who accompanied him on the Journey, limits our admiration. York desired freedom and to return to his wife and children who had been sold to another master. According to Clark, he “sulked.” Clark went so far as to beat the man who had tended him in his many physical miseries on the Journey.

Lewis captured my imagination. His writing illuminates a sensibility that took the most sincere delight in new places and who sought the deepest absorption in the natural world. In one of his journal entries Lewis tried to describe what he had seen on the northern plains and in the Shining Mountains (the Rockies). He used the phrase “scenes of visionary enchantment.” More than any of the other men, he seemed to be able to see nature in terms other than the merely practical, but as part and parcel of a deeper “beauty”, a form of the word he uses again and again in his journal entries. Lewis took delight in new country; he loved the “visionary enchantment” of each new vista of rivers, mountains and plains.

Lewis captured my imagination. His writing illuminates a sensibility that took the most sincere delight in new places and who sought the deepest absorption in the natural world. In one of his journal entries Lewis tried to describe what he had seen on the northern plains and in the Shining Mountains (the Rockies). He used the phrase “scenes of visionary enchantment.” More than any of the other men, he seemed to be able to see nature in terms other than the merely practical, but as part and parcel of a deeper “beauty”, a form of the word he uses again and again in his journal entries. Lewis took delight in new country; he loved the “visionary enchantment” of each new vista of rivers, mountains and plains.

Having been schooled for a year in Washington and Philadelphia before the journey and especially through his studies in botany, zoology, ethnology, astronomy, mathematics, his intellectual senses were sharpened to a fine blade. He made his mind and body into this perfect explorer, someone trained to be astonished, to take note of his astonishment, to record the facts that gave the scenes of his astonishment their shape and precise movement and behavior.

One journal entry for one day brings many of his best physical and intellectual qualities alive. On July 3, 1805, Lewis stood on a hill over “the watery bosome of the missouri” and saw “vast flocks of geese,” “snowclad mountains,” and “immense herds of buffalo.” He wrote about 200 words on the vista stretched out before him and then this: “… after feasting my eyes on this ravishing prospect and resting myself a few minutes I determined to proceed….” Soon after he shoots a buffalo “through the lungs” for meat for the party. He is so involved in watching the buffalo that he forgets to reload. He hears something and turns to discover that he is being stalked by a grizzly bear. He is on the open plain, no trees nearby, away from the river and with an empty rifle. He begins to slowly back up, facing the bear. The bear charges. He runs 80 yards, reloading as he runs. He runs into the river, turns and discovers that the grizzly has remained on the bank. The bear takes off. Lewis is impressed with its speed (I would have been impressed with the fact of my still-beating heart remaining in its chest). He continues his walk, following the path of the bear to the Medicine River. Soon after he is charged by 3 buffalo. He faces them. They stop and retreat. All this time he has been walking on prickly pear, which have thorns over an inch long. He remarks that he stopped to remove them for they had “pierced my feet severely.” After all that, he walks 12 miles back to his party as night falls. Then he writes the journal entry that faithfully records his day. One day.

At the conclusion of Ken Burn’s documentary Lewis and Clark, the writer Dayton Duncan is speaking about Lewis’s suicide; he describes Lewis sitting outside a grimy inn on the Natchez Trace in Tennessee. He was on his way to Washington from St. Louis where he had been serving as the Governor of the Louisiana Territory, a disastrous job for him. After returning from the journey, Lewis, in Duncan’s words, “had disintegrated”.

At the conclusion of Ken Burn’s documentary Lewis and Clark, the writer Dayton Duncan is speaking about Lewis’s suicide; he describes Lewis sitting outside a grimy inn on the Natchez Trace in Tennessee. He was on his way to Washington from St. Louis where he had been serving as the Governor of the Louisiana Territory, a disastrous job for him. After returning from the journey, Lewis, in Duncan’s words, “had disintegrated”.

Duncan’s lower lip begins to quiver as he speculates about Lewis hoping to see Clark, his best friend, his deepest brother in arms and

discovery, at that moment hundreds of miles away, appear on the Trace and take him into his care. I watched Duncan restraining his weeping and thought that is exactly how I feel about his life and his end.

The journey lasted 848 days; 2 years, 4 months, 10 days, from May 14, 1804 to September 23, 1806. Essentially, Lewis began his scientific training on June 23, 1801 when he became President Jefferson’s secretary.

He lived in the White House. He spoke with Jefferson every day. They both had minds equally captivated by blank spots on maps and by science. In Jefferson, he may have found a surrogate father (his father had died crossing a swollen river while trying to return to the army during the Revolution).

From the day he began with Jefferson to the day the Expedition returned to St. Louis totals 1902 days. I calculated the time in days because to me those individual days count more than the years somehow. I want to imagine that Lewis was happiest then, that each day, no matter how miserable the weather, no matter how cold or sick, that each day was a jewel for him. His journals suggest so.

What moves me about Lewis is the image of a great man beset by his own demons in a place devoid of friends — to have come from the Corps of Discovery to St Louis and there be surrounded by creditors, job-seekers, a secretary who undermined his authority, drinking way too much, wrecked by depression, alone except for Seaman, the Newfoundland dog who accompanied him on the Expedition and who was his only loyal companion at this time in his life – it hurts to think of him this way. Lewis loved both open space and movement and the tight focus of the Corps; his choice to become a politician and a bureaucrat contributed to his disaster. He anchored himself in a frontier town, adrift in paperwork, apart from the “brothers” whose identity had become his own.

In Brian Hall’s brilliant novel I Should Be Extremely Happy in Your Company, Hall imagine Lewis, minutes before he shoots himself, twice calling Clark’s name, his companion and dearest friend, the one man who might have been able to save him. Lewis was so alone, the loneliest man I can imagine. He has been one of our admired dead for 202 years; he should also be mourned.